Fatherlands

The three of us are ten years apart, neatly generational, one after the other. Our fathers died on the same week, neatly spaced, one after another. They were all some kind of old. We tell ourselves they’ll come back as something or other, these fathers. Dust in the wind, these fathers. Two of us are cremators. One of us disappears. But you. You come from a long line of revolutionaries. You wouldn’t tolerate such things. You embalm your father, then keep him in your living room to answer any last questions we might have, which could stretch to eternity.

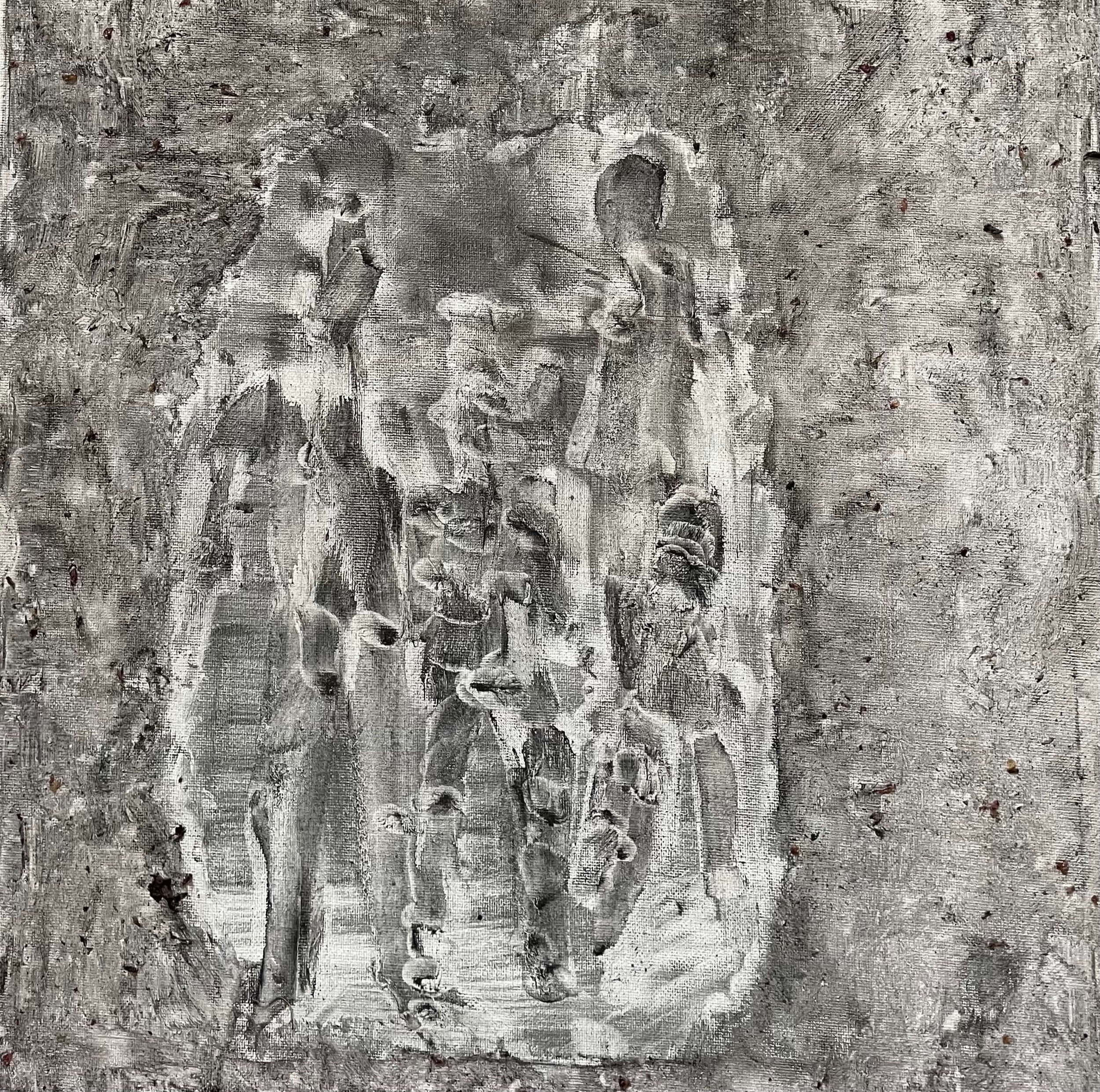

I want to tell you, I also want to keep my father forever, but I’d be missing the point. You don’t burn or bury your people. You prop them up in caverns in cliffs where they guard the path — upwards, probably — to another hinterland. The promise of anything else. It doesn’t have to be more.

***

“This is the last generation with physical hinterlands,” your father used to say. Part threat. Part mourning. Your mother named their unruly dogs Lady Gaga and Sandinista.

