Rhyme and Reason

To write poems requires learning rhyme as well as reason (poetry and prose), becoming naturalized in poetry’s way of thinking, of comprehending the world, not just the grind, the grist of the logic of argument. Yeats achieved a supreme music, but equally important to his work, to what he taught by admonition and example, is his way of ending a poem with an image, not a statement, no peroration summarizing the case he’s made, no last line of a mathematical proof, signing off with logic’s monogram, QED. A statement can always be debated, contradicted, defeated. You can’t contradict an image or a song; you can’t be argued down if you end in apostrophe or revelation: “O sea-starved, hungry sea.” Or, most famously, here, roused in the final line by those three cretics that rock it from its cradle,

There’s a wisdom in ending with that image and in a question, but Shakespeare banks on a different flight song, crossing the finish line of Sonnet 29 “When in disgrace with Fortune and men’s eyes”:

Yet in these thoughts myself almost despising,

Haply I think on thee, and then my state,

Like to the lark at break of day arising

From sullen earth, sings hymns at heaven’s gate;

For thy sweet love rememb’red such wealth brings

That then I scorn to change my state with kings.

The order of the phrasing is crucial here. At its first “arising,” Shakespeare doesn’t spend his breath lifting the bird further; rather, he presses it back down into its humble origin in “sullen earth” (the skylark builds its nest not aloft in a tree but in a hollow in the ground) — loading the spring that launches both the skylark’s famous soaring vertical display flight and its equally rare and renowned song sung while on the wing. He makes his mark, hits his height of pitch with that lark singing “hymns at heaven’s gate.” There’s no up to go to from here; kings are beneath him. The couplet is meant to be banal, summarizing, returning him to earth.

For the needs of one of her own poems, Elizabeth Bishop bettered that ending with a quiet refinement. “The Fish” begins simply “I caught a tremendous fish” — none of the coy coaxing of meaning freshwater poet-anglers love to engage in, feathering their flies and looping gossamer casts over the puddle-pages of Roget’s Thesaurus. It’s plain language that catches the moment when the intensity of the simple act of looking, of seeing what’s in front of her (another, separate being who doesn’t return her stare) turns into vision. One suspects some visionaries see themselves as realists; this one writes with a naturalist’s customary care, a delicacy of attention that makes precision the measure of — is it love or a sense of justice that moves Bishop to get the world right? and makes her poems equal to the world — or at least those parts of the world — they capture in her proprietary blend of Wittgenstein (“Die Welt zerfällt in Tatsachen”) and Patsy Cline (“I fall to pieces over you”).

I looked into his eyes

which were far larger than mine

but shallower, and yellowed,

the irises backed and packed

with tarnished tinfoil

seen through the lenses

of old scratched isinglass.

They shifted a little, but not

to return my stare.

—It was more like the tipping

of an object toward the light.

Bishop often revises her poems on the fly (“It was more like the tipping…”), incorporating her senses’ ongoing updating of her consciousness in the artifact of the poem; here, revision sometimes means literally taking a second, closer look, correcting expectation by deeper exposure to things as they are. The poem continues:

I admired his sullen face,

the mechanism of his jaw,

and then I saw

that from his lower lip

—if you could call it a lip—

grim, wet, and weaponlike,

hung five old pieces of fish-line,

or four and a wire leader

with the swivel still attached,

with all their five big hooks

grown firmly in his mouth.

(italics are mine, added for emphasis)

