An Ethos of Attunement: Ruxandra Novac Among Objects

A buzzword of the first post-Cold War decade, “transition” held out the promise of a fresh start for most countries of the former Eastern Bloc and, as such, seemed preferable to the inanely retweeted “end of history.”¹ But the quantum leap out of pre-1990 economic, social, and cultural modes such as centralized planning, single-party rule, and politically Aesopian postmodernism did not quite happen. Repeatedly botched “shock therapies” slowed the rebound down to an agonizing crawl all over the East, and before long, the euphorically advertised narrative of smooth progress toward a prosperous society would ring hollow in the face of bruising realities: the implosion or hasty liquidation of manufacturing industries, the collapse of national currencies, skyrocketing inflation, surreal corruption, and the quiet return of apparatchiks and secret-police cadres as “entrepreneurs” and nouveaux riches. Glaring disparities between recently minted categories of “winners” and “losers” went hand in glove with dire poverty, homelessness, crime, an exodus to the affluent West, and a culture of cynicism that made empathy, dedication to the common good, and hope look foolhardy. These were some of the basic ingredients of what would come to be referred to as postcommunist precarity. To many, this was late twentieth-century reality, even though, in and of itself, it was not entirely new; to be sure, there had been plenty of venality, indigence, and scarcity under the obscenely overfed communist oligarchies of Central and Eastern Europe, when people scraped along amid all manner of shortages and indignities. New was writers’ freedom to tackle the transition hardships openly by availing themselves of the unprecedented degree of permissiveness publishing houses, magazines, and the other media began to enjoy after 1989.

It was in this post-censorship, if increasingly neoliberal, context that the “barbarian” and self-declared “anarchist” poets of the 1990s and the first years of the third millennium in countries like Poland and Romania took on the gaps and disjunctions between what was painfully “real” and the fictions, accounts, and rationales prone to sugarcoat, downplay, aestheticize, or explain it away. In Romania, the young, “postmillennial” writers, primarily the poets who set out to canvas the social geometry of this systemic hypocrisy, zeroed in quickly on the cracks and “fractures” between concrete actuality and how one represented it or how one presented oneself in relation to it, especially if one wrote about it. Befittingly enough, these authors called themselves “Fracturists” and their works “fractures.” They did so largely in the wake of the publication of the 1998 “Fracturist Manifesto” and its “addenda” and sequels by Marius Ianuş, Dumitru Crudu, and Ionuţ Chiva.²

As incendiary as the previous, the “definitive” version of the Fracturist platform bears many of the hallmarks of post-postmodern neo-avant-gardes from around the early twenty-first-century world, particularly the United States. Prominent within this brutal, vehemently anti-bourgeois and anti-capitalist aesthetic of disenchantment is a deep dissatisfaction with Romanian postmodernism’s intertextually allusive and ironically detached beating around the bush of the terrible socioeconomic mess of the 1980s and 1990s. The postmillennials turn away, accordingly, from postmodern “constructionism” and its literary-historical, conceptual, “correlational,” and, insisted Ianuş, “anthropocentric”³ mediation of being, to a more straightforward, politically and linguistically pugnacious realism, to “authenticity,” “sincerity,” “autobiographism,” and more generally to a poetry billed, in a similar vein, as an uncompromised showcase of the poetic ego’s “strictly personal [. . .] reactions.”⁴

The aporia, the “fracture” rupturing this Fracturist ars poetica itself, is unmistakable not only in the original manifesto but also in its avatars.⁵ Thus, Crudu thinks that “objects brought into focus need to play second fiddle” to how poets attest to them; “authenticity can solely exist,” he contends, “at the level of [our] reactions” to objects.⁶ But Fracturists such as Ianuş and Crudu also reject the bookish, intensely subjective packaging (“labeling”) of reality and, in the same breath, a poetry orbiting and catering to the human.⁷ Consequently, Fracturism is torn between, on one side, an angry poetic phenomenology rooted in a Kantian ontology centered on the human subject, and on the other, a “post-correlationist” realism that deems this subject just one object among myriad others in an existentially “democratic,” nonhierarchical thing-world.⁸ Notably, this world no longer warrants us, humans, any prerogatives, epistemologically or otherwise. In it, crickets, subway ticket stubs, dust devils, and acacia thorns do not exist courtesy of “our” allegedly unique ability to acknowledge and rationalize their existence.⁹ Each and every one of them merely is—no more and no less. They are ontologically “strong,” not byproducts of the perceptions and cogitations Immanuel Kant’s transcendental categories are said to enable in “us.” Instead, all those critters, artifacts, and what have you “just are there,” whether “we” are around or not. Not only that, but their being there is the a priori of any possible dealings we may have with them, and so everything follows from their ontological “thereness.” Anything we may say or do about them, any revelations, emotions, or decisions concerning them, any semantic, psychological, political, or ethical claims we may make with respect to them ought to be premised on their “strong ontology”—on an “ontology of equal-footing objects,” that is.¹ᴼ