“Both revolutionaries,” he would remind us, when he was alive. Now they roam free, as they were always meant to, bellies round from full bowls every morning.

***

My least favorite cousin comes to ask what’s been left behind so he can take it for himself. I don’t know what to say, so I tell him, “Come back again tomorrow.”

When I tell you he’s been by, you say, “It’s not your job to be nice to anyone.”

You are endlessly cheerful, energetic. “I have to go,” you tell me. “Typhoons.”

***

The weather finally comes in. I lose power, then it returns. Dollars and unhappiness flow in as local economies pick back up, stall, then flood. The McDonald’s Drive Thru window is open, but only for greetings. “We can’t make food,” they tell me cheerfully. “We have no power.”

***

“I’ve earned the right to be whatever I want,” my mother says.

“I just,” I say, “want you to be happy.”

“I’ve earned the right to be unhappy,” she says.

I can’t think what to say. So I ask, instead, about a schedule. I ask, instead, “how long?”

“I don’t know,” she says.

We don’t speak to each other for six years.

***

My cousin comes back to say, “I’m taking everything.” I can’t think of a reason why not, why one of us would be more entitled to anything than the other. I can’t think, really, of anything. He starts a fire to burn what he can’t take. He kicks at the edges of the fire like a little kid. Embers and charcoal and bits of things that belonged, once, to someone, maybe to my father, maybe to me, fly into the air, dust in the wind. A tiny hot coal arcs and bounces and lands in my eye. Some words you can feel, like sear, like loss. When you come by, my cousin has left, and everything is gone. You decide then and there to take me in. When I enter your home, your father says, “What is the point of being alive if you’re just going to let things happen to you?”

***

You tell me a story about a man. He has the name of a girl.

When he was born, he was born in a forest. After he was born, the forest became a national park, a symbol for a newly minted nation, independent, free. His family said, “It doesn’t matter, we’re still here. It’s just the name of a thing, not the thingness of a thing. Nothing has to change.”

The new nation said old things.

The new nation said, “The name of the thing says the thingness of the thing is that you’re not allowed here anymore. This forest provides 40% of the water for a major lake that hydrates and aerates and nourishes two countries. The thingness of the thing doesn’t include nourishing you.”

His family said, “It has and it does,” but the new Powers that Be sang the same song as the old Powers that Be, and all the Powers in Between and After, Forevermore.

After a while, what’s the point in hanging on?

After a while, what is there to fight for? And so, they left.

***

I have the name of a boy. When I was born, I was robust, bursting with life, enormous and strong. They gave me a gladiator name. Infinite justice, for a warrior boy. In the nursery, old aunties coming by to dote on their grandlings saw me pushing against the bassinet, a few days old. The old aunties tutut-ed and said, “Oh this one has been abandoned, it’s three months old.”

***

“We are disappearing,” you say, then shout, on behalf of more and more.

My indulgence is to shrink and shrink, become small.

“Are you still here?” you ask.

“I’m not running away,” I say.

“When you need me,” I say, “ I can still hear you.”

Sometimes I am delayed, and sometimes I hang up or disconnect or don’t pick up. You don’t pick up, too. Neither of us believe in shame. Neither of us believe in regret, whether we have regret or not. We call over and over again. One of us doesn’t pick up. We call over and over again, until it works or until it fails, forever. Maybe that, too, is a kind of love, the kind that leaves connection to destiny. The kind that is accepting of, or is left entirely to, chance.

***

“Are you still here?” you ask.

“I am,” I say.

“What is going on in America?” you ask.

“Will the kids be okay?” you ask.

“Forests are on fire all the time here, too,” I say. “Everything is the same everywhere.”

I am endlessly cheerful, energetic. You are not sure if I’ve lost my mind.

“Come visit!” I say.

“Okay,” you say.

You ask for the things you need. You shout gargantuan tasks in impossible timelines down what sounds like a tunnel the smaller I get, the fainter. “It’s okay if you can’t,” you say.

“Of course,” I say, “I can.”

***

“This,” someone says, “is about grief, is about loss.”

“This,” someone says, “is about displacement. The refugee mentality.”

“This,” I say to no one, “is about common sense.”

***

Instead of asking people where they are from, how come we don’t ask them who they love? In either case it’s none of our business, and it’s not worth having the conversation only once. We try and we try again. We try to have it over and over, every millisecond of every day towards the hope we can be whatever we want. Yes, unhappy too.

***

Lady Gaga and Sandinista break into your house and tear up your Bible. I never even knew you had one. You find them lying on torn pages, waiting for you to come home. Your father is silent, disapproving.

“They are reformed,” you say.

“They came back looking for their Christian names,” you say.

“They tore out specific books,” you say.

“Henceforth,” you say, “they want only to be called Luke and Lamentations.”

They never leave your house again.

Ho-Ming So Denduangrudee lives in Truckee, CA.