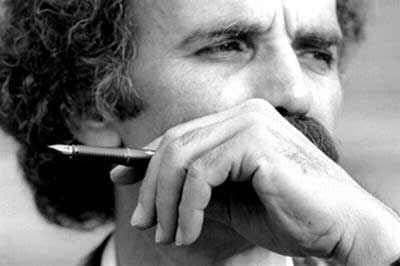

It’s Still Night, Mr. Golshiri

The death of Golshiri meant the loss of a standard of excellence, and a point of reference for Iran’s literature and intellectual movement.

I had recently returned from the war, alive, when (with the help of my professor Dr. Abbas Milani) I was introduced to Golshiri. The first time I met him was at his house. I was twenty-eight years old. Dismissed from teaching at the School of Fine Arts, he was then a stay-at-home father. I read one of my stories to him. It was then, when he started to review and analyze that story, that I realized that my patience was being rewarded. The patience of years and years of persistence in writing, and in hiding all of my exercises and my development from the eyes of others, was being rewarded. My first reader was also my worthiest. While making tea he said, “I do not believe in writing prodigies, although I wrote the Prince Ehtejab when I was only twenty-eight.”

His criticism was not like that of a typical critic. In Thursday's story-reading sessions, or in more private meetings, he let his fictional imagination bleed into the story. In his moments of epiphany, he could even read a story’s “subconscious” — this is the kind of critique that encourages an author or reader to search for underlying layers or sources of previously unearthed potential in a text.

In the story-reading sessions, he said repeatedly that a writer should never take direct aim, but should shoot slightly off or even away from the target. I think that when Golshiri expressed this idea of aiming to miss, Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast had not yet been translated, and the American author’s idea of the “iceberg” with only one-eighth of the story visible to the reader wasn’t part of the conversation. Even if it had been, it didn’t matter — some writers can’t imagine a writer’s deliberately avoiding narrating a story journalistically. By not aiming for the bull’s-eye a writer will find a way to carve circles around it, thereby creating additional targets. By telling his tale slant, a writer invites a limited number of readers today to grow into an unlimited number of readers tomorrow (because tomorrow’s readers are always smarter).

The unique off-target style of Golshiri’s is detectable even in his earliest work, especially in the stories in My Little Prayer Room. In the title story, the spine (or central object) of the story is the red piece of flesh without a nail situated next to the narrator’s left little toe. Golshiri transforms this mini-finger into a metaphor to express alienation, pointing both to the melancholic philosophy of Camus in his novel The Stranger, and to a sci-fi version of it. My Little Prayer Room is the self-portrait of a 35-year-old man who narrates the history of his supernumerary toe. The narrator states, “It is something that separates me from others.”

During his writing life, Golshiri created many brilliant stories with powerful plots. Although the plot of My Little Prayer Room is not one of his best, I believe it embodies Golshiri’s writing manifesto and the center of his attention from his youth until his death:

I only look for and wish for things that I really want. Besides, I think that everything has something seemingly superfluous or something absent that’s more central and revealing than the thing itself, that if it were seen, if everyone would see it, you wouldn't consider it superfluous. When it becomes part of that thing, part of its structure, then it is laid bare, is in the sunlight, like a room that has only four walls, a ceiling and no shelves, yes, that is the loneliest and most pitiful room that you can imagine. If I were a religious man, I would certainly build myself a little prayer room.

In a society as hemmed in by censorship and oppression as present-day Iran, the six-toed man, or Golshiri himself as a writer, as soon as he ceases censoring himself and reveals his singularity, will meet with rejection and possibly worse. The instinctive and unconscious fear of aliens (such as those dramatized in Close Encounters of the Third Kind) is the root of this social rejection.

Consider the reaction of the lover whose name the narrator deliberately conceals in order to guard her uniqueness.

Her name… no, no need to mention it. Just like this piece of flesh next to my little toe on my left foot that I won't allow any stranger to see. The next morning she woke up before I did. She was sitting by the bed, on the floor, looking at my feet. I suppose that I woke up from the touch of her two cold fingers. She asked, ''What's this?” I said, "What?” I pulled together the toes on my left foot in such a way that she would forget she had seen them. But I didn't even try to bend my left foot a bit, or hide my foot in the softness of the mattress. She had seen "it.” So it was over. And she was finished with me.

In the first layer of story, the sixth finger is the incriminating evidence that proves that the narrator is an alien.

