Dissolving Boundaries

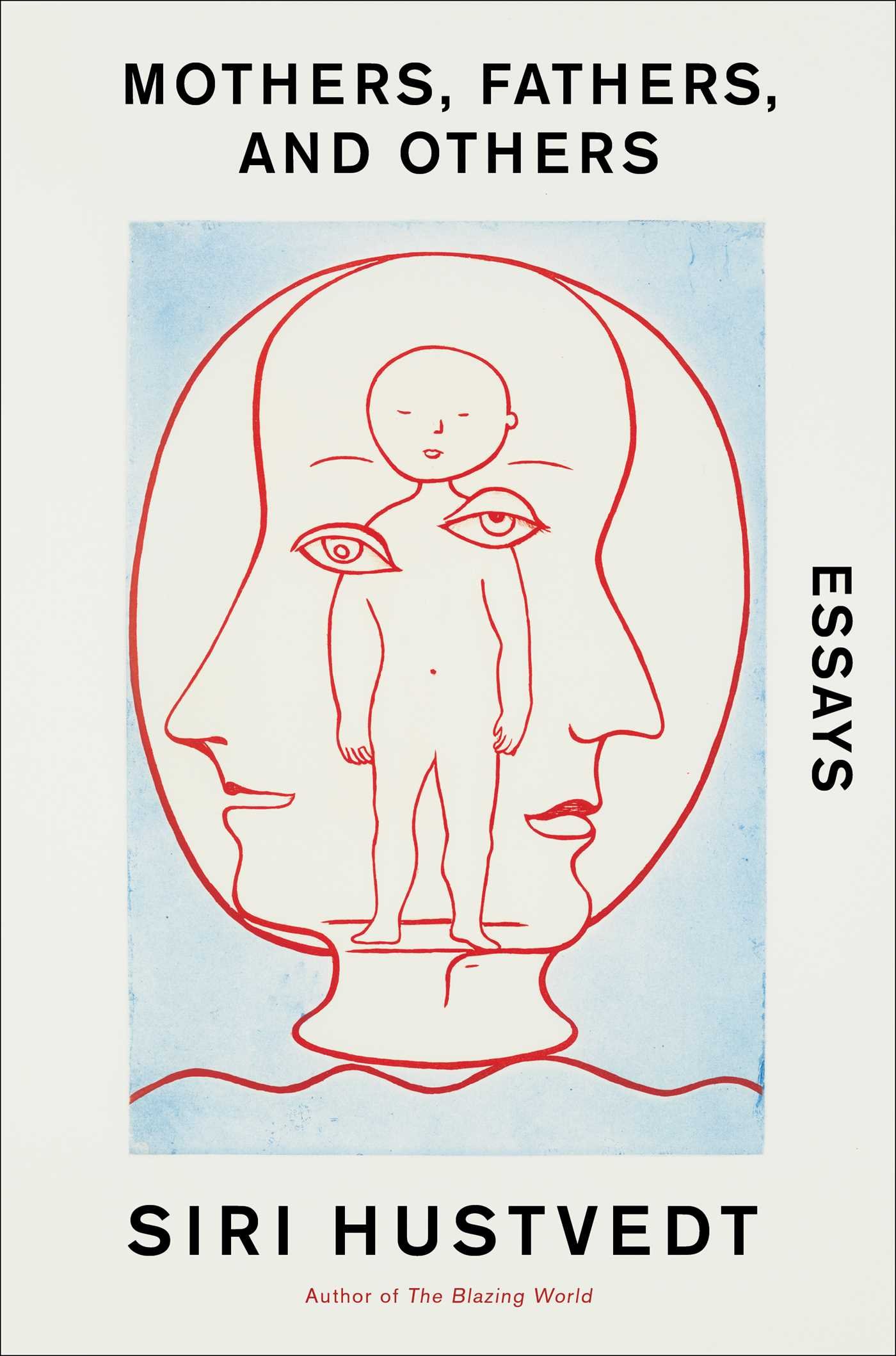

Mothers, Fathers, and Others

Essays by Siri Hustvedt

Simon & Schuster, 2021

“We are all, to one degree or another made of what we call ‘memory,’ not only the bits and pieces of time visible to us in pictures that have hardened with our repeated stories, but also the memories we embody but don’t understand—” p. 9