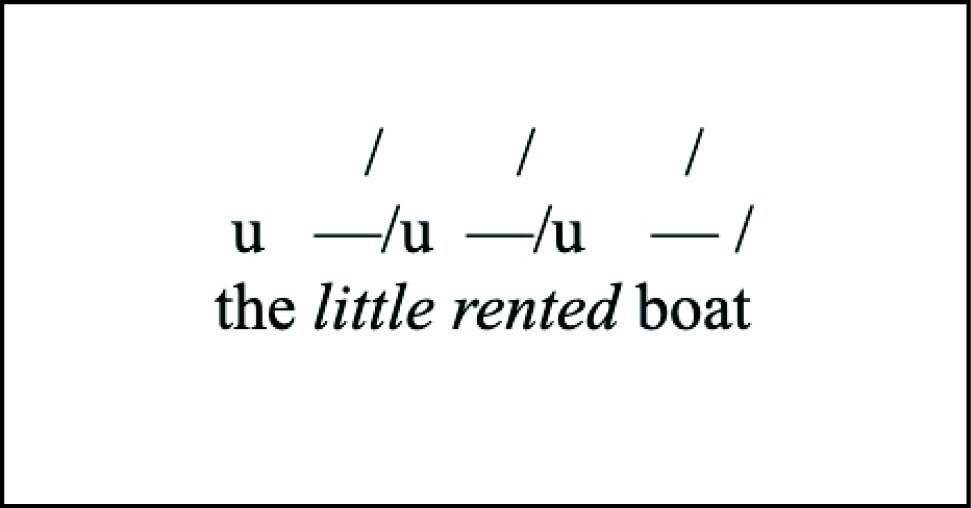

Plain language, here in short, mostly three-beat lines; with wisps of slant rhyme reduced in some cases to the merest consonance of the final sound of the line (boat/fight/ weight; all/venerable; there/wallpaper; down/in/oxygen; gills/entrails) — so inconspicuous as to seem a mere accident of accurate observation, yet such slight ligatures of sound help mesh the poem that lifts her fish into view. An attentive reader might ask the old question, which is more essential to a net, the strings or the spaces between? (The word “mesh” itself means both the spaces and the strings.) The warp and weft of Bishop’s lines are so deftly strung they seem airy, watery, nothing but flow — the opposite of tendentious rhetoric telegraphing its path to a grand finale. The underlying loose iambic meter makes itself felt, but its insistence is softened by ample variation in line length, anapaestic substitution, the presence of several disyllabic words that are trochees in themselves but fit perfectly into the iambic pattern:

and with many feminine line endings as well:

All lines are composed of phrases that would be at home in prose or in spoken conversation. Her detailed catalog of the fish continues, minutely describing those “five old pieces of fish-line,/ or four and a wire leader,” one of them:

. . . a fine black thread

still crimped from the strain and snap

when it broke and he got away.

Like medals with their ribbons

frayed and wavering,

a five-haired beard of wisdom

trailing from his aching jaw.

This is equal to Hopkins’s ocular resolution of inscape (“A windpuff-bonnet of fawn-froth/Turns and twindles over the broth/Of a pool so pitchblack…”) set in an entirely different key — major, perhaps, for Bishop, yet for Hopkins it would barely amount to wetting the reed and running chromatic scales as an embouchure warm-up for the audio/sonic pyrotechnics of instress yet to come. (In class, Bishop remarked that Hopkins “may have been the best poet of the nineteenth century.”) Only a tailor or a fishing-derby gumshoe would focus such forensic attention on that “fine black thread” — a single strand in the “five-haired beard of wisdom” (ironic wisdom!) he’s paid for with “his aching jaw.”

Two final sentences follow:

I stared and stared

and victory filled up

the little rented boat,

from the pool of bilge

where oil had spread a rainbow

around the rusted engine

to the bailer rusted orange,

the sun-cracked thwarts,

the oarlocks on their strings,

the gunnels—until everything

was rainbow, rainbow, rainbow!

And I let the fish go.

Here, the moment of vision is a revelation that suffuses, unifies, everything in sight, starting from a film of oil on the pool of bilge, spreading outward in waves or rings:

. . . until everything

was rainbow, rainbow, rainbow!

The only adequate response is to point at, not paint but name, repeat the name of the phenomenon — “rainbow, rainbow, rainbow!” — whose other (unsaid, scientific) name is “glory.” In these three iterations separated by pauses, you feel the pulsing surge as the oily spectrum widens, possibly to the beat of the engine, though the rhythm of stresses comes closer to the lub-dub systole-diastole of the heart. Eleven lines to describe how “victory” filled the boat. All that’s left for the speaker now is to do what this moment requires of her: to perfect, complete the action that has transformed everything to rainbow, and so perfect, complete the event of the poem. She takes one line to accomplish this. Bishop doesn’t write “I let the fish go” — that would be placing too much emphasis on the “I,” bragging, vaunting her own goodness. Nor does she bury that “I.” Modest as Herbert, down to earth as Donne, Bishop celebrates a communion that is as homely as it is holy, and still requires the full presence of two unique individuals in all their unlikeness. Bishop’s final line, the poem’s final sentence, comprises six monosyllabic words, receiving four, not three stresses as she read it aloud — not an anacrusis, the silent lifting of the conductor’s baton before the downstroke on the note, in which she herself would be elided:

