The Poet & the Fiddler: A Musing on Seamus Heaney

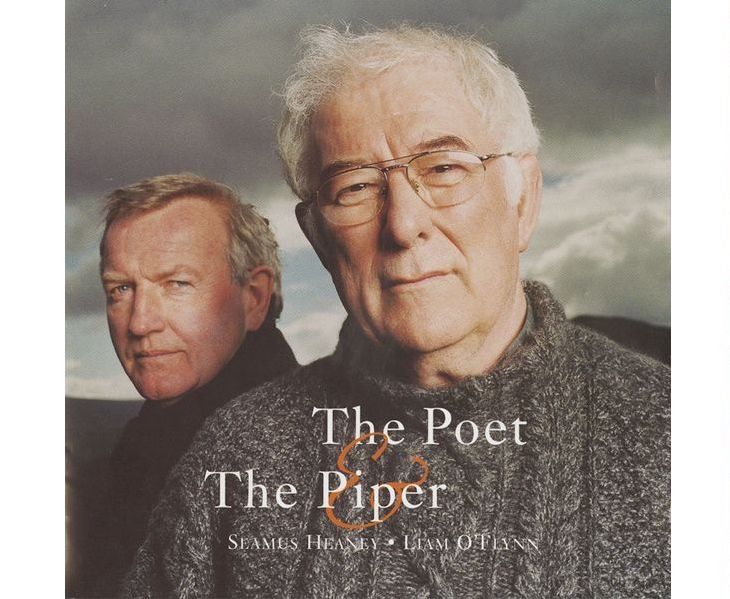

This morning, I cued up the first cut of The Poet & the Piper, an album released on CD by Claddagh Records in 2003 that featured a conversation—poetic and musical—between Nobel Laureate Seamus Heaney and eminent uilleann piper Liam O’Flynn (a founding member of the legendary Irish folk and traditional supergroup Planxty). Comprising readings of 17 poems by Heaney interspersed with instrumental complements on the pipes or on tin whistle by O’Flynn, the album in its entirety makes for pleasurable listening. But with the tenth anniversary of Heaney’s sudden and all-too-early death looming on August 30th, I wanted to pay particular attention to that first cut, his reading of “The Given Note,” a poem published in his second volume, Door Into the Dark, in 1969. Specifically, I wanted to see if, hearing him read it and O’Flynn respond to it (the only direct segue on the album), I could glean why, of all the possibilities in his vast body of work, that slight and relatively early lyric was chosen to be the sole poem read at his funeral mass, held in Sacred Heart Church in Donnybrook on Dublin’s south side on September 2nd of 2013.

Obviously, countless other Heaney poems might have been appropriate for the occasion—many of them much better known. His signature poem “Digging,” for example, with its predictive metaphor: “Between my finger and my thumb / The squat pen rests. / I’ll dig with it.” Or “The Harvest Bow,” with its elegantly burnished lines and its finely slant-rhymed stanzas. Or “The Skylight” from his sonnet sequence “Glanmore Revisited”: “when the slates came off, extravagant / Sky entered and held surprise wide open.” Or the wonderful imagining of—and in— “St Kevin and the Blackbird,” which Heaney draws attention to in his Nobel address “Crediting Poetry.” Or “Postscript,” which, recalling a windy drive in the west of Ireland, invites the reader to be pervious to the “big soft buffetings” that can “catch the heart off guard and blow it open.” Or perhaps “The Gravel Walks,” whose closing stanza yields the phrase that would be inscribed on the poet’s permanent gravestone two years after his interment in St. Mary’s cemetery in Bellaghy in south County Derry: “walk on air against your better judgement.”

But who am I to second-guess either the great man or his family? Presumably, given that Heaney had experienced some serious health issues several years before his death, he had shared with his loved ones some wishes regarding his eventual funeral.

In any case, “The Given Note” is an intriguing choice for several reasons. One is that its setting on the Blasket Islands, an archipelago off the coast of County Kerry in the far southwest, is pretty much the furthest point in Ireland from Heaney’s home county of Derry in Northern Ireland, an area which he wrote richly into his poems from the very start of his career until the end. It is also far removed in a different way: unlike the great majority of Heaney’s poems, “The Given Note” is based not on personal experience or observation but on a secondhand (or thirdhand) anecdote. In that regard, even as an ars poetica, which it ultimately is, it differs conspicuously from his similarly-themed poems that are contemporaneous with it yet whose metaphors of poetic creativity are grounded in the immediacy of his intimately “known world” of Irish farm life: “Churning Day,” “The Diviner,” “Personal Helicon,” “The Forge,” “Thatcher,” and others.

The anecdote at the heart of the poem is intriguing in its own right. One version of the story has it that at some point in time—probably before the government-assisted permanent evacuation of the Blaskets, completed in 1954—a fiddler from one of the islands heard a haunting melody while out fishing on the ocean and by playing along with it managed to capture its essence. In another version, an elderly couple heard the melody and memorized it. Latter-day speculation allows that the mysterious music may have come from humpback whales migrating to their breeding waters. Regardless, in Heaney’s poem a fiddler “brought back the whole thing” . . . a plaintive air in loose 3/4 time that came to be known as “Port na bPucaí” (“Music of the Fairies”). While in some tellings the fiddler is identified as one Muiris Ó Dálaigh, the earliest known taping of the tune dates to 1968, a field recording made of Seán Cheist Ó Catháin, who was born on An Blascaod Mór, the Great Blasket.