This de-anthropocentered or “flat” ontology affords and, for all intents and purposes, prompts a “horizontal,” more discerning, and poetically illuminating approach to world ecologies, to the webs of intertwined things around us, people—human people, Timothy Morton might quip.¹¹ The proviso here is that “approach” must be taken in its basic sense of treading over a material geography of existents, toward others—other objects existing as we ourselves do, on the same plane of being. The gaze, “ours,” historically peering down at them from the top of the classical onto-theological ladder, is inherently violent and thereby impervious to otherness. But the level-ground trekking is, and tells, another story. This seemingly aimless “destinerrance,” as Jacques Derrida might say, or better yet, its object-oriented cousin “veering,” to which Morton also alerts us, is “always already,” as the cliché goes, to cross over to the other side.¹² As kinetic as it is gnoseological, the veering approach involves stepping across all kinds of barriers to make contact, touch, and feel others, while they do the same so as to share our spaces, bodies, and lives. Inching closer and getting through whatever lies between us and them, they bring about a sensuous de-limitation of the human, giving it a touch-like, con-tactile access to the world-systems of thingness—not necessarily a full grasping or understanding, an “elucidation” of others in the animate and inanimate kingdoms, but a way of being with them, an ethical form of relating and of bearing witness to it.

This form, I would argue, is how Ruxandra Novac, the most important Romanian poet to arise in the third millennium, has negotiated the above-mentioned Fracturist contradiction and the quicksands of aesthetic, existential, and political inconsistencies swirling around it. A writer connected in the beginning, albeit rather loosely, with the postmodern “Braşov School” of poets, prose authors, and theorists such as Alexandru Muşina and Andrei Bodiu, Novac has been associated with Fracturism along with Ianuş, its one-time leader, and his comrades in arms Ștefan Baştovoi, Alexandru Vakulovski, Răzvan Ţupa, Ioana Baetica, Adrian Schiop, and Bogdan Perdivară, to name but a few. As has been suggested—correctly, to my mind—this association, too, has been imperfect. Nor is today’s Fracturism what it was when its manifesto first came out. Since then, the high-profile Fracturists, Ianuş included, have moved on, some of them in conservative and even Far-Right, Orthodox Christian, and patently bigoted directions, reenacting the incongruities and involutions for which European avant-gardes have been known throughout their convulsive history.

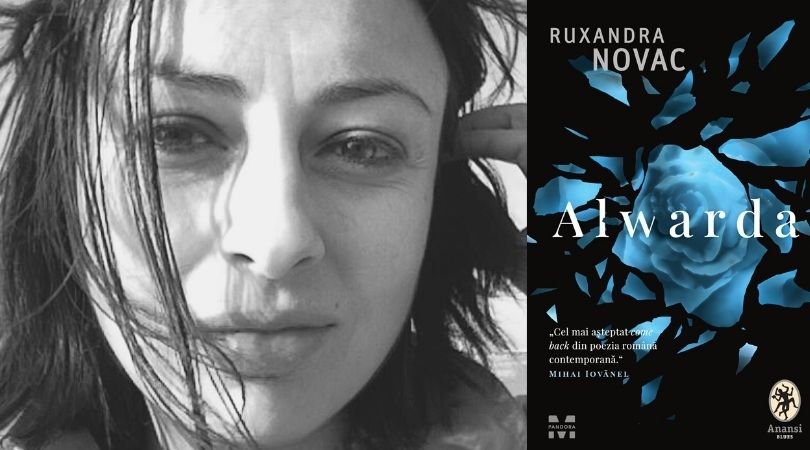

Novac has evolved as well, but her trajectory is saliently different from Ianuş’s. It maps over time, from the widely influential 2003 poetry volume ecograffiti. poeme pedagogice. steaguri pe turnuri¹³ to the 2020 collection of poems Alwarda, the progression, if not the outright progress, from the more static and local, geoculturally bounded, prevailingly anthropocentric, and aggressively self-centered egological aesthetics of her early Fracturist texts to an ecological, “worlded,” and more cosmopolitan approach, which, as I have indicated, itself implies a dynamic ethos, a journey of its own.¹⁴ If Alwarda, “the most impatiently awaited comeback in contemporary Romanian poetry,”¹⁵ is “radically new,” then, as I propose in these pages, the novelty stems from this change of course. On the other hand, the notion that the second book makes a clean break with the first is something of a stretch.¹⁶ It would be fair to say, in fact, that the 2003 volume is already sowing the seeds of this shift—witness the title itself, which originally began with, and would eventually be cut down to, a single noun, “ecograffiti.”

The word is intriguing, as Alwarda will be years later. Likely, the first thing it brings to mind is its quasi homophone, the medical term echography, complete with allusions to the screening, sounding, and “writing” of corporeality, specifically to the inwardness of Fracturism’s ego-scopic écriture, rather than to ecologically minded street art, although Novac’s 2003 poems brazenly tag Bucharest’s cheerless cityscapes. Yet the title also hints at a nascent fusion and poetic “synonymizing” of natural and artificial systems of inscription, “my” body and other bodies, human and nonhuman, “in” and “out,” and so on. At this stage, however, her liminal and taxonomic imagery riffs extensively on the fracture master trope and is harnessed to an in-your-face, verbally abrasive politics of disconnect. Divides, distinctions, and categories are in place here, as they will always be in Novac, but they stand out even though, in anticipation of processes Alwarda will boost, they are already somewhat porous and wobbly. Unable to keep reality at bay, they let the backdrop of a capital city that “looks like a dead rat” seep into private domains, and so “[s]lowly the room is filling up with water. / Slowly it is turning into a live swamp. / Slowly my sad self is crawling toward the TV screen / and nests in there as in a live hole. / Among bulbs and circuit boards as in a live hole. / It opens up in there sadder than an elephants’ boneyard, / sadder than the carcass of a charred train engine, / as a cat’s breastbone on red clay, in sunlight” (“as in a little fence, as in a metallic lacework” [16]).¹⁷ This imagery, this residual Imagism actually, has been described as Neoexpressionist, and for good reason too. It is visually striking, descriptive yet enigmatically so, stringing together, without an immediately apparent logic, sharply contrasting metaphors of life and death in a fitful syntax of arresting non-sequiturs, disjoined sentences, elliptical phrases, scant punctuation, and faux repetitions—as many reiterations that do not build up toward any resolution, conclusion, or crowning realization.