That small word “And” means what follows flows inevitably from what transpired before. The action slides quietly, smoothly to its completion on the chrism of engine oil which spreads the rainbow that her word “And” has just brushed against. Note that, though it joins an unaccented with an accented syllable (not a ringing cymbal strike), the rhyme on “rainbow”/“go” is one of only two full rhymes in the poem (along with “saw” and “jaw”). That is, unless you count as rhyme two instances of the exact repetition of the line-ending words “wallpaper” and “lip.” Either way, these may seem artless or counter-artful, a slight awkwardness occasioned by — and so a guarantor of — her dedication to factual accuracy over the formal requirements of making a poem. Bishop’s practice harmonizes with Conrad’s expression of his aim in writing: “It is, before all, to make you see.” Her clarity re-buffs its Latin root — it’s not merely clear or transparent, it shines, such that it becomes, for this reader at least, a source of light.

In another poem with similar plain diction, trochaic words, and feminine line endings, but with both regular rhyme and a more regular iambic meter suiting its songlike nature, Bishop leans closer to Yeats’s conclusion in “The Second Coming”: she saves the deepest cut for last in “Insomnia,” a poem that knows how the heart compounds with fracture and breakage, shows what a little mirrored moonlight can do — to one abandoned, as Bishop has been, to self-reflection; devastating magic, but magic nonetheless, turning loss to song, straightforward day into opposite-night:

The moon in the bureau mirror

looks out a million miles

(and perhaps with pride, at herself,

but she never, never smiles)

far and away beyond sleep, or

perhaps she’s a daytime sleeper.

By the Universe deserted,

she’d tell it to go to hell,

and she’d find a body of water,

or a mirror, on which to dwell.

So wrap up care in a cobweb

and drop it down the well

into that world inverted

where left is always right,

where the shadows are really the body,

where we stay awake all night,

where the heavens are shallow as the sea

is now deep, and you love me.

Has anyone ever found, when love is done, a better way not to say “you were the cosmos to me”? Perfection. There’s a very high percentage of that through all her work. Faced with which, Jonson might have been less of a blotter and more of a sponge, to soak up these poems — and Jonson knew a thing or two about perfection in a lyric.

Reviewing her Complete Poems on publication in 1969, John Ashbery called Bishop “a writer’s writer’s writer,” which might sound like his Englishing of trop recherché for the common reader. Turns out her poetry, so featly footed, also has legs. Now her influence and acclaim are almost universally embraced. Her contemporary Robert Lowell in his lifetime was most widely celebrated, upheld for decades by the academy at the pinnacle of the pantheon. Who reads Lowell today? Are these two poets always to be, as Lowell wrote of himself and his third wife, “one up, the other down,/ . . . seesaw inseparables”? I’m not going to address the reasons behind such shifts in popular taste and critical assessment. Bishop and Lowell were friends who saw each other as first among peers. I trust we’ll catch up to their reciprocal enjoyment and respect. In the meantime, I offer the following notes as a cordial corrective — as one might “correct” coffee with a shot or two of ample proof.

Bishop can make her poems, especially the ballads and songs, seem like pure gifts, but I want to honor her hard-won ease and ‘artlessness’ — a stylistic achievement of the highest order — as I set them next to Lowell’s early frontal attack on Parnassus, as well as his later breaking and remaking of the lyre, twice — or thrice, if you find as I do a new style in Day by Day and neither, as Heaney saw it, a re-emergence of his second style, the free verse stanzas of Life Studies (refined through For the Union Dead and among the rhymed and metered poems of Near the Ocean) nor what Walcott described as a modification of his third style, “the Notebooks truncated,” but rather a synthesis of those two styles, different from both. As Lowell suffered and wrote through multiple breakdowns and breakups, he remained a knowing and self-knowing maker who, in the final, title poem of Dolphin — the last of five volumes of (mostly) “blank” or unrhymed sonnets — claimed:

My Dolphin, you only guide me by surprise,

captive as Racine, the man of craft,

drawn through his maze of iron composition

by the incomparable wandering voice of Phèdre.

