Chalk Talk

I miss seeing my grandkids, Kyla and Logan, ages three and five. I used to visit every week or two to babysit, or just to chat and enjoy their play. Sometimes I catch glimpses of them during weekly Zoom meetings with my two adult daughters, Sara and Josie; Sara, who lives two towns away, is their mom. But our meetings are meant to discuss hard realities, to cheer us up about tough moments we aren’t so eager to share with the little ones. We want them to stay happy, and for the most part they seem to be.

Logan was interviewed by one of his dad’s sisters for a Vice News podcast about homeschooling under shelter-in-place orders. He declared his parents “great” teachers; admitted that he only knew the name “coronavirus,” not what it was; and answered a quick and convincing “nope” to his aunt’s question: “Does the coronavirus make you scared?” That was two days into what at this writing has been a four-week isolation from friends, teachers, anyone besides his sister, mom, and dad.

I was seven years old and in the third grade during the tense weeks of the Cuban Missile Crisis, which didn’t go by that name at the time. Since I’d entered elementary school we’d had regular drop drills, folding ourselves under our desks at the sudden order from our teacher, “Drop!” — to protect ourselves from shattered window glass in the event of an explosion. Remarkably, this didn’t frighten me. Drop drills were no different from the fire drills we practiced almost as often. Fire? Form a line and walk to your assigned section of the playground. No problem. Hydrogen bomb? Tuck yourself into a ball beneath your desk, head and neck covered by your arms. No problem!

Only years later did I understand that the game I played with my best friend on the way home from school that fall, copied from the pair of older girls walking ahead of us, was derived from an international incident. We assumed gruff voices and barked gibberish at each other, calling ourselves Khrushchev and Castro. Mostly we fought over who got to be Khrushchev, somehow intuiting the Soviet leader’s greater power in the perilous standoff.

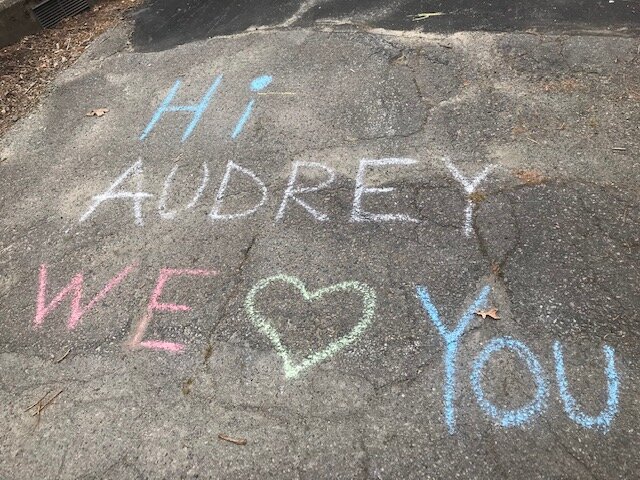

I worry now about kids who can’t work out their fears in play with friends. Walking in my almost deserted neighborhood, I find messages written in colorful sidewalk chalk outside double- and triple-deckers where families live — “Hi Max & Xander Hope you got a good scooter ride in today” “Hello Max I liked the book Will” “Hi Girls Ben + Will + Mason” — and think instruction is the least of what these kids are missing with schoolhouse doors closed.

Farther down the street, high schoolers inscribe messages directed to passersby like me: the now popular slogan adapted from Churchill, “Stay calm, live on!” or simply, “Stay safe!” One afternoon I found a drawing of the local high school signed by Olivia, and wondered whether her affection for the building had grown since the shutdown.

When I was a kid, we only had white chalk, thin sticks that broke easily as we marked out hopscotch squares, or sometimes a four-square court on a broad asphalt driveway, scraping and bloodying our knuckles in the process. I’ve been seeing that too: challenges to leap distances or perform sets of jumping jacks, and what appear to be sidewalk versions of board games like Candyland that anyone walking in the neighborhood can play — “move forward three spaces” “send opponent back 1 space” “you win!” But it’s the personal messages that get me, when I know very well these children have oodles of screen time to communicate virtually (my daughter tells me parents are loosening up on the rules) and “see” each other in Zoom-style classrooms.

Maybe the urge to leave one’s mark, tell a story, on an available surface is atavistic — like painting on the walls of caves. Yes, the rain comes to wash away the chalk, but the kids return to write new messages. It’s the sidewalk that’s permanent: there to bloody your knuckles when you draw or your knees and chin when you fall off your bike. The sidewalk was there before Covid-19, and it’s still here today, as solid as anything might feel to a kid right now.

We’re four weeks in and this morning I read: “Hi Molly Hi Dylan I hope we get to have a play date after this ends.” The chalk artist left no name, only a heart and a cupcake and “we miss you.” Molly or Dylan, or maybe another child scootering by, had paused to sketch a Teddy bear and write back: “I want cupcakes.” Whoever it was spoke for all of us.

Megan Marshall is the winner of the 2014 Pulitzer Prize in Biography for Margaret Fuller. She is also the author of The Peabody Sisters, which won the Francis Parkman Prize, the Mark Lynton History Prize, and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 2006, and of 2017's Elizabeth Bishop: A Miracle for Breakfast. She is the Charles Wesley Emerson College Professor and teaches narrative nonfiction and the art of archival research in the MFA program at Emerson College. Most recently, Megan edited The Blood of San Gennaro by her late partner Scott Harney, published by Arrowsmith Press (2020).