Most Iranian fiction remain under the influence of Romanticism and the spirit of Victor Hugo. Golshiri, on the other hand, exposes the multiple hypocrisies and weaknesses of his characters, including the intellectuals. His prose strips away the camouflage of the “literary” to expose more literal realities.

His enigmatic style challenges his readers. His prose aims to reconstruct and defamiliarize conventional syntax, along with various stereotypical Persian tropes. He writes: “Have you ever recorded your dreams in order to determine whether or not you were really in love? Sometimes literature can play the same role as dreams. I started writing Christine and Kid in hopes of better understanding the world and getting a handle on my role in it. That was my most rewarding writing experience. While shaping my story, I was at the same time creating myself and defining my relationship with others.”

In writing about that supernumerary appendage, the writer is striving both to understand and to shape it. Studying that toe gives the writer insight into his character’s personality. This leads to the recognition that we dwell in a world with billions of beings, each of whom possesses her own version of that extra toe.

Note how the narrator of My Little Prayer Room feels proud despite his desolation and sadness. Because nobody else has such a toe, to him it seems unique, like The Little Prince’s rose. I observed that Golshiri himself was as unique as The Little Prince’s rose, but, I added that he, like all roses, also comes with thorns. Some of his admirers didn’t appreciate the analogy, although he never said anything. I’m hoping he recognized the compliment, offered in language as blunt as his own.

His rough frankness and his penetrating gaze, seeing into the essence of people and exposing what they tried concealing behind their masks, made him plenty of enemies. Moreover, he spoke as he wrote. His style of critique was based on methodological criteria, with clear standards and a systematic review process. He was never glib. Unfortunately his critics were too often both sloppy and nasty.

Golshiri once wrote a detailed critique of a novel by one our famous writers and critics. It was clear he’d spent a lot of time analyzing the writer’s work and identifying its flawed technique. Out of revenge, Mr. Famous Writer not only named a Savak agent after Golshiri, he went so far as to note in a response to one Golshiri’s scathing critiques: “I meant Houshang (Golshiri’s first name) the Savak agent, not Houshang Golshiri the writer.”

Golshiri’s bluntness was often impolitic. He once ran into a left-leaning critic in a bookstore. The man had accused contemporary Iranian writers of ignoring social problems in their work. Both men had noticed the Mourners of Bayal on a bookshelf. The critic sniped: “What is this? There is no way a human being transforms into a cow.” Without missing a beat, Golshiri quipped: “How then do we account for you?”

You won’t find that “socially-conscious” critic’s signature on any petition or declaration against the Shah or the Islamic Republic — he never struggled with censorship and or the dictatorship. Meanwhile, Golshiri and others like him, who were accused of dwelling in ivory-towers, signed many petitions. Countless times I saw Golshiri holding a petition or an open letter of protest to send to cities around the country for signatures. The famous statement by 134 Iranian writers “We Are the Writers!” was one of these.

Here I should note that although they didn't dare to kill him during the period of their so-called “chain murders,” they may have killed him more subtly. During the terror of the “chain murders” his wife began taking extra precautions. She even accompanied him when he went out to buy cigarettes. These safety measures made the playful Golshiri mad. In his work and in his person, Golshiri was of a piece.

A central quality of Golshiri’s prose was his skill at noting minute details. While an omniscient point of view remains the dominant narrative mode in Iranian fiction, the use of the first person had been introduced by Sadet Hedayat’s novel Blind Owl, first published in Bombay in 1937. Golshiri was Hedayat’s inheritor. In one of his regular Thursday critique sessions, Golshiri quoted Nima: “If I create a precise description of algae growing under a bridge in a village, the reader should be able to imagine that entire village.”

One of the most beautiful moments in Golshiri’s under-appreciated novel Mirrors with Doors takes place when the narrator leaves his mystic ethereal lover to return to his chipped-tooth mistress. It’s the chipped tooth that makes her real. In Mirrors with Doors, Mina picks up an autumn leaf from the ground and encourages the narrator to observe it carefully. Then she throws away the leaf away and asks: “…Now try to find it. See, this is our problem. I believe I should sit on the ground and peruse one of these leaves under a magnifying glass until I am able to detect every capillary in every one of its thousands of networks. That would be the right way to honor the fall.” Golshiri gazes intently at words until he is able to see their capillaries.