. . .

[I have] plotted perhaps too freely with my life,

not avoiding injury to others,

not avoiding injury to myself—

to ask compassion . . . this book, half fiction,

an eelnet made by man for the eel fighting—

my eyes have seen what my hand did.

That last line reverberates as boast and confession of regret.

Lowell here consciously plays off — and twists — a line from Heminge and Condell’s introduction to the First Folio of Shakespeare: “His mind and hand went together.” Shakespeare’s two colleagues intended nothing but tribute to their friend’s felicitous facility with words; their praise continues, “And what he thought, he vttered with that easinesse, that wee haue scarse receiued from him a blot in his papers” — meaning of course Shakespeare hardly ever deleted a word. To which Ben Jonson famously responded “Would he had blotted a thousand.” In terms of the practice of revision, Lowell clearly stood squarely in Jonson’s camp. [So much so that in “North Haven,” her moving elegy for Lowell, Bishop wrote: “You can’t derange, or re-arrange,/your poems again.”] But far beyond that, in his rewriting of this line, Lowell implicates himself as a man of craft, guile, cunning, a planner-plotter-executor — close in spirit to the “many-minded” Ulysses, subject of the first poem of Lowell’s next, and final new collection, Day by Day, who conceived the trick of the Trojan horse that won the war, and then took ten years rushing home (from the ten years’ war) to the beloved wife he’d left behind — at least as close as he was to his craft-mate and guild-brother, the writer Racine.

One further twist: Lowell’s line also bounces off the adage: “Don’t let your left hand know what your right hand is doing.” Common usage may debase this to mean act first, think later of all the fallout of your doing. Even cheapened so, the echo calls up the origin of the saying and places Lowell well within the reach of Christ in his Sermon on the Mount: Don’t let your left hand know . . . “Give alms, do good deeds in secret and your Father in Heaven will reward you.” In Christ’s sermon, the reward, the gift just for listening, is immediately forthcoming: the form in which to pray, the words of the Pater Noster, including the resonant “Forgive us our trespasses.” Yet it’s pride, partly artistic, that stands in the way of Lowell’s asking for commiseration or forgiveness for the harm caused by his “plotting” — getting his life and the lives of those closest to him into poetry:

[I have] plotted perhaps too freely with my life,

not avoiding injury to others,

not avoiding injury to myself—

to ask compassion . . .

Whether in verse that can sometimes sound ringing as if moving in chain mail, or free verse that feels much more exposed, seemingly improvised a cappella, minus the meter and rhyme that primed him to thunder, Lowell can touch to the quick, be shockingly tender, electric, as a wound, as a lover, or both at the same moment, as here, from his second book, Lord Weary’s Castle, in “Falling Asleep over the Aeneid,” where an old man dreams he is Aeneas, beholding Pallas, dead. The scene opens luridly lit by flames and wings of flitting birds, martial and florid, more opera than Hollywood epic (except for the numbers of extras), Empire style, black and gold or bronze, all armor and char, draped then in feathers, more convulsive and weird than Virgil, closer to Flaubert’s Salammbo and The Temptation of St. Anthony. Pallas’s corpse is carried to the bird-priest,

. . . and as his birds foretold,

I greet the body, lip to lip. I hold

The sword that Dido used. It tries to speak,

A bird with Dido’s sworded breast. . . .

. . .

I groan a little. “Who am I, and why?”

It asks, a boy’s face, though its arrow-eye

Is working from its socket. “Brother, try,

O child of Aphrodite, try to die:

To die is life.” His harlots hang his bed

With feathers from his long-tailed birds. His head

Is yawning like a person. The plumes blow;

The beard and eyebrows ruffle. Face of snow,

You are the flower that country girls have caught,

A wild bee-pillaged honeysuckle brought

To the returning bridegroom—the design

Has not yet left it, and the petals shine [.]