Far from rehashing pre-postmodern modernism’s neoclassical aspirations to order, synthesis, and self-fashioning, this post-postmodernism shores against the self’s ruins neither Bucharest’s crumbling, communist-era projects nor their presumed aesthetic vindication, the poem’s own textual fragments. This poetry is not “edifying” in any sense imaginable. Or, to rehearse my earlier comment on Fracturist aesthetics, the edification is antiphrastically disenchanting, a sobering up of the self, which is either steeped in the “sulphureous desert” where a “failed adolescence” has already wound up, as in a later poem (54), or goes down in the swampy water that, as in the excerpt quoted above, floods the apartment of the poet to disabuse her of any personal and sociopolitical illusions. “Here,” writes Novac in “r. w. f.,” ecograffiti’s opening poem, “there is room / neither for pity nor for freedom nor for yearning / everything is clamping down is pulling you lower and lower / all the way to the end’s end / everything is a howl / a brownish water / that washes over me again and again / from which I drink again and again / while my women make money” (7).

“Yearning” is one way of rendering Novac’s word dor, a much-ballyhooed trademark of Romanian Kultur-Morphologie. The noun denotes longing for something or somebody, as well as pain, suffering, and sorrow, in accord with its etymon, the “vulgar” Latin dolum, which is related to dolor (pain, grief) and became deuil (bereavement, mourning) in French. This semantic profusion is the shaky foundation on which post-Romantic Romanian critics and philosophers of culture have developed an entire mystique of national identity. There is little question, though, that Novac—a bona-fide anti-Romantic, like most avant-gardists in Romania and elsewhere—presses the term into service ironically. The “characteristically Romanian” feeling, along with the rest of the “empty words” (cuvinte frumoase) rattled off for “thousands of years,” such as the poem’s own “pity” (milă) and “freedom” (libertate), are, Novac writes, nothing but “food for the dead,” much like “Great Men’s yellowish fat” (7). ecograffiti does invoke some of these historical figures, yet the mentions are absurd—they make little sense in their respective contexts—when they are not irreverent or ironic.

Bordering on snappy sarcasm, the irony here is not the well-too-known, jocular, and elaborated postmodern ploy. Granted, there are echoes of postmodern Romanian authors in ecograffiti—by the early 2000s, one of Romanian literature’s contemporary classics—but such resonances are faint and few and far between. Most of them ripple furtively across the urban vignettes, wrinkling up the metropolitan vistas into literarily “thick” loci redolent of Mircea Cărtărescu, Florin Iaru, Traian T. Coşovei, and their earlier forays into a spectacular Bucharest of “electric snow” (the title of Coşovei’s debut book), flickering neon signs, blinding headlights, and glistening, if empty, display windows. In hindsight, however, the 1980s poetic flâneurs’ close captioning of technicolor Socialism sounds less realistic, less authentic, and less subversive than it originally appeared to publics, critics, and—nota bene—censors alike. In fact, postmillennial readers and writers in Romania and elsewhere find it rather contrived, excessively quotational, flippant but stifled by stylistic obliqueness, cluttered by ornament, and calling out to the Beat masters in ways that now come off as politically defanged and gratuitously “ludic.”¹⁸ At least retrospectively, Cărtărescu and most of the members of the “Monday Literary Circle” (Cenaclul de luni) led by Nicolae Manolescu, Romania’s most influential post-World War II critic, seemed to enjoy themselves. Because of that, the most significant poetic presence of the 1980s in ecograffiti is Mariana Marin.¹⁹

Marin’s Bucharest was anything but fun. In 1981, in her first book of poetry, Un război de o sută de ani (A Hundred Years War), Marin uncovered behind the shiny façade of funhouse Bucharest the prison-house where the regime was depriving the city residents of basic rights such as freedom of movement. “You’ve got no place to go. Reader, nobody is traveling,” she disclosed in one of the volume’s more overtly “political poem[s.]”²ᴼ The text, however, would go places, and some of them are in ecograffiti. “[W]e,” Novac echoes Marin, “are unknown animals in underground car parks, / ready for a perfect crime / we have not come out / never will / if we are afraid we curse / if we open our arms / they drop hearts and empty bottles” (18). Since “here is better than anywhere else,” as Novac comments sarcastically, “we will never come out, / will never leave, / here is better than anywhere else / one cannot leave here” (18-19). In Novac’s Bucharest, one is irredeemably stuck:

one cannot leave here

we are the last ones this is our world

and it has been just like this forever

from the heater to the window slowly as in a movie

from the ends of the earth warmed up by alcohol

the working-class guy comes up to us

to teach us which is which and why

and we know he is right

we left behind in dreary rail stations all we could have left

now we will leave our own head

wrapped up for the future in newspapers

in the night’s delirium the moths

feel up their veins

somehow surprised to find them

in their places warm and soft

in the summer night’s delirium the moths come out

and tear asunder anything they come across

their eyes reddened by smoke and joy

for us are meant all these things as long as the blood is warm

for us are the latest newborns in a rotten and heavy city

of rotten and heavy nights” (28).

