Report From Dimension Zero

In the world before the coronavirus, I planned a research trip to Rome for a long-delayed short book on Bernini’s Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi. I browsed flights and hotels. But the next morning’s New York Times ran a photo of N95 masks in the Colosseum.

I then imagined flying home to Kentucky to write about the state’s thirteen remaining covered bridges. Rabelais would list them here, I now do so. Beech Fork Bridge, Mooresville, spanning Beech Fork of Chaplin River; Bennetts Mill Bridge, Beechy, over Tygarts Creek; Cabin Creek Bridge, Fearsville; Colville Bridge, Ruddels Mills, across Hinkston Creek; Dover Bridge, over Lee Creek; Goddard Bridge, across Sand Lick Creek; Hillsboro Bridge, Grange City, over Fox Creek; Johnson Creek Bridge, Alhambra; Oldtown Bridge, across the Little Sandy River; Ringos Mills Bridge, also over Fox Creek; Switzer Bridge, across North Elkhorn Creek; Valley Pike Bridge, Maysville, over Lee Creek; and Walcott Bridge, Woolcott, across Locust Creek. Doesn’t that sound like a sweet little book? — but by the sixth of March, Kentucky too had declared a state of emergency.

My sometime collaborator, the writer Mike Nagel, emails me from Houston: “Hope you’re well, John. Personally, I’m going out of my mind.” But I am going into my mind. This is what I have found there. The real self and the ego-ideal, the redneck from Fern Creek who wanted to see Rome. He reads through our pandemic at two extremes. On the one hand, Rabelais, a free and easy carnival that delights in and celebrates the dirty pleasures of our open bodies. On the other hand, Jack “King” Kirby’s 1974 comic book OMAC, the one-man army corps, the man with a hundred thousand foes, an antiseptic persecution fantasy.