“Life Studies,” the fourth section in his book of that title, is a series of family portraits (and one searing persona-poem from a wife’s point of view), the majority of which are written in free verse, a new departure, while the rest employ occasional rhyme. These photographic subjects are profiled against a composed backdrop; not random snapshots, they capture, freeze-frame, the hieratic moment, a second welcome advance as an approach to his material after — and in addition to — the headlong drive of Lord Weary’s Castle and The Mills of the Kavanaughs, where the verses can keep turning and churning whatever the obstacle, yet these poems are static, heraldic compared to the greater freedom and offhand ease he was to find in For the Union Dead, where the subjects feel much less posed, more caught in the act. And caught in the present (if not in the flux of the sonnets to come), where Life Studies seems more drawn from memory — perhaps starved to a card-deck of images by an heirloom album of photographs — than from a live model. One task Lowell took on in this section of Life Studies was to define himself amidst and against the clashing personalities of his elders. For anyone who thinks being scion of such illustrious ancestors is an unmitigated gift, look how out of place, unrelated, non-human, non-present, he sometimes feels. In these poems Lowell’s voice is most itself in the crystallizing act of self-identification:

I was five and a half.

I was a stuffed toucan . . .

I was Agrippina

in the Golden House of Nero. . .

I saw myself as a young newt . . .

We are all old timers,

each of us holds a locked razor.

I myself am hell;

nobody’s here— [.]

And most strikingly in “Fall 1961” from For the Union Dead:

I swim like a minnow

behind my studio window.

We are like a lot of wild

spiders crying together,

but without tears.

Lowell ascribed that last sentence-stanza to his daughter, in a poem that feels not just stuck in but spiked to the cross-hairs of the present tense by the aimed missiles of the Cuban Crisis and contemplation of the annihilation of the world in nuclear war. Motion is obsessive, repetitive, no breakthrough in sight (“we have talked our extinction to death”), while a decisive rash act might start the carnage. In a poem that begins and ends with the swinging of a pendulum, all the talk, diplomatic and otherwise, emptily resonates with the ticking of a clock:

Back and forth, back and forth

goes the tock, tock, tock,

of the orange, bland, ambassadorial

face of the moon on the grandfather clock.

(italics are mine, added for emphasis)

Yet somehow the poem rises to this height:

Our end drifts nearer,

the moon lifts,

radiant with terror.

Compared to such a devouring present, some poems in Life Studies reduce the present to a mere moment, a point from which to remember the past, as in “Grandparents”:

The farm’s my own!

Back there alone,

I keep indoors, and spoil another season.

…where Grandpa, dipping sugar for us both,

once spilled his demitasse.

His favorite ball, the number three,

still hides the coffee stain.

Never again

to walk there, chalk our cues,

insist on shooting for us both.

Grandpa! Have me, hold me, cherish me!

Tears smut my fingers…

Nothing now so rich; nothing equalling that feeling of being — or wanting to be — so closely wedded to another’s spirit. This is Lowell-Archimedes, finding in the present that spot on which to stand where his inspiration and craft are equal to the leverage needed to lift the past into available light.

In contrast to these collections, from Notebook 1967–68 through Dolphin, those five books of (mostly) blank verse sonnets are an attempt to catch the instant, whatever it contains; the figures can be revealed or all but abraded by the background, a welter of detail and motion.

Giving up rhyme means giving up quatrains and couplets (or octaves and sestets) so that the whole sonnet is a single stanza, one commodious room (which strangely makes the sonnet claustrophobic) to fill with the furniture, the mobili, all the change (not too high-toned to include “old undebased pre-Lyndon silver, no copper rubbing through”), the dailiness that is the diet of novels, siftings of history, stuff plucked from the news, quasi-gnomic quotations, accreted detritus, the moveable feast-or-famine of his life: image, detail snapped off and packed like match-heads in a pipe bomb. Having given up the timed detonation of the closing couplet’s rhyme, he’s counting on spontaneous combustion, the shock of small explosions all along the lines. The density can be exhausting, but the exceptions touch the transcendent, as in “Obit,” and in “Dolphin,” quoted above, in which Lowell catches the Dolphin who only “guides … by surprise” — rather, is caught by her; soon to be “blind with seeing,” he follows the tendril of “the incomparable, wandering voice” of his muse — into the new music of Day by Day.

Although he struck gold in many places and a few were honeycombed, leaving behind the tