To Claudia Rankine

February 28, 2021

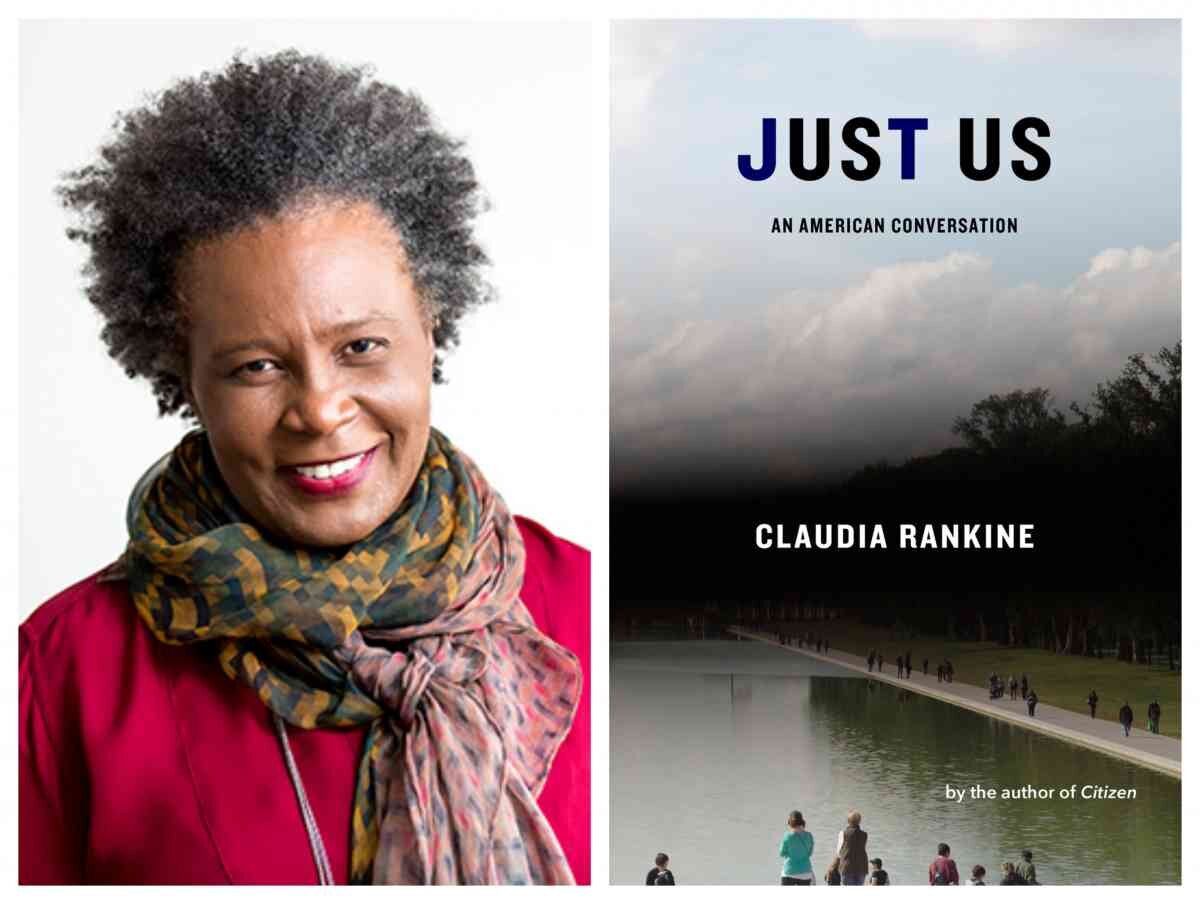

Today is the day he died. Snow is on the ground as it was then, the brown leaves of the elms are curled in every cranny, and the silence of Cambridge is greater than usual thanks to the virus that has covered the world. I have just finished reading the book JUST US by Claudia Rankine, a book about the insidious venom of racism in America. In this case, it is the blood-substance of it practiced in the educated and upper-echelon people, not so much the workers or servers.

The timely arrival of this book into my life showed me that it was being written while I was at home assembling related papers, months thumbing through folders of my father’s materials, something I had avoided out of a primitive disgust with ancestry. It was an opportunity to be fortified by the work that Claudia Rankine has done, knowing that these thoughts and histories will continue to agitate the underbelly of the White historical body. They have been scratching away for decades already, and are more irritating the longer they take to locate.

Thank you, Claudia, for the time you put into your useful book — useful for teachers to pass along to their students, and for regular readers, for the incarcerated and the free. Laid out in careful categories with footnotes and photographs to anchor the stories and essays down, it is a model of generosity to those who might not know “what’s up.”

Your book is, like mine, circled by social fear, something that made both of us poets, I think. But you have reined yours in and only your questions, many of them, percolate up from under. Yours is a book of questions and the most poignant one is too much to ask: Why? This is the question that all people cry out when they are being pulverized. And when a prosecutor is building a case, she must be asking herself the same question for the jury. Why?

Because of the mystery of repetition, I only wanted to know why, when slavery formally ended, it went on, both internationally and especially in the American court system.

I turned to the papers on law, the constitution, civil liberties, and civil rights, coming to the conclusion that younger legal historians would be better at research and interpretation than I would ever be, but I still dived into my father’s papers and talks, into his personal letters written before, during, and after WW2, to take a more experimental approach.

My interest has come too late and my ignorance is too great to do justice to scholars’ years of study. It was like trying to do an autopsy on the unconscious, the evidence being what was not revealed. Only the stuff around it. History. Nature. Voices. In the end I always turn back to the heartbeat of poetry that is healthiest when it is irregular.

Now let me tell you, Daddy, I had three children you never met, they had their own six who added up to nine among us. The three of mine have self-identified as Black and each of them could have had a different mother. The oldest is an ex-pat and writer who left this country when she was 20. The middle child is a writer whose main subject is race. And their brother is a graphic artist who draws cartoons of Americans who are part-human and part-animal. Their father and I divorced seven years into the marriage and now we never speak to each other. None of my children married someone White, and I never married again.

_______________

Fanny Howe is the author of more than thirty works of poetry and prose, including Love and I, The Needle's Eye, Come and See, and The Winter Sun. Howe was the recipient of the 2009 Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize. She also won the 2001 Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize for her Selected Poems, and has won awards from the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Poetry Foundation, the California Council for the Arts, and the Village Voice.