Three Notes for John Berger

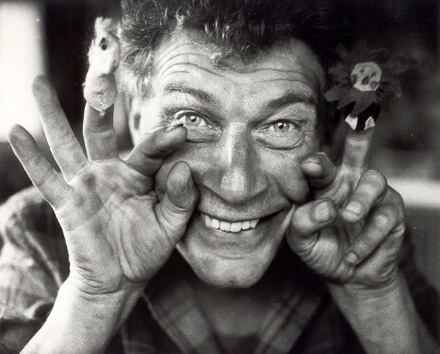

John Berger, 1980 (Jean Mohr)

1. Berger and the Adult

When John Berger died in 2017, the obituaries seemed at a loss to describe what exactly he had been to the arts. No historian of art, since he did not rely on his own research; no art critic, since he rarely wrote about contemporaries; no theorist, since he did not forge new concepts or frameworks — he was not of the art world, and yet through him something was allowed to breathe and speak into the arts that otherwise would not have found a place. The contradiction inherent in his position was that despite being unique, it also consistently left an impression of perennial commonality. People must have been thinking and writing like this, forever — though they have not.

With Berger’s death, I think, arts and letters lost one of their last true adults. I use his own definition of the adult, which he applied to James Joyce: “a being who, because he has accepted life, is intimate with it.” That intimacy spoke through his writings, though everything he ever wrote felt belabored. He never had the effortless flow of a genius or a professional hack. What was effortless for him was the search for closeness. Never, not once, did he hide behind borrowed concepts. Always, without exception, the form of his writing molded around the process of his coming to terms with what he saw. Few writers have stacked up such a vast range of explorations in form as Berger did in his fiction and criticism. These were, however, not experiments per se, but expressions of independence and familiarity.

“But go on looking,” he insisted in his Ways of Seeing, the television series that made his reputation as something resembling a critic. The contrarian directive (“but go on”) depends on a promise made to the public: that through coming to terms with the seen, one is capable of penetrating the work of art. The emphasis for him was on the work, the labor of shaping the world, to which humans have open, if unequal, access. He was an adult in regard to this willingness to participate in work and love, without the need for palliatives. This was a more dangerous enterprise than one might imagine. He extended an invitation to the reader at a time and under conditions that, he knew very well, resisted his call. To appeal, he exaggerated wildly, oversimplified, concocted stories, poeticized, promised. Other critics — watch Susan Sontag interact with him in their 1983 debate on storytelling — regarded him with a mix of fascinated respect and disdain. Until the end he belonged to no movement or community of professionals. Of his own relationship to the art world he said: “Sometimes I read in a newspaper that I am (or was) one of the most influential writers about art in the English language. Yet I know nobody in the art trade in Paris or anywhere else. Nobody. [I would not] get past any art expert’s first secretary.”

His writings on art often begin with an observed mystery: Why does the air in Vermeer’s paintings feel like water? Why do the Fayum mummy portraits seem like they were painted yesterday? Why do we look at animals? Why do suits sit awkwardly on peasant bodies? In And Our Faces, My Heart, Brief as Photos, his masterpiece on the experience of time and space, an unnamed lover asks him, in bed, who is his favorite painter. “I hesitated, searching for the least knowing, most truthful answer. Caravaggio. My own reply surprised me.” Why, he asks, should there be no painter “to whom I feel closer”? From this little mystery ensues an exploration of darkness, interiors, crowds, the poor and the human skin in Caravaggio — crammed into five or six brief pages that are as thick with drama and labor as the painter’s own canvases. With Berger we lean close to the object, not as passive observers, but as grown persons capable of creation.

His approach was so simple that one has to wonder why it has not found any true heirs, not even among his few protégés. Many writers are more erudite, more observant, even more forthright than Berger, who was not above sacrificing his sense-observations to his Marxist sense of history. But who is as reckless as he was, so constantly on the verge of failure? Who would posit that Goya painted flesh as edible, and then push this position to its ultimate conclusion about Goya’s guilt, self-torture and redemption? He did not create theories, concepts, or inventories. Instead, his criticisms were sensations turned into sentences. Their great certainty lay in the fact, the miracle, of their having been produced at all from the raw material of genuine and prolonged first-hand encounters. His writings seemed, intentionally or otherwise, to invite us to read as if we were the indulgent but unsparingly serious parents of the writer.

2. Berger and the Child

I fear that along with one of the last true adults, we may have also lost one of our last eloquent children. In that childhood, maybe, is the secret of his inimitability. Watch Berger, the man, read aloud one of his writings. He scrunches his deeply lined, Hellenic face into expressions of delight at his own ideas. When he makes a clever point, he looks up at the listener, as if to make sure that the surprise and fun are shared. His hands, too small for his body, make unnecessary gestures, clarifying his references to the smallness or vastness of things. His voice rushes through a barely perceptible speech impediment (photogwaphy, owigin) then slows down to a grind to emphasize the sonority of a sentence that has obviously thrilled him, once again, as if at the moment of its inception.