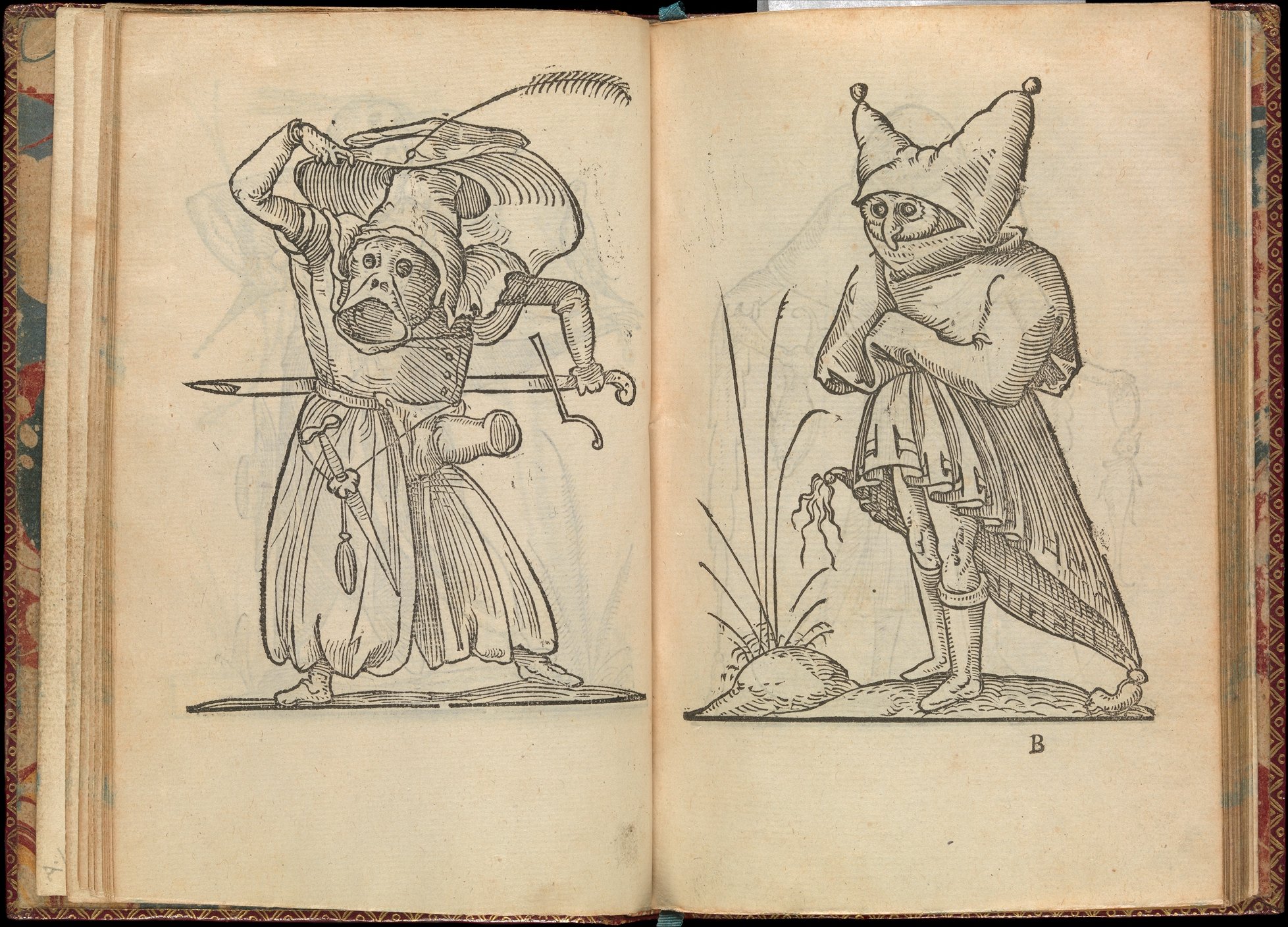

The ego-ideal reads Rabelais. Ahab’s been to college, as well as ‘mong the cannibals. The ego-ideal went to a big state school. Rabelais is the poet of the open body, not quarantine, neither locked down nor locked in, not pandemic, not panic. Instead, Panurge and Pantagruel. At this moment when you must not touch others, and must not touch your own face because the virus might enter one of your mucous membranes, Rabelais is the master celebrant of our apertures, always drinking, eating, shitting, fucking, pissing, and vomiting. Gargantua is a positive Leviathan, not the famous punitive-authoritarian super-ego of Hobbes, but a joyful, giant composite character, a whole country, an entire people. Here comes everybody.

But the boy from Fern Creek reads comic books he can buy for a dime at local yard sales. Here comes no other body. There is a single body, the One-Man-Army-Corps, an isolated body that, for now, must constitute an entire social world, as in the management expression the task expands to fill the available space. “Can one man do the job of thousands?” It’s a fantasy of no dependence, no interdependence. (Jim Grauerholz, longtime boyfriend of Burroughs, said “William would make a good prisoner. I mean, in solitary confinement.” But that solitude-fantasy required a lot of cooperation for its upkeep, and Grauerholz was its chief administrator — or warden.)

OMAC would stand alone against the rest of the world, if there were any “the rest of the world,” but only OMAC, also known as Buddy Blank, is real. The factory where Buddy works manufactures “pseudo-people.” OMAC’s first mission is to destroy them.

There’s nothing mysterious about fantasies like this. As David Mamet writes, “the infantile power fantasy — the infant, denied the breast, is deprived and wants to kill the offending world.” We were all infants, and we all still are. And now we are denied the breast of our world.

I no longer feel my neighbors enough to believe in their reality. They all say the same words, they read the same newspapers, I am not a fool, I have a good memory, I read the same papers and can identify the source materials of their remarks. Panicked, they have collapsed into a single dense Krugman-Kristof repeating-machine. They are pseudo-people. Caligula said, “If all of Rome had one neck, I would slit it,” — but it does. The country has become a reverse-hydra. It has thousands of bodies and a single mouth.

At first I was bored, Christ, Jesus, bored, and I asked, Don’t these people have any thoughts in their heads? But the answer is No. Thoughts come from many valid sources, some people’s thoughts come from outside them. No wonder, then, if they never could mind their own business, because they didn’t have any. Now they choke on the vacuum at the center of their lives. There is a vacuum at the center of my life, too. There is a vacuum at the center of life itself. “God made everything out of nothing,” said Valéry, “but the nothingness still shows through.”

There is no solution, the solution is no-solution, the ocean is the ultimate solution, the solution is to drown, take a big gulp, amor vacui. If you can’t be with the one you love, love that you aren’t with the one you love. Lack is the necessary ground of desire, and desire leads to creation, to hallucinating the missing object, to rebuilding the lost object of desire. God doesn’t know anything, God creates everything. The earth was without form, and void. Shorn of my world, I create a world. I do not go out of my mind, I go into my mind.

But the long-held aim of our obesogenic culture has been to use constant presence to annihilate lack, to encourage the infant with its oral greed. Infants in seeming adult forms call me, screaming, wishing to outsource their panic to me, screaming. What we miss about social life, if we knew it, is projecting our disowned and unwanted feelings into each other. We miss shitting on each other while pretending it’s an Easter egg.

I hang up the phone. I cut the cord.

I can’t save other people. I can’t save them from me.

J. D. Daniels is the winner of a 2016 Whiting Writers’ Award and The Paris Review’s 2013 Terry Southern Prize. His debut book The Correspondence (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux) was published in 2017. His work has appeared in Esquire, The Paris Review, n+1, Agni, Oxford American, Los Angeles Review of Books and elsewhere, including The Best American Essays and The Best American Travel Writing.