Eventually the anecdote (and presumably the tune itself) made its way to Heaney, and from the evidence of the resulting poem, it seems to have appealed to his interest in the wonder of the creative process, the question of how a work of art—in this instance a musical composition as a stand-in for a poem—comes into being:

So whether he calls it spirit music

Or not, I don’t care. He took it

Out of wind off mid-Atlantic.

Still he maintains, from nowhere.

It comes off the bow gravely,

Rephrases itself into the air.

In that regard, is it just coincidence that the poem’s title—“The Given Note”—resonates with Heaney’s musings in “The Makings of a Music: Reflections on Wordsworth and Yeats,” a lecture he delivered in 1978 that engages with the “two kinds of poetic lines, les vers donnés and les vers calculés” identified by Paul Valéry? He remarks: “The given line, the phrase or cadence which haunts the ear and the eager parts of the mind, this is the tuning fork to which the whole music of the poem is orchestrated, that out of which the overall melodies are worked for or calculated.” Describing further how “the quality of the music in the finished poem has to do with the way the poet proceeds to respond to his donné,” Heaney essentially admits to his own Wordsworthian tendency to surrender to “the given,” to allow himself “to be carried by its initial rhythmic suggestiveness, to become somnambulist after its invitations.” Its sonic texture comprising mostly slant-rhymes on the first and third lines of six tercets of variable line lengths, “The Given Note,” as read by Heaney on The Poet & the Piper, proceeds with the same rubato feeling that characterizes Liam O’Flynn’s playing of “Port na bPucaí” that follows it; indeed, metaphorically, the poem too “comes off the bow gravely, / Rephrases itself into the air.”

Yet, even while appreciating “The Given Note” as an ars poetica both thematically and stylistically, a reader might still be inclined to ponder its selection as the single poem read at Heaney’s funeral were it not for what seems, at first glance, to be Heaney’s exercising of poetic license by locating the fiddler not in a leather-hulled curragh in the North Atlantic, but indoors:

On the most westerly Blasket

In a dry-stone hut

He got this air out of the night.

Strange noises were heard

By others who followed, bits of a tune

Coming in on loud weather

Though nothing like melody.

He blamed their fingers and ear

As unpractised, their fiddling easy

For he had gone alone into the island

And brought back the whole thing.

The house throbbed like his full violin.

Some scholars have proposed that Heaney first heard the anecdote about the Blasket fiddler from renowned Irish composer and arranger Sean Ó Riada, whom he met in 1968 and for whom he wrote a poem in memoriam included in his volume Field Work (1979). Ó Riada, whose legacy includes the arranging of Irish traditional music for ensembles in the style made globally popular by The Chieftains, died young in 1971; but in 2014, Gael-Linn released a recording of his performing “Port na bPucaí” on solo piano, so the tune was clearly in his repertoire around the time that he and Heaney had some social interaction. In fact, Ó Riada may have heard that field recording made in 1968. So it is plausible that he was Heaney’s source.

One way or the other, whatever version of the anecdote he may have heard, “The Given Note” itself offers evidence that Heaney took the initiative to trace the story to its telling in linguist Robin Flower’s 1944 memoir The Western Island or the Great Blasket. Though locating the tale of the fiddler not on “the most westerly” of the Blaskets, which is Tearaght Island (An Tiaracht), but on Inishvickillane (Inis Mhic Uileáin), which Flower spells Inisicíleáin, his narrative nonetheless seems clearly to underpin Heaney’s poem:

In the old days, when this island was inhabited, a man sat alone one night in his house, soothing his loneliness with a fiddle. He was playing, no doubt, the favourite music of the country-side, jigs and reels and hornpipes, the hurrying tunes that would put light heels on the feet of the dead. But, as he played, he heard another music without, going over the roof in the air. It passed away to the cliffs and returned again, a wandering air wailing in repeated phrases, till at last it had become familiar in his mind, and he took up the fallen bow, and drawing it across the strings followed note by note the lamenting voices as they passed above him. Ever since, that tune, port na bpúcaí, ‘the fairy music,’ has remained with his family, skilled musicians all, and, if you hear it played by a fiddler of that race, you will know the secret of Inisicíleáin.

But that is not all. Explaining that “the music that went over the house on the island that night was a lament for one of the fairy host that had died and was carried to this island for burial,” Flower concludes his account with an interpretation of the episode that certainly rings true to the enormous sense of loss experienced—and expressed literally worldwide—by Seamus Heaney’s legion of readers and admirers in the immediate wake of his death ten years ago: “That fairy music, played upon an island fiddle, is a lament for a whole world of imaginations banished irrevocably now, but still faintly visible in the afterglow of a sunken sun.” While that interpretation is neither explicit nor implicit in “The Given Note,” its mournful spirit would certainly have been in the air when the poem was read at Heaney’s funeral. And like the droning undertones of Liam O’Flynn’s uilleann pipes or the slow bowing of the countless fiddlers who have likewise been drawn to the mysterious calling of “Port na bPucaí,” it continues to reverberate a decade later.

Thomas O’Grady was born and grew up on Prince Edward Island. He retired in December of 2019 after 35½ years as Director of Irish Studies at the University of Massachusetts Boston, where he was also Professor of English and a member of the Creative Writing faculty. His articles, essays, and reviews on literary and cultural matters have been published in a wide variety of scholarly journals and general-interest magazines, and his poems and short fiction have been published in literary journals and magazines on both sides of the U.S.-Canada border and on both sides of the Atlantic. His two books of poems — What Really Matters and Delivering the News — were published in the Hugh MacLennan Poetry Series by McGill-Queen’s University Press. He is currently Scholar-in-Residence at Saint Mary’s College in Notre Dame, Indiana.