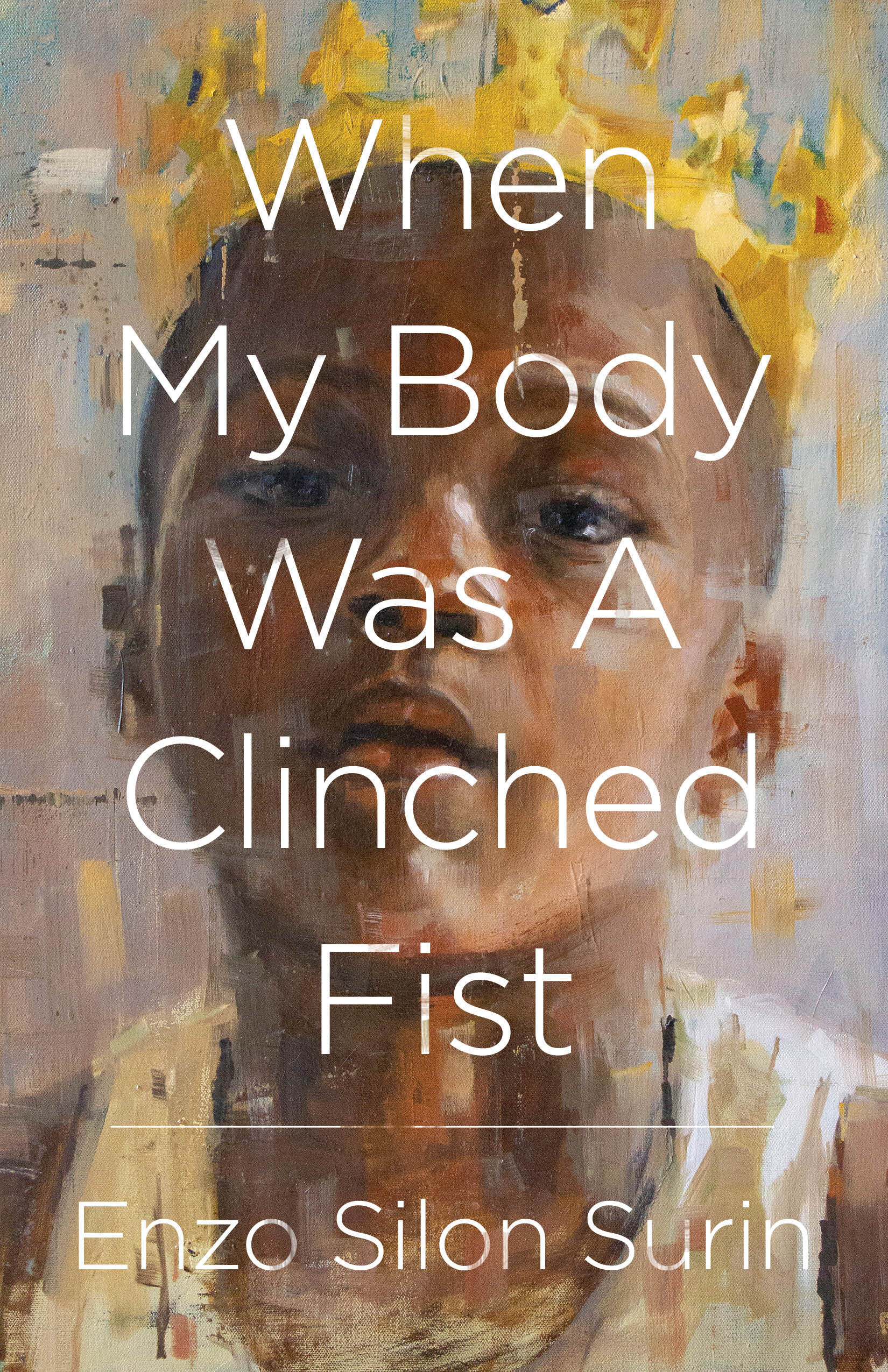

When My Body Was a Clinched Fist

When My Body Was a Clinched Fist, by Enzo Silon Surin

Black Lawrence Press

$16.95

Enzo Silon Surin’s Central Square Press is home, as the website notes, to “Poetry for the Broken Spaces.” The catalogue he edits and publishes includes Afaa Micheal Weaver’s A Hard Summation, Daniel Legros Georges’ Letters from Congo, Lisa Pegram’s Cracked Calabash, and Bonita Lee Penn’s horrifyingly prescient title Every Morning a Foot is Looking for My Neck. Now, Black Lawrence Press has published Surin’s first full-length collection, When My Body Was a Clinched Fist. Surin introduces his book with a quote from Peter A. Levine’s Trauma and Memory: in the case of acute trauma, there are “hardwired emergency responses that call upon our basic survival instincts in the face of a threat. These fixed action patterns include bracing, contracting, retracting, fighting…” From emergency and trauma, Silon fashions a sequence of lyrics that mourn, memorialize, electrify, and ultimately brace a path toward healing.

