Delayed Flights

Some works of art exert such a powerful gravitational pull they bend reality to their dreams. Italo Calvino´s If On a Winter´s Night a Traveler was one such for me. Reading the novel while standing on a packed Green Line trolley approaching Boston University, I had just reached the part where the “you” reading the novel meets a young woman who has recently read the same novel when a young woman standing a few passengers down muscled her way up and said she’d just read the Calvino and wanted to talk about it. Clearly Calvino had invented her in order to demonstrate how porous was the line between reality and the “vivid, continuous dream” that is fiction.

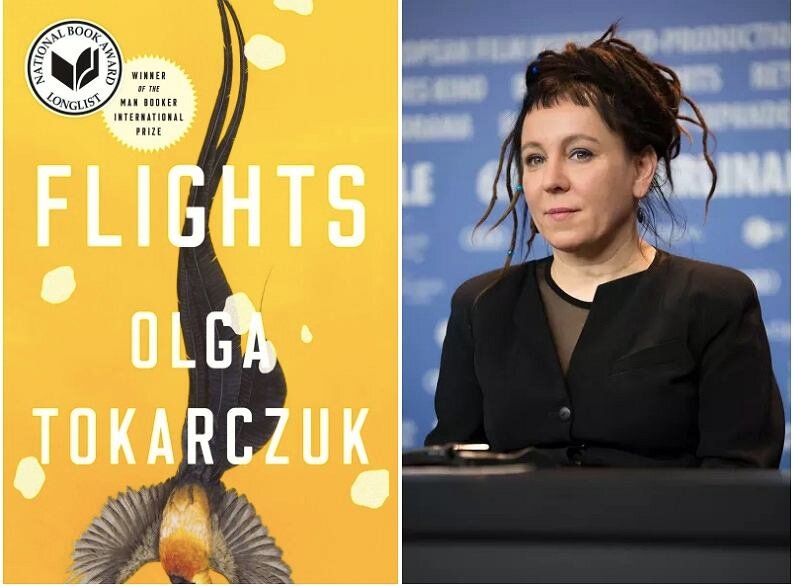

For several days last year the line between reality and fiction was similarly blurred. This time, it was erased by Olga Tokarczuk’s masterpiece, Flights. Returning from a book launch in Lviv, Ukraine to my home in Boston, a series of delayed flights on the Polish airline Lot led to missed connections and mounting frustrations. Every half hour the attendant at the gate in Warsaw’s Chopin Airport would announce the flight had been delayed by “another few minutes.” Grumbling, I would return to reading Tokarczuk’s book. Eventually these minutes grew into hours. Admittedly, the hours flew by, propelled by the updraft of the writer’s prose. At the same time I was painfully aware I had already missed the connecting flight which was to take me from Munich to Logan. This was bad. I had somewhere to be, and now it looked certain I would never get there on time. Things came close to turning ugly when a passage in Tokarczuk’s book abruptly defused them. Confronting an overbooked flight, the novel’s narrator suddenly realizes “I wasn’t in a hurry. I never had any particular place to be at any particular time. Let time watch me, not me it.”

While I definitely had somewhere to be, the consequences of my not being there were hardly grave. What good would raising my blood pressure do anyone, least of all me? Then and there I adjusted my attitude: just watch me, time. You just watch.

“Each of my pilgrimages,” writes Tokarczuk, “aims at another pilgrim.” The word pilgrim is resonant, as technically it describes a traveler to a holy place. While her Flights, masterfully translated by Jennifer Croft, might appear as a paean to travel and the self-delighting dynamism of motion (“my energy derives from movement,” notes Tokarczuk) it is so very much more. Here sincerity is seasoned with slyness and charm, quickly offset by the flashing incisors of truth. Her mosaic of multiple narratives memorializes earthly delights and unearthly yet all too human horrors. A chance encounter at an airport with a stranger inspires this ominous response: “They say you have to sacrifice some living being when you build an airport…to ward off catastrophe.” Episodes chronicling the casual cruelties of animal taxidermy culminate in the horrifying, bizarre, and alas true story of Soliman, an enslaved Nigerian man whose natural gifts enabled him to marry a general´s daughter and eventually elevated him to the post of tutor and chief servant to the Prince of Vienna, as well as making him head of the powerful masonic lodge where he frequently crossed paths with Mozart, among others. At his death he was skinned, stuffed, and turned into an exhibit in the Imperial Natural History Collections. Soliman’s own daughters’ letters to the emperor begging for the return of his body are among the most poignant documents you will ever read.