The nondescript parking lots, the dank rooms (their “walls covered in sweat” [36]), the poor, and the junkies have turned the onetime charming “Paris of the Balkans”’ into an allegory of affective and material precarity spawning germanely touch-and-go lifestyles (“as in a permanent state of emergency or / from hand to mouth” [38]), with people failing to keep afloat on the “piss sluice” that “sweeps [them] away” (39) (“a liquid getting everywhere was getting into my mouth” [20]). A testimony to the culture of destitution, postmillennial Romanian literature and art, including internationally acclaimed film, have largely evolved a whole style of their own to limn the “rotten city” and the abject minutia of transition broadly. This is a postcommunist neorealism of sorts that has been dubbed mizerabilism. The term recalls less English “miserabilism,” which foregrounds the psychological aspects of “misery,” and more the latter’s social and economic meanings, which Romance languages such as Romanian tend to play up (as did Victor Hugo in his novel title).

Arguably, important post-2000 Romanian prose writers and poets like Adrian Schiop, Petre Barbu, Dan Sociu, and Elena Vlădăreanu are keener on the seediness and frailty of life after communism than Novac. It is not that her ecograffiti cannot be mercilessly graphic, though; they can be and occasionally are. But, as in Lavinia Branişte’s fiction, there always seems to be a bigger point to this no-holds-barred, unscreened realism and its appositely unfiltered verbalization. At this stage in Novac’s career, the point has to do, I think, not so much with brutalist and coarse detail per se as with the poetic self’s reactions to it and, more broadly, with an aesthetics, and a whole worldview, aligned with Fracturism and therefore predominantly egological, beholden to the poetic ego. Hemmed in by things in ecograffiti, this self “breathe[s] in fear” and searches for “narrow” and “dark” corners to hide (48). But these things are not “in” space, as the contents of a container; they are space, for they make it. Thus, no rooms, no secret abodes, no-thing can mitigate the vulnerability of the self, which flounders and goes under, sinks into objects, mores, situations, and other components of the all-pervasive, sticky or liquified outside. As opposed to Novac’s later responses to a larger object world that flows, spills, and percolates, the impulse here is essentially defensive—pull back, set a buffer zone—although, as mentioned, it is doomed to fail, to try and fail again and again. In ecograffiti, the anthropocentered subject-object dynamic remains cagey and tensioned, if not utterly adversarial. The abhorrent, “unnatural,” and ailing city (“Bucharest opens up as a giant syphilitic flower” [16]) drowns and chokes. Its materiality is overwhelming; everyday things are poised to crowd the subject out, as it were. Only, once more, there is no “out,” no outside to the city’s devouring insides except for paltrily commercial echoes of faraway world metropolises (“On my pack of cigarettes it says / london paris new york” [8]).

Now, while dwelling on an author’s “change” from one book or moment in his or her career to the next is risky and sometimes downright abusive, it would not be farfetched, I believe, to read Novac’s stunning 2020 “comeback” as an inspiring attempt to revisit the poetic subject’s relationships with the world of objects and thus with the world tout court. Alwarda’s world is conspicuously greater, so one immediately noticeable adjustment is a drastic rescaling of the geoimaginary. In ecograffiti, the imagination is, in the main, confined to the nation, particularly to the capital city, and to “culture”; one might even say that the keystone of the volume’s architecture is a metaphorics of confinement, of limitation and finitude. Instead, Alwarda redefines Novac’s poetic world, de-limiting it and scaling the Romanian scenery up. The one-city universe becomes a multiverse of world cities—Istanbul, Detroit, Berlin, and Antwerp—on different continents, while the cultural breaks wide open, unwrapping its intricate overlays and imbrications with the environmental, as in Bogdan Tiutiu, Mihók Tamás, and other young Romanian-language ecopoets. The transnational, the place, or constellation of places, as well as the movement between them, upgrades the national, and the Bucharest flâneuse is bumped up to globe-trotting emigrant. Novac herself has, in the meantime, emigrated to Germany, where she is currently living and writing in Romanian by drawing on her immigrant experience, as have other Romanian postmillennials such as Schiop, Radu Pavel Gheo, Ștefan Manasia, and Andrei Zbîrnea, and, I might add in passing, if Romanian critics have no problem treating German-language works as part of Romania’s literary patrimony, then Novac’s recent poetry, still penned in Romanian, may too belong to German literature, or also to German literature, the way German nationals writing in Turkish do, or somebody like Yoko Tawada.

