Include Everything

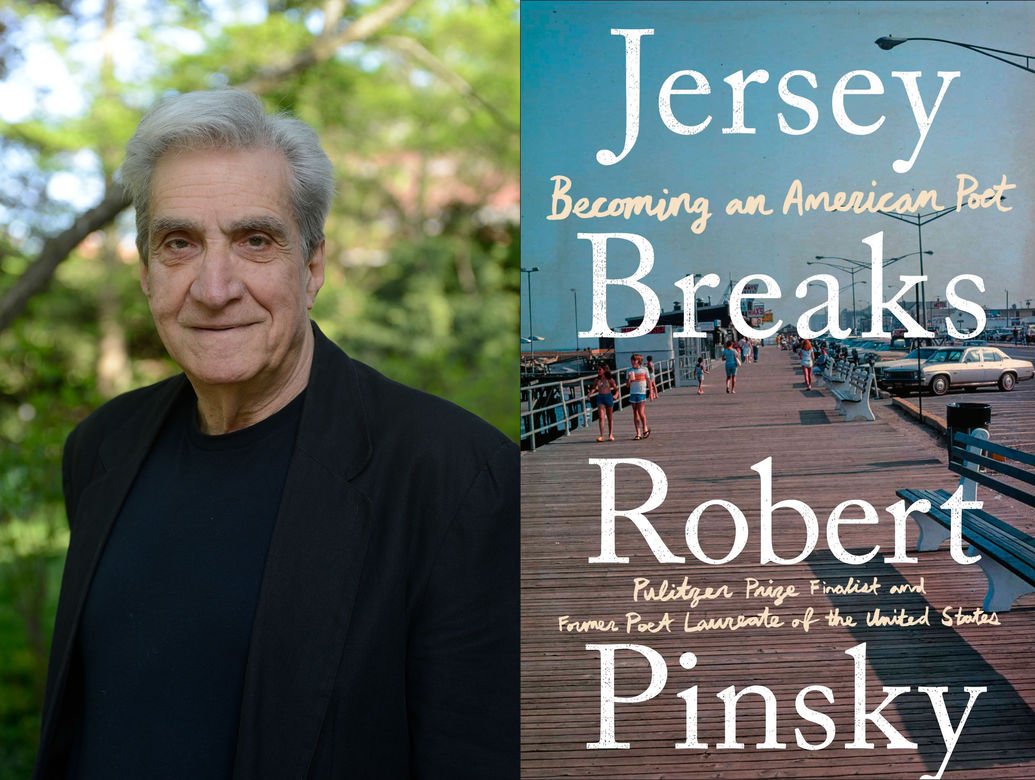

Jersey Breaks: Becoming and American Poet, by Robert Pinsky

W.W. Norton

256 pp.; $17.95

In one of my favorite Robert Pinsky poems, “Shirt,” from his 1990 book “The Want Bone,” the small act of putting on a dress shirt fills and swells and finally overflows with meaning, matter, and music. The poem takes us from the fine material of the present moment, “nearly invisible stitches along the collar,” across the globe to Malaysia where sweatshop workers gossip as they fit overseam to cuff, back to the poet’s own wrist, into history, to “the Triangle Factory in nineteen-eleven,” the women leaping from the fire to their deaths, to mill-owners in the United Kingdom inventing kilts to better control their Scottish workers, to the sweat of slaves in cotton fields in the American South, back to the buttons of the shirt, their “simulated bone.”

An epic poem, according to Ezra Pound, “is a poem containing history.” For more than half a century, Robert Pinsky has written poems that don’t just contain history but overflow with it. There are politicians in his poems, and jokes, and ghosts, and televisions, and love. Buckets of mops. Fats Waller playing a piano the size of a jewel box. Pinsky is a poet of litany, a poet of the dazzling detritus of the moment, the “gasoline rainbow in the gutter,” “macaroni mist fogging the glass,” “pale honey of a kitchen light,” “dried mouthbones of a shark.” In more than a dozen books he has excavated the human heart and sung its history. For such a poet, a poet whose books include, “History of My Heart,” might the idea of a memoir seem a bit… superfluous? Well, Robert Pinsky is our great poet of the superfluous — from the Latin: superfluere, to overflow. It’s no wonder that gutters, open vessels for the overflow, reappear in his poems — and that there are often rainbows in them.

The pigeons from the wrinkled awning flutter

To reconnoiter, mutter, stare and shift

Pecking by ones or twos the rainbowed gutter.

from “First Early Mornings Together”

As a freshman at Rutgers, Pinsky taped Yeats’ “Sailing to Byzantium” above his toaster. “Without noticing,” he writes, “I got it by heart.” The poem stunned him “with its final assurance to include everything: what is past, and passing, and to come.” His memoir, Jersey Breaks: Becoming an American Poet, is another of his valiant attempts to “include everything…” and then some.

The story of this becoming unfolds in a very free interpretation of the chronologic; rather, it unfolds like a Coleman Hawkins solo. Pinsky’s first love was the saxophone, and when he writes of his playing, “I loved the sound of returning to a theme with more emotion each time with each chorus, building, turning or expanding,” he could be describing the way this memoir moves. It starts in Long Branch and, though it takes us to Palo Alto and Cambridge and Berkeley and Washington, DC, and North Korea (North Korea!) it proves that while you might take the boy out of Long Branch you don’t take Long Branch out of the boy. This Jersey seashore resort town, with its “blends, resistances, suspicions, borrowings, intermarriages, rivalries, and molten alloys of American cuisine,” is Pinsky’s Byzantium, the source of his spiritual philosophy. It is the sort of place he describes elsewhere in the book in which “everything can feel simultaneous,” which is also the place in which lyric poems exist, a sort of historical present, a history of the present.