Another of Golshiri’s additions to Persian literature was his pursuit of the subjective point of view pioneered by Hedayat. The subjective point of view rejects the arrogance of an omniscient perspective. At the same time it liberates the narrator from the constraints of realism. Nothing from outside the perspective enters into the story.

There are only a few perfect realistic love stories in Persian modern literature. Most of contemporary romances lapse into sentimentality, as was common in classical literature. The speakers in our poems and our prose either utter admiring sweet nothing or flirt with mystical and unreal lovers. The poet dares take no pleasure riskier than circumventing a lover’s mole with his finger. The writer neither possesses initiative enough to move upward to the mind and thoughts of the human lover, nor courage enough to inch his hands downward.

Golshiri’s Christine and Kid is, however, one of the few successful stories that does both. It’s therefore no surprise that the novel has not been welcomed by Iranian audiences. That same critic Golshiri dressed down in the bookstore described the book as amalgam of Golshiri’s sexual obsessions and fantasies. Instead of entering the fictive world of the novel, the critic wondered whether its creator had ever had sex with somebody named Christine.

Golshiri’s stories revel in multiple meanings. They change with each reader. In his story First Innocent, villagers make a scarecrow to scare crows away from their fields. As time passes, they begin gossiping about the scarecrow, launching rumors about its dark powers, decking it out in nightmarish outfits of their imagining, and in so doing turn the scarecrow into a monster everyone suddenly fears. The story can be read as a parable for a citizen’s relationship with the state.

In Mirrors with Doors Golshiri writes: “Yes, we are sad, or I am, I know, but that is what it is. Maybe the next generation will be able to talk about more cheerful things, about the grass, say, the grass as an entity, grass that is the symbol of nothing but itself.” The voice here echoes the melancholy of the little girl in My Porcelain Doll who builds for her doll a prison of matchsticks.

I miss you very much, Mr. Golshiri. In the prison of our days, we Iranian writers could at least look forward to the freedom of Thursdays. If I could be sure that on the other side of this life there would be Thursday story-reading sessions, I would buy a bus ticket to that Tehran, just to read you a story. You had no choice, Mr. Golshiri. You were doomed to display your sixth toe. That toe is nothing less than literature itself. Mr. Golshiri, there are no Thursdays anymore. They say that in Iran it is always Friday. It was still night when you left. It is now even darker.

Translation by Delaram Mehrdad

Shahriar Mandanipour (Mondanipour), one of the most accomplished writers of contemporary Iranian literature, has held fellowships at Brown University, Harvard University, Boston College, and at the Wissenschaftskolleg in Berlin. He has been a visiting professorship at Brown University, where he taught courses in Persian literature and cinema. He also has taught creative writing at Tufts University. Mandanipour’s creative approach to the use of symbols and metaphors, his inventive experimentation with language, time and space, and his unique awareness of sequence and identity have made his work fascinating to critics and readers. His honors include the Mehregan Award for the best Iranian children’s novel of 2004, the 1998 Golden Tablet Award for best fiction in Iran during the previous two decades, and Best Film Critique at the 1994 Press Festival in Tehran. Mandanipour is the author of nine volumes of fiction, one nonfiction book, and more than 100 essays in literary theory, literature and art criticism, creative writing, censorship, and social commentary. From 1999 until 2007, he was Editor-in-Chief of Asr-e Panjshanbeh (Thursday Evening), a monthly literary journal published in Shiraz that after 9 years of publishing was banned. Some of his short stories and essays have been published in anthologies such as Strange Times, My Dear: The PEN Anthology of Contemporary Iranian Fiction and Sohrab’s Wars: Counter Discourses of Contemporary Persian Fiction: A Collection of Short Stories and a Film Script; and in journals such as The Kenyon Review, The Literary Review, and Virginia Quarterly Review. Short works have been published in France, Germany, Denmark, and in languages such Arabic, Turkish, and Kurdish. Mandanipour’s first novel to appear in English, Censoring an Iranian Love Story (translated by Sara Khalili and published by Knopf in 2009) was very well received (Los Angeles Times, Guardian, New York Times, etc.). Censoring an Iranian Love Story was named by the New Yorker one of the reviewers’ favorites of 2009, by the Cornell Daily Sun as Best Book of the Year for 2009, and by NPR as one of the best debut novels of the year; it was awarded (Greek ed.) the Athens Prize for Literature for 2011. The novel has been translated and published in 11 other languages and in 13 countries throughout the world.