Oddly enough, the place I had to be was the Brookline Booksmith, for a conversation with none other than Olga, the author herself. I’d met her the previous year in Kyiv through our mutual friend, the extraordinary Ukrainian novelist and public intellectual Oksana Zabuzhko. We had adjourned to a bar after a very long reading. It was a rare treat for me as I no longer drink and tend to avoid bars. We stayed late, lost in an exuberant, multilingual, scrambled conversation about politics and prose. Both women moved fluidly between English, Polish, and Ukrainian. I limped behind. Olga and Oksana articulated their frustration with the expectations created by the traditional English novel, which favors a plot-driven narrative. They defended its Central and Eastern European cousin, which revels in digression and other rhetorical excesses. Olga pointed out what should have been obvious, that the fluidity of borders in Central and Eastern Europe had a lot to do with the spillage or looseness in their fiction, as well as with the often amorphous contours of a book’s characters. Implicit too was the observation that Anglo Saxon fiction has benefited by evolving inside the safety of an island culture. The borders of England (and, for that matter, of Ireland, Australia, Canada, and the US) have not changed much in the last century. Compare this to the many adjustments cartographers have had to make to the outlines of Central and Eastern European nations, beginning a century ago with the resurrection of Poland post-Versailles. All of this reminded me of Orhan Pamuk’s observation that he no longer subscribed to the aesthetic in which he’d been educated, which might be summarized as “the novel as defined by Dickens.” In reality few people have half as much character as the characters in most traditional novels. Other elements in a story, such as landscape, deserve to be elevated as coeval to the human players romping across a page.

The genius of Tokarczuk’s astonishing book is that, while many of these episodes appear (and to a degree are) self-contained, the cumulative force and thematic development lead to moments of exhilarating revelation often delivered in the span of a few sentences. The theme of holiness recurs in various guises: “He who rules the world has no power over movement, and knows that our body in motion is holy, and only then can you escape him, once you’ve taken off…That is why tyrants of all stripes…have such deep-seated hatred for nomads — this is why they persecute the Gypsies and the Jews, and why they force all free people to settle, assigning them the addresses that serve as their sentences. What they want is to create a frozen order…to build a big machine where every creature will be forced to take its place and carry out false actions. Institutions and offices, stamps, newsletters, a hierarchy, and ranks, degrees, applications and rejections, passports, numbers, cards, election results, sales and amassing points, collecting….Move. Get going. Blessed is he who leaves.”

I suspect no living being was sacrificed during the building of Warsaw’s Chopin Airport, for which I am grateful. My delayed flights were a small price to pay for the Poles’ failure to honor the necessary rituals. I finally landed in Boston, mere hours too late to make it to the bookstore. In any case, I managed to catch up with Olga and Jennifer the next morning as they were about to board the Amtrak train to New York — two holy bodies in perpetual motion.

“It is better to stay silent or to say something better than silence,” said the austere Pythagoras. To which Tokarczuk shouts: Speak! Speak! “Because the strongest muscle in the body is the tongue.” And who knows what the tongue set free might say, what revelations it might offer.

Like a tree, a great work of art doesn’t try deliberately to help you, but like a tree, by its nature, it is what enables us to breathe.

Askold Melnyczuk’s book of stories, The Man Who Would Not Bow, appeared in 2021. His four novels have variously been named a New York Times Notable, an LA Times Best Books of the Year, and an Editor’s Choice by the American Library Association’s Booklist. He is also co-editor of From Three Worlds, an anthology of Ukrainian Writers. His published translations include work by Oksana Zabuzhko, Marjana Savka, Bohdan Boychuk, Ivan Drach, and Skovoroda. His shorter work, including essays, stories, and reviews, have appeared in The Paris Review, The New York Times, The Missouri Review, The Times Literary Supplement (London), The Los Angeles Times, The Harvard Review and elsewhere. He’s received a three-year Lila Wallace-Readers’ Digest Award in Fiction, the McGinnis Award in Fiction, and the George Garret Award from AWP for his contributions to the literary community. As founding editor of Agni he received PEN’s Magid Award for creating “one of America’s, and the world’s, leading literary journals.” Founding editor of Arrowsmith Press, he has taught at Boston University, Harvard, Bennington College and currently teaches at the University of Massachusetts Boston. Most recently he has been organizing readings in support of writers in Ukraine, as well as interviewing writers for his For the Record series which appears online at Agni Online (https://agnionline.bu.edu/blog/for-the-record-conversations- with-ukrainian-writers/), as well as on Arrowsmith Press’s website.