Growing up in Long Branch with his innate attraction to its contradictions and “mishmosh” helped Pinsky to forge that most essential of poetic faculties: negative capability, the state of being — according to Keats — that allows one to rest “in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” In the chapter “Naming Names,” he puzzles through the vicious American racial setup (and it is a setup!), his awareness as a child that his “Pinsky” was not the asset his neighbor’s “Weaver” was, or that Protestant-sounding names of Black people had a nightmare history in slavery. “I felt the need to understand,” he writes, but also “to include in the effort all of my own uncertainty and confusion. My ignorance itself began to interest me. Confusion could be more interesting than purity.” Negative capability, a sort of anti-mastery. After all, “the real masters,” Pinsky concludes at the end of a meditation on the artist’s relationship to posterity, “have above all a total, consuming devotion not to fame or profit or pleasure… but to difficulty.”

Like his poems, the book balances the pricks and kicks, the belly laughs and the tearing of hair — and it’s a wobbly balance. A dance. There’s his mother’s flirtatious Hitler jokes, her head injury and debilitating depression; there’s the story of his grandmother, Rose, who dies after childbirth, and how his grandfather the bootlegger, Dave Pinsky, goes after the doctor with a pistol but is stopped, and how Rose’s family then supplies Dave with a new wife, Rose’s cousin Molly, who later dies in the state mental hospital and is buried with no formal grave or marker in the Long Branch Cemetery along with Rose, her “famous beauty” preserved in an oval frame on the headstone in the shape of a tree with its branches lopped-off.

And there is the story of the poet Henry Dumas, whose poetry has become — posthumously — a landmark, and who was Pinsky’s friend in Freshman Composition Class at Rutgers in 1959. Less than ten years later, Henry (who was Black) was killed by a police officer who claimed both self-defense and mistaken identity. Considering the term “white privilege,” now in his eighties and thinking back on Henry’s death, his talent, his place in their composition class, Pinsky concludes, “Privilege’ may be too mild an understatement.” The professor of that English composition class, Paul Fussell — author and war hero — serves as one of the book's most poignant portraits. It is under Fussel’s gaze — a gaze of “not-quite-scornful irony,” but also respect — that Pinsky begins to believe in his own poetic calling. In what is perhaps the best description of a great teacher or mentor that I have read, Pinsky writes that Fussel “recognized [the true poet] in me, and by letting me know that he did, he helped me recognize it in myself.” Pinsky would go on to have many other great teachers, great peers who taught him things — Yvor Winters, Thom Gunn, Csezlaw Milosz, to name a few — but we get the sense that after that freshman comp class with Fussell, Pinsky knew for certain “what poetry had to do with the rest of life.” Everything.

Before Fussell, he did not excel in anything as a student. He got C’s and D’s and only got excited or motivated about playing the saxophone and learning Spanish (a class in which he got a B-). New ways to be heard. Even before he found it in poetry, we get the picture of a young man hungry to stretch the bounds of communication. He seemed to be asking, “how else can I say all there is to say?” As he writes in “History of My Heart,”

Listen to me the heart says in reprise until sometimes

In the course of giving itself it flows out of itself

All the way across the air…

There is a wonderful Zelig-like quality to the way Pinsky has moved through life, becoming, always, a poet, never arriving, remaining open to all of it, whether he’s writing an early computer game, Mindwheel, in 1984, or translating Dante’s Inferno, or serving as Poet Laureate of the United States (PLOTUS), or doing a cameo on The Simpsons, or being detained by the authorities in North Korea — it all serves in his quest to include everything. He eats it up with “omnivorous reverence” and can barely believe his luck.

While serving as PLOTUS, Pinsky created the “Favorite Poem Project,” in which he and a number of volunteers collected hundreds of videos of Americans from all walks of life reading their favorite poems. The videos were broadcast on PBS, and it remains, to my knowledge, the most successful fulfillment of the laureate’s task of bringing poetry to Americans, a democratization of what can be mistaken for an ivory tower art. And it didn’t bring poetry to people as much as it brought to light the treasure of poetry already there, deep in our culture. In a passage near the end of the book, as he reflects on the thrill of hearing all the different regional accents, sometimes different languages (not all the poems chosen were in English; this is America, after all), Pinsky writes, “the vowels and consonants, and the different sentence shapes of meaning: all are unique, and unique each time. Each language, each person, each voice each time it speaks has a different adaptive, history-saturated character.” Saturated, I would add, to the point of overflowing — the way a freshly dyed shirt can color everything it touches.

John Okrent is a poet and a family doctor. His poetry has appeared in Ploughshares, Plume, Poetry Northwest, Field, and The Seattle Times, among other journals. He was chosen by Carl Phillips as the winner of the 2021 Jeff Marks Memorial Prize. His first book, "This Costly Season," was published in May of 2022. Okrent works at a community health center in Tacoma, WA, where he lives with his wife and two young children in a fisherman’s cabin on Puget Sound.