A more encompassing world of worlds expanding and overlapping, clashing and coming together, successively traversed and transcribed by the poet’s nomadic self, this magnificent world poetry does not thrive on the ampler scale just spatially; the wider scope of travels, discoveries, and affiliations is but one thrust of Alwarda’s ambit. Size matters here also insofar as, beyond the quantitative, it smooths the path of a qualitatively new, ethical approach to existence. What I am talking about is a certain post- or neo-Rimbaldian rescaling of the senses themselves, not just of their environs, a retuning or, to borrow Morton’s musical metaphor, an attunement to objects.²¹ Far from “downplay[ing . . .] human action” or “presence” in the world, this operation recalibrates poetic perception.²² The latter is not only scaled up so as to permit an embrace of remote places “in” the world that were formerly available just as names evoked by imported commodities; it is also scaled down to foster a more intimate and authentic rapport with the world qua world. Above, I have called such a world “worlded.” What I mean by that is a worldly or planetary ensemble of parts aware of, connected to, and willy-nilly depending on each other.²³ With another vocabulary, the worlded world makes for an ecosystem, and with still another, for an assemblage, network, or entanglement wherein the human subject has become an object alongside others and is, as Morton routinely puts it, “always-already” attuned to them, different but in synch with their being-there, somehow a priorily “related” to them, and therefore sharing their fate.

This object- or object-like-becoming of the subject is not typically humanist dehumanization, the depersonalizing “reification” deplored by modernist aesthetics, philosophy, and psychology. While ecograffiti’s feeling of alienation has not subsided completely, such objectification does not necessarily “estrange” the human from other humans but strips it of the exceptionalist ontology sealing it off from nonhuman others and allows it to edge near them, to their level and on their ontological wavelength. Marking a departure from the egological, this move, this swerve, rather, carries the human subject into “[t]he ecological space of attunement,” which “is a space of veering” “because in such a space, rigid differences between active and passive, straight and curved, become impossible to maintain.”²⁴ “When a ship is veering,” Morton asks rhetorically, “is that ship pushing against the waves, being pulled by them, deliberately steering, or accidentally?”²⁵ One is tempted to rephrase: Is the ship, or its captain, the subject here, or is it, him, or her subject to the unfathomable whims of waves and currents? The answer is “neither” (or is it “both”?), for the ship, its crew, and the surrounding “elements” are all objects, bearing on each other in a physical and onto-logical tug-of-war that blurs the “straight” lines between cause and effect and subject and object and queers these classifications altogether.

One might actually submit, as I would, that veering, drifting, and detouring, “deviating” from charted courses and beaten paths, cutting across routes, rubrics, standards, and habits make up the queer and trans mechanics of Novac’s aesthetics in Alwarda. Critics have observed that, aside from the distinctive endeavors to problematize normativity, the critique of “bounded individualism” and “human exceptionalism,”²⁶ as well as the corresponding shift in focus on “[c]onnections, assemblages, and becomings”²⁷ are features of queer aesthetics and consequently “form central concerns for many queer and nature writers.”²⁸ Further fleshing out these concerns is “sympoiesis,” a kindred artistic practice based on “the fact that no being is ever alone, calling out for an absent other.”²⁹ The “sym-” (or “with”-) mode of writing is in turn fueled by a sym-pathetic mode of feeling “with”—about and possibly “for”—others in the world. “[A] feeling of unconditional solidarity with things,”³ᴼ beauty is in Alwarda the corollary of sympoetic intimations accruing from an “ecological attunement” to the “symbiotic real” of ambient objects.³¹ To an extent, ecograffiti paves the way to this supremely insightful convergence of the aesthetic, ethical, and ecological, and it is noteworthy too that they merge and reinforce one another via explicit references to bisexuality in the 2003 book’s first text, as they do by captioning bigender identity in Alwarda prose poems like this one:

Education through sight, voice, touch. A blue light is striking between the shoulder blades. You are flawed, your moves tentative. You are fully regressing, one can work with you but not for a long time. The voice underneath which circuit breakers trip, you are trickling along, the pulse is slowing down. You are sleep deprived, what is inside is leaking out, now you are a little boy scout, a light, blue jacket on your shoulders, stumbling on uneven field in the barley just sprung out of the ground, toward freudenburg, willing to cooperate. You are a girl at the beach at oostende, between dunes, drawing lines in the sand. You are headed to town, your heart is bursting with confidence, the air is flowing. You are gliding through warm darkness, you are recovering in a few hours, you never recover (36).

“Regression,” or “withdrawal,” as Morton, Graham Harman, and other flat ontologists would say in echoing Martin Heidegger³², is just one way of capturing the object condition. The other, more perceptive still, and to which Morton has switched of late, is “open.”³³ The change in critical vocabulary is telling. Objects may be and frequently are rough around the edges, fragile, unserviceable, and difficult to access, “stepping back” when approached physically or cognitively. They risk “attract[ing] prejudices [the way] queer [does]” because they often look “weird” and are “tentatively” there, unstable and elusive, hard to pin down, and eminently amphibological, their essence and meaning running like paint.³⁴ Aquatic or vegetal in a metamorphic topography where plants “flood” Berlin (39) and pretty much everything else (57) while other cities “bleed” (55) or, like the highways (31), become “liquid” (38), this fluidity is an enduring signature of Novac’s imaginary. Dating back to ecograffiti and thus unsurprisingly couched in the language of gender mobility, this liquid ontology sponsors inside and outside bodies not so much a retreat as its opposite.³⁵ The wiring of the self short-circuits only to loosen up and let him or her gush out into a world whose “brutal fluids [. . .] unite people” and things, “welding [. . .] bodies together like an English rave” (55). He or she—he and she, rather, Alward (male Germanic name) cum Al Warda (female Arabic name)—opens up simultaneously inside and onto his or her outside like the rose (ward in Arabic) on Alwarda’s cover, in a show of fragility and strength simultaneously (43, 52). Eager to be out there, the boy(scout) and the girl both tune in to an environment where plants and air in exchange emulate his and her blossoming forth, and the senses map gender complexity onto multiversal ontologies, “teaching” that whatever is, no matter what and how, lies at once this and that side of various lines in the world’s sand.