Looking at a “one-hundred-year-old poplar” with his four-year-old son, Surin reflects:

I was his age when

I experienced my first loss—when my dad left Haiti

to build what he hoped would be better life in New

York City; mom followed a year later…

Surin’s father settled in Jamaica, Queens in the mid-1980s; a decade after the headline “Ford to City: Drop Dead,” the crack epidemic — abetted by poverty and segregation — was eviscerating a neighborhood still suffering from austerity imposed by New York’s near-bankruptcy.

Four years later Leon

caught a beat down from the boys on 164th

street and my body began its first tucking rotation.

…In another four years Frankie

would be stabbed to death.

Rather than serve as a summary introduction, “When the Body Returns as A One-Hundred-Year-Old Fist” is the book’s final poem. Surin has survived to shape a narrative for his son, but only after suffering the jolts of pain and confusion a reader first experiences with him as fragments. In “Letters to A Young Fist,” Surin writes:

Before you sign your name on chalk

outlines, know this: the shape you

mold your hand to hold a gun is

the same as to sway a pen, to cup a yawn

or knot the lace of a doo rag—it’s hard

to ward grief off—to know when.

No one can predict grief’s ambush when a single gesture can fizzle into everyday boredom, rise in eloquence, or explode in death.

In “Banking in Jars,” when Surin learns that his mother was held up after making a withdrawal at an ATM, he thinks for the first time about:

whittling down a high-five

into an eternally sealed conclave

of five finger bandits

Notice what the poet packs into fourteen words: an exuberant greeting forever diminished, locked into a secret council of thieves. What’s stolen is life, trust, and peace as the young man rehearses in the attic, “sweating and gauging/the amount of pressure to an imagined/ temple...” He combs his neighborhood for culprits, “searching for/confessions in faces,” until “almost every face fitting the mold/was a head game.” If Surin’s “sealed” echoes “death’s second self, that seals up all in rest” — and Surin surely risks his life searching for revenge—what follows is hell. Rather than succoring his mother, his secrets isolate him from her: “it’s why she quietly banked her/tears around the house for an entire year.”

Surin’s formal invention matches manner to matter. Hip-hop rhymes and chants through “Elegy for One Sixty-First Street” and “Corners,” showing how style can set a scene. In the sonnet sequence “Letters to a Young Fist,” a series of dramatic actions builds to a devastating final couplet, each poem a facet of the time when “your best friend no longer needs his name.” “Total Recall” and “Anamnesis” — sections of “Pathology of a Clinched Fist” — are simultaneously prose poems, litanies, and concrete poems shaped like a hand. “Pathology…” is one of several poems — scattered throughout the book’s five sections — that share a single title. Along with “Elegy for Frankie” and “When Lead Became a New High,” they enact the recurrence and detonations of traumatic memories.

There’s no safety in a world of fists vs. guns. In “High School English,” Byron is “escorted from the pages,/ambulance siren falling away/through the frost window.” In the poem’s mirror twin, “High’s Cool English,” “We fit ourselves into/small silences, the width of which/depends on where we live.” “Up Against the Wall ‘94” likens the forced intimacy of stop-and-frisk to sexual assault. It’s little wonder that “some nights,” when others might scroll through Facebook for “signs/of life,” Surin searches on Google “for obituaries/of friends estranged, missing or gone.”

Yet the book ends with cautious hope as Surin considers his own journey reflected in the poplar his son says is pointing at him. He responds:

…the only thing one could ask when a hundred-

year-old tree, which, like my body, has survived many

clenched fist seasons, seemingly returning to the same

shape, & greeting the various, abhorrent winters

— this tree “informing our new/definition of optimism” — is, “’did you point back?’”

Central Square Press and Black Lawrence Press steer readers to American voices not always heard above the clamor of crowds. Small independents deserve direct support from readers — instead of one-clicking on Amazon, order these titles directly from the publisher, or from a local bookstore — yes, now.

Joyce Peseroff's fifth book of poems, Know Thyself, was designated a "must read" by the 2016 Massachusetts Book Award. Recent poems and reviews appear or are forthcoming in On the Seawall, Plume, Plume Anthology, and The Massachusetts Review. She directed UMass Boston's MFA Program in its first four years, and currently blogs on writing and literature at joycepeseroff.com