If memory is an imprint of the past, imagination shapes the future. Envision a number line going in two directions. The narrative artist sits in the middle at zero. In making a narrative, she goes backward via memory, and forward via imagination. Through narrative she connects to a reader. She is both everyone she has ever met and read and everyone who will read her. No matter her topic, she will often be read as a writer of the body, the earthy, the domestic, while a male author will often be read as an intellectual. Hustvedt writes that she has been the object of this shallow mischaracterization when interviewed with her husband, the writer, Paul Auster.

I do question whether to cite Hustvedt’s famous husband at all. Are the sexist distinctions she wishes to blur and eviscerate undermined by Auster’s appearance in my first paragraph? Yet his eruption into this text and hers is a symptom of living in a culture steeped in a patriarchal hierarchy.

Hustevdt, who lectures about narrative psychiatry, notes that “novel emotion” creates lasting memory. Novel emotion also often incites narrative, thus a novel is called a novel. This book begins with two passionate essays, the first about the author’s grandmother, and the second about her mother. Hustvedt’s bond with these matriarchs, more than being the child of her professor father, begets her life as a thinker. Her intense closeness with her mother in later life, as well as her mother’s gentle admonition to Hustvedt’s teenage self, “Don’t do anything you don’t really want to do,” made “want” central and allowed Hustvedt’s own desire as a guiding principle of her life. Being mothered by this woman in this way begat Hustvedt the artist and intellectual, which begat Hustvedt’s connection with the readers of the thirty languages into which her work is translated. In this way, a collective mind forms around shared culture.

These essays are “personal” only in that some facts of her life are shared honestly. Intellectual honesty requires a blurring of genre; the essays are also literary, political, psychological, and scientific. Hustvedt, by acknowledging her own experiences of love, obliterates the dichotomy—deeply embedded in Western thought and the structurally misogynist hierarchies our culture springs from— between emotion and intellect, body and mind. She writes of her own child as an infant. “And yet, I loved stroking her bald head, looking into her enigmatic little face, watching her stare back at me—”. The words “And yet” are significant. She seems to say, I am a thinker, but/and the body in love is formative. The constructed nature of this boundary—an intellectual can’t care for an infant—is damaging. These borders have served to limit women’s experience throughout history and to omit representations of their experience. She points out that representations of birth are rare in Western art despite the fact that everyone is born to a mother.

Another cultural border allocates rage as the province of men. “Kavanuagh…rages with tears..” While Blasey Ford, “testifies in a soft, calm, ladylike voice/…”. Hustvedt does not rage in this book. She proceeds with emotion and logic, facts and imaginative synthesis while leaping over and braiding academic borders. The wealth of Hustvedt’s intellectual trespassing permeates this book as if to say, the wide, wide world begat my parents, my parents physically and culturally begat me, and I gave birth to one child and sixteen books.

The author of seven novels, she asserts that novels in their creation of characters, build our capacity to empathize by imagining the other. She notes our most recent president never reads a book, while Obama makes lists of his yearly top tens by category. The reader is one who crosses borders and thus cares. Yet the myth of good mothers versus bad, the mind and the body, intellect versus emotion, race, places for men and those for women are the myths that gird our cultural landscape and the ones from which all our stories spring. They work to maintain control of hierarchies and as such, create a structural misogyny that shapes our lives.