Whether this is “nature’s queer performativity” in actu or less so, and whether nature restages the sex and gender dynamic of the human or not, attunement bespeaks a sympoetic decision to work through fault lines, “fractures,” benchmarks, and norms rather than ignore them.³⁶ Poem 47 does record a “lack of limits” (64), yet they have not vanished. Blurry or twisted as they may be, broken or softened up and thus enabling objects to swim around and dissolve (64), they have not gone away but keep shifting—“You lie in a structure, and this unfolds within limits,” we learn from “4 anver” (10), whereas poem 54 reports that “the structure is changing, now is slowly moving, you can touch it” (73). Limits, frontiers, and designations, old and new, constitute a reality and a challenge, if not to the bunch of friends driving through “former customs” (“4 anver” [10]) or border hopping around Alsace, their selves present “simultaneously in the air and in the bodies sitting in the car” (15), then certainly to the “Cambodian children thrown [ . . .] in a van, shipped across borders, used for whatever purpose” (“7 colmar” [15]). For, with another musical term, attunement does not bring about “unison” within or without the self, not by a long shot; it does not give rise to a harmonious ecumene. The world it forges is boundless yet not borderless, one of bigger hurdles for the subject to clear and as many dares to leave behind not just a determinate residence, identity, and idiom, but human subjecthood and expression entirely:

But you hate yourself, and so nobody can take your strength away. You come up with a double-edged language to feature it. Grow out of this language, keep at it. Shdjddjddk. Dive down with it, build it up. Turn it into its opposite. Nothing stays the same. Language is not human anymore, it’s the language of animals, of minerals that bump into one another, of objects broken up by wind. The house is not one anymore, it changed into all the houses in which you had ever lived, and then it blew up.

You have overcome the panicked thought—the first one, the hardest to shatter—that you will be swapped for anybody else, that you have already been swapped, unawares. It comes from afar, now it’s here, it’s with you. It’s good you know that now—no, it’s not.

Body fluids are gone, everything is smooth. The world’s fluids lie behind a mercury curtain. You can’t get to them anymore.

Life is getting better, calms down. You are tainted, at last. You have pressed into service your own soul, and it has been wrecked.

Brussels, detroit. The cars and the oil. The industry and its ruins. The city is getting less and less federal aid, it would have to self-consume, and it is doing so but less and less, fewer and fewer resources ([poem 48] 65-66).

Let the original guide us once more. “Swapped” and “tainted,” which modify the poetic “you,” are ungendered, as one would expect English past participles to be. Their Romanian equivalents in poem 48, however, are masculine: schimbat (which comes from the same Latin root as “[ex]changed”) and impur (“impure”), respectively. It also bears noting that both the Romanian and the English words for “change” can be traced, past their Latin and French etymons, to the proto-Indo-European term for “to bend” and “curve.” I would not make too much of this, but I would point again to a movement intrinsic to Novac’s language and imagination and flaunting a “straying away” from putative, middle-of-the-road trajectories, identities, and ontologies. Akin if not identical to Mortonian veering, this deviation-with-transformation is enacted by the poem’s vocabulary and charts, despite gnomic obscurity and fragmentariness, an “impurifying” drift across a world that is as internal as it is external.

More than a “congruen[ce] with an object [ . . .], attunement” sets up the poetic mind and the “inner realm” generally as an object-becoming scene, a space taken over by the non-linguistic language of objects in which the referent and its sign are one and the same.³⁷ “Objectified” and “impurified,” its original contours, markers, and drives shaken up, the “body without liquids” looks on an outdoors whose waters, too, are “impure,” and where cities, similarly covered by “mercury waves on top of mercury waves” (45), are left to their own self-ruining devices, themselves ironically insufficient. Poem 48 thus closes with a clipped enumeration of objects in our shared world, another sign that the roaming subject is divesting herself/himself of Fracturist egocentrism.

What is more, Alwarda casts aside some of Novac’s anthropocentrism as well. The poet is sloughing off her human skin, so to speak, or at least one of her skins, and with it the prehension apparatus and related anthropocentric worldviews that have previously obstructed a less human-centered purchase on the nonhuman, in particular on the Anthropocene story etched into neighborhoods, manufacturing plants, oceans, and other objects scarred by industrialization and its global impact. This purchase, this take, presupposes a giving, as it does a gift, a knack for it, as well as training. The offering is ethical, but, as noted, its ramifications or facets are aesthetic and ontological. It requires, we saw, an affective “education through sight, voice, touch” (36) and consists in a cognate approach to and even a touch of objects’ own skins or “appearances”³⁸ —[t]his is how one gets an education, glued to alien bodies, to objects licking the skin,” writes Novac in poem 31 (44). Yet again, this artistic haptics, this sympoetic “feeling up” of things and of the world (“You will close your eyes and touch the world” [70]), is predicated on the subject’s own shedding of those sensory, cognitive, and cultural layers, barriers, categorizations, and dissociations that get in the way of a closer, in situ association with flora, fauna, things humanmade or “natural,” discards, and whatever else is. To draw closer to others in the world, “meet them halfway,”³⁹ and experience this world as an ecosystem—one surely in deep trouble—the self must fine-tune himself or herself to those others’ presence, to how they present themselves, in other words, to how they appear and to what may lie behind appearances. After all, how and what things are, ontologists like Morton assure us, are two sides of the same coin.⁴ᴼ