He, the child, is of a certain age: not much older than nine years. If he is surprised by his own ideas, it is because he has entered the period of mental growth in which he knows that there is reason at work in the world, but his faith in this reason is not complete, not second nature. He is not that far from the age in which things do not happen for a cause, but out of internal necessity. Reason, for him, has to be drawn from exploration into that chaos, and it always comes headfirst against the general unreasonableness of lived experience. Particularly, it must be earned despite, perhaps even against, the unreason of cruel fates: that of the poor, the tortured, and the displaced. To understand this child, we must go against the modern tendency that tries to shield children from pain and, therefore, history. Only then we can see in Berger the child’s bewilderment working itself out through direct, personal effort:

“The poverty of our century is unlike that of any other. It is not, as poverty was before, the result of natural scarcity, but of a set of priorities imposed upon the rest of the world by the rich. Consequently, the modern poor are not pitied...but written off as trash. The twentieth-century consumer economy has produced the first culture for which a beggar is a reminder of nothing.”

To compare the treatment of the poor with that of trash is not a rhetorical move. It is an expression of something that one sees, but one might willfully ignore. There is no such ignorance in Berger. His ‘Why’ questions all have this child-like seriousness to them. Who other than him would offer that William Turner’s visual style might hark back to the painter’s watching the world swirl in the mixture of foam and vapor on the mirror in his father’s barbershop? Who but someone in possession of his own early mind could retain that idea? Who else would hold on to the feeling that Michelangelo’s Ignudi, those writhing male figures on the corners of the Sistine frescos, twist their bodies because they “have just given birth to all that is visible and all that is imaginable and all that we see on the ceiling”? From the glint of pearls and the stillness of the dark blue in Vermeer’s Woman Weighing Gold he would leap to the night sky: “Despite its apparent celebration of prosperity, this painting is about the mystery of light and time as we look up at the stars.”

3. … and the Dead

A nine-year-old, newly entered into reason, is also new to something as strict and final: the certainty of his own death. The child at this age shows a funny proclivity for enclosed and secret spaces. In these nooks and corners, under tables or behind the bushes, the child steals himself away from the world to feel the stirrings of a newborn soul. Well into his old age Berger remained a smoker, and he thought of cigarettes as “a parenthesis” within time, separated for reflection. If the parenthesis is shared, then it becomes “like a proscenium arch for a dialogue.”

He once said that all he wrote were stories. He characterized stories as shelters, wayworn travellers huddling around a fire, perhaps, or soldiers who have survived the world gathered in a tavern. “But then,” he added, “inside the story is another kind of shelter, because what the story narrates and tells is sheltered, within the story, from oblivion, from forgetfulness and daily indifference.” The child takes shelter within a story. The adult preserves the shelter, expands and shares it. This is the conservatism of the adult — who “accepts life” — but in Berger it is so mingled with the freshness of experience, of shock at pain and unreason, that true art for him conserves only that which transcends the works of those he called “the torturers.” The ultimate power of his writings springs from an attempt to redeem from dismemberment and oblivion those who have been lost — he writes from a perspective that simultaneously belongs to the living and the dead.

For the last four decades of his life, he turned again and again to the problem of time and death. He knew that capitalism, in its total administration of society, has rendered time unambiguous. All is a loss, a constant and regular process of elimination and entropy. Death has become bereft of the source of its meaning, which is return, reabsorption, reconciliation. It bothered him that the modern view of time had become an intuitive aspect of our thinking and feeling. “The left and right, evolutionists, physicists and most revolutionaries all accept… the nineteenth-century view of a unilinear and uniform ‘flow’ of time.”

His late writings constantly pull against that common notion of time. Often he begins with the child’s experience of time as passing at different rates. He knew that engagement and interest, dreams and imagination, sexuality and love, all defy the uniformity of measurement. They slow or expand time, and they refer to one’s own past experience whose roots run deep, through the dust, into history and prehistory. In Here Is Where We Meet, his beloved dead rise, each in a different city, to reveal to him the surrounding space as only they could. His dead mother is now living in Lisbon, which she had never visited or mentioned. A dead lover has moved to Islington, his first teacher to Geneva. In the Chauvet cave, under the gaze of Cromagnon paintings, a friend dying many kilometers away makes an appearance. Art, whose model for him was love, and which was, like love, inseparable from hope, was a shelter for the vast ambiguity of distance and death. He wanted you to realize that when you stand before a true work of art, if you risk the act of observation, then you stand in that moment which, though not redemption itself, is separated from redemption by a mere breath.

There was an address in his writings. He constantly invited the reader in, spoke to him or her directly. He gave directives: “Watch!” “but don’t stop there!” “let’s try…” In some moments he broke the wall of time and addressed his subject as well. He called Titian and Spinoza “you,” and Rosa Luxembourg by her first name:

“Rosa! I’ve known you since I was a kid. And now I’m twice as old as you when they battered you to death… You often come out of a page I’m reading — and sometimes out of a page I’m trying to write — come out to join me with a toss of your head and a smile.”

The invitation, whether to the reader or the subject, is an act of friendship. The friend is a product of childhood openness to the world. But only the true adult can share a friend with others, to take real pride in that existence which already belongs to the past.

The years to come will inaugurate the search for a type of friendship in art, of which John Berger is, for now, a last great example.

Houman Harouni was born in Iran, 1982. He is a lecturer at Harvard University, and his writings on education, philosophy, the arts, politics, and history of science have been published in The Guardian, Harvard Review of Education, American Reader, and the White Review, among other venues. His first book of poems, Unrevolutionary Times, was published by Arrowsmith Press in 2022.