Hustvedt references her own experience of misogyny, but mercifully veers away from complaint or confession and couches her experience in the larger, more damaging experiences of others. (For example, trans people who reject the gender binary are punished, even murdered at alarming rates. Black women may experience a double and woven punishment of misogyny and racism together.) She is aware of her relative good fortune as a white woman of means. Nonetheless, it's remarkable how many obstacles she has faced, and furthermore how prolifically Hustvedt has achieved in a world that would rather she didn’t. Hustvedt has defied sexist expectations, stemming first from her own father, a professor who said of her dissertation, “It doesn’t read like a dissertation,” and the several professors who failed to mentor her. One, notably a woman and self- proclaimed feminist, said, “What are you doing in graduate school? You look like Grace Kelly.” Hustvedt earnestly asks the reader, “What did my looks have to do with it?” in some ways skirting the issue, not of sexism within academia, which is well known, but of one aspect of her reality, the complicated fact of her (culturally sanctioned) beauty. If literature itself is dialogic, so too are all our human interactions. We can imagine what her looks had to do with it.

Again, I admit, I considered deleting a reference to the author’s looks. They are besides the point, and I would never comment on Paul Auster’s fine Greek profile or soulful eyes. The Grace Kelly remark is deeply hurtful: I can’t see you. Your work doesn’t matter. It can’t matter because you have the other currency, the one that women and men in our culture ascribe to women. The one that matters. I leave the reference in because it is Hustvedt’s own. She is in a sense telling the reader: I looked like a movie star and so I didn’t get the respect I deserved. What would it mean to write that? I do see potential in the book for exploring notions of “beauty” and her own as a facet of the misogynist landscape she inhabits.

The cultural phenomena that was the last presidency both exemplified our structural hierarchies of misogyny and galvanized a new feminist consciousness around sexism in America. Time’s Up. And yet, time is clearly not up. A man accused of no less than twenty-five allegations of sexual assault, including rape, occupied the most powerful position in the world.

In her essay “Notes from the Plague” Hustvedt illuminates a clear example of dissolving boundaries: Covid. Borders of body and nation are ravaged by infection. The virus doesn’t care where the lines are drawn. Furthermore, she writes, the body is always borderless as our microbiome harbors billions of organisms. The whole world experiences the shared misery of isolation, broken economies and death. So, too, there are smaller collectives of consciousness; Hustvedt writes of the uncanny telepathy she and her husband experience after thirty-six years together. “Feelings spread like yawns.” The mind of any person is not simply their own, nor is the body. Art can further our connections and forge cultural affinities across otherwise disparate minds.

Hustvedt is a product of the social hierarchies that she excoriates. In pointing out the misogyny of ancient Greek thinkers she acknowledges the way Plato and Aristotle have shaped her as a thinker. As women we are embedded in the shadow of the structure that oppresses us, even as it erases us from the picture. Hustvedt describes the stupefying experience of being invited to be interviewed about her book and then being asked nothing about her book by the male interlocutor. Maintaining a gender boundary, often means control and an absurd erasure. These omissions matter.

These essays fill in the blank spots. “When we remember or imagine, we miraculously lift ourselves out of our bodies and move in spaces that are not right in front of our eyes but somewhere else.” It is this disembodied travel of the writer and reader (or artist and viewer), and the ability to love a person or a work of art, that dissolves boundaries. In grieving her mother, Hustvedt wonders how her mother can be nowhere. Maybe death is the only true escape from our avid, and often ridiculous classifications and boundaries. Misogyny itself is, she writes, “a strange hate.” In answer to it, Hustvedt conjures her mother in these pages. Her mother is not nowhere, she’s everywhere.

Thea Goodman is the author of a novel The Sunshine When She’s Gone (Henry Holt, 2013) a book about a marital crisis that ensues upon the birth of a first child. Her short story, “Evidence,” the title story of a collection in-progress, was chosen by The New York Public Library for Stories on The MTA, a Digital Archive, 2019. She’s published short fiction, essays, and poems in The New England Review, Catapult, The Rumpus, Columbia, The Penn Review, Other Voices, The Huffington Post and The Coachella Review, among other venues, and won a Pushcart Prize Special Mention, The Columbia Fiction Award and fellowships at Yaddo and The Ragdale Foundation. She was a visiting faculty member teaching creative Writing at The University of Chicago between 2016-2019 and is currently at work on a new novel.