Alwarda’s project, it seems to me, inheres in this very attuning to nonhuman things. Rescaled ontologically, Novac’s aesthetics—now a full-fledged onto-aesthetics that bears ethical “withness” to things more than ever before—at once provides and calls for this poetic rapprochement. One more time, this retrofitting of style and vision is not an overhaul of earlier work but a redistribution of emphases and priorities, as poem 10 of Alwarda goes to show:

The city is glowing, spreading light, the forest is wading out into

the sea. We have decided what we have in common:

self-hatred

animals

the horribly decolorated blond hair

looping refuge lanes along highways

the highways themselves actually, washed with peroxide, covered in skin

months of disappearance

machinery, useful because it takes you far away

and gets dumped there, all rusted up.

A couple of years into adulthood it dawned on us that we would

always have a modern sensibility,

what with objects that hit and unify,

what with such a permeable skin (19).

These lines instantiate the volume’s proclivity for dramatizing the self’s struggle to acknowledge and act on the growing adjacency to and commonality with others. These are humans, possibly traveling together across Western Europe and the United States, but they are nonhumans also. Having things in common with other human persons as well as with Morton’s “nonhuman people,” however, has nothing to do with sameness and everything with a sharing of limits and passages across them into domains of being that preserve their distinctiveness during and after crossings and contacts. Terribly polluted, world cities are now their own light source and wake up to “chemical morning[s]” (20) while the woods are encroaching on the rising seas, “touching” on them to give birth to climate-change-era geoobjects such as “sea-forest,” “sea-black-plain,” and “plain-forest” (73). Regardless of location, humans continue to be their own worst enemies too. In the stanzas above and elsewhere in Alwarda, references to self-hatred and self-destruction abound (“Work against yourself. Do all you can against yourself,” urges poem 41 [58]), and, to reiterate, modernist self-alienation does not account for them either. More importantly, whatever the self loses and cannot reconnect with itself anymore opens out to others in the world only to discover their mutual, de-limiting limitations. Thus, humans are like one another because they are nonhuman animals; because they have bad hair; because human hair is bad the way thoroughfares are, and vice versa, because potholed roads look like human beings with damaged skin and curls ruined by peroxide; because “we” all use things to carry us far, and yet we scrap them, abandoning them to oblivion and rust; because “modern sensibility,” the cultural-affective dominant of the Anthropocene, is a thing-effect, a byproduct of objects’ culturally unifying impetus and an index of their ability both to set and “permeate” boundaries, to roll out gossamer “membranes” between different forms of matter but also to trickle through partitions and dividers; and because this sensibility, which is a sensibility to things, a capacity of being moved by them, of reacting ethically to their presence, represents the historical flipside of human insensitivity, of indifference and cynical treatment of nonhuman objects as Heideggerian “standing reserve,” commodities, and disposable utensils. Novac’s recent poetry is a splendid effort to hone the modern structure of feeling into a genuine twenty-first-century perception, one both in touch with objects and responsive to their anguish.

(For a complete bibliography, click here.)

___________________

Footnotes:

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement no. 101001710). My essay has also benefited from help generously extended by Mihai Iovănel, contemporary Romanian literature’s most distinguished critic. I am also grateful to Ruxandra Novac for letting me quote, translate, and otherwise use her Romanian poems in this article.

Dumitru Crudu and Marius Ianuş, “Eseu: Manifestul fracturist” (Fracturist Manifesto), Agonia—Ateliere Artistice, September 9, 2006. https://www.poezie.ro/index.php/essay/202813/Manifestul_Fracturist (accessed on July 3, 2023). All translations of Romanian texts incorporated into this essay are mine.

Ianuş, “Eseu: Manifestul fracturist.”

Crudu, “Prima anexă” (Annex #1), in Crudu and Ianuş, “Eseu: Manifestul fracturist.”

Mihnea Bâlici is one of the commentators who have drawn attention not only to critics’ difficulties to pin down the meanings of Fracturism but also to the fuzziness of the concept itself and of the more programmatic claims made in conjunction with it. See his essay “Fracturismul în câmpul literar românesc” (Fracturism in Romanian Literature), in Transilvania 5 (2021): 2.

Crudu, “Prima anexă.”

Crudu, “Prima anexă.”

As Quentin Meillassoux writes, “[c]orrelationism consists in disqualifying the claim that it is possible to consider the realms of subjectivity and objectivity independently of one another.” With a reference to French phenomenologists Philippe Huneman and Estelle Kulich, the philosopher further explains that correlationist philosophies posit that “‘the world is only insofar as it appears to me as world, and the self is only self insofar as it is face to face with the world, that for whom the world disclose itself’” (Quentin Meillassoux, After Finitude: An Essay on the Necessity of Contingency, trans. Ray Brassier, with a preface by Alain Badiou [London, UK: Bloomsbury, 2016]), 5.

On democratic object worlds, see Levi R. Bryant, The Democracy of Objects (Ann Arbor, MI: Open Humanities Press, 2011), 19, passim.

Christian Moraru, Flat Aesthetics: Twenty-First-Century American Fiction and the Making of the Contemporary (New York: Bloomsbury, 2023), 2.

Timothy Morton, Humankind: Solidarity with Nonhuman People (London, UK: Verso, 2019), 13, passim. For “flat ontology,” see, among others, Bryant, The Democracy of Objects, 19, passim; Ian Bogost, Alien Phenomenology, or What It’s Like to Be a Thing (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2012), especially 11-19; Moraru, Flat Aesthetics, 2-9, passim.

Timothy Morton, Being Ecological (London, UK: Penguin, 2018), 139.

In this essay, I will be quoting from the third, revised edition of Ruxandra Novac’s ecograffiti (Bucharest: Tracus Arte, 2018). All page numbers indicated in the text refer to this edition. In his Istoria literaturii române contemporane: 1990-2020 ([History of Contemporary Romanian Literature: 1990-2020] Iaşi, Romania: Polirom, 2021), 565, Mihai Iovănel calls the original 2003 volume “one of the most influential poetry books of [Romania’s] generation 2000.”

I have theorized the difference between the “egological” and the “ecological” in Cosmodernism: American Narrative, Late Globalization, and the New Cultural Imaginary (Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press, 2011), especially 45-72.

Mihai Iovănel, front-cover blurb in Ruxandra Novac, Alwarda (Bucharest: Pandora, 2020).

“The novelty of this volume is radical,” writes Cosmin Ciotloş on Alwarda’s back cover.

Throughout my essay, I usually give Novac’s poetry directly in my English translation, with occasional references to the Romanian original.

See Teodora Dumitru, “Gaming the World-System: Creativity, Politics, and Beat Influence in the Poetry of the 1980s Generation,” in Romanian Literature as World Literature, ed. by Mircea Martin, Christian Moraru, and Andrei Terian (New York, NY: Bloomsbury, 2017), 271-88.

Iovănel, Istoria literaturii române contemporane, 566.

Iovănel quotes the text to which the line belongs and comments on the poem in Istoria literaturii române contemporane, 544.

Morton, Being Ecological, 139-49, passim.

Marco Caracciolo, “Slow Narrative and the Perception of Material Forms,” in How Literature Comes to Matter: Post-Anthropocentric Approaches to Fiction, ed. Sten Pultz Moslund, Marlene Karlsson Marcussen, and Martin Karlsson Pedersen, 64 (Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press, 2022).

Christian Moraru, Reading for the Planet: Toward a Geomethodology (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2015), 14, passim.

Morton, Being Ecological, 139.

Morton, Being Ecological, 139.

Sarah Dowling, “Queer Poetry and Bioethics,” in The Cambridge Companion To Twenty-First-Century American Poetry, ed. Timothy Yu, 124 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Erickson, “Introduction: A Genealogy of Queer Ecologies,” in Queer Ecologies: Sex, Nature, Politics, Desire, ed. Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Erickson, 39 (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2010).

Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Erickson, “Introduction,” 39.

Dowling, “Queer Poetry and Bioethics,” 124.

Morton, Humankind, 66.

Morton, Humankind, 66.

See Graham Harman, for instance his Object-Oriented Ontology: A New Theory of Everything (London, UK: Penguin, 2018), 38.

Morton, Humankind, 37.

“Like queer,” Timothy Morton writes, “the term object attracts prejudices.” See his article “An Object-Oriented Defense of Poetry,” New Literary History 43, no. 2 (Spring 2012): 208.

I take issue with Harman’s “withdrawal” throughout Flat Aesthetics. For the critique of this term, also see Steven Shaviro, The Universe of Things: On Speculative Realism (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 30-43.

The phrase in quotation marks reproduces the title of Karen Barad’s article “Nature’s Queer Performativity,” published in Kvinder, Køn & Forskning 1-2 (2012): 25-53.

Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 171.

Morton, Being Ecological, 139.

This is a quick nod to Karen Barad’s landmark Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007).

Morton, Being Ecological, 171, passim.

Christian Moraru is Class of 1949 Distinguished Professor in the Humanities and Professor of English at University of North Carolina, Greensboro. His recent monographs include Cosmodernism: American Narrative, Late Globalization, and the New Cultural Imaginary (University of Michigan Press, 2011), Reading for the Planet: Toward a Geomethodology (University of Michigan Press, 2015), and Flat Aesthetics: Twenty-First-Century American Fiction and the Making of the Contemporary (Bloomsbury, 2023). He is the editor of Postcommunism, Postmodernism, and the Global Imagination (Columbia University Press, 2009), as well as coeditor of The Planetary Turn: Relationality and Geoaesthetics in the Twenty- First Century (Northwestern University Press, 2015), Theory in the “Post” Era: A Vocabulary for the Twenty-First-Century Conceptual Commons (Bloomsbury, 2022), and The Bloomsbury Handbook of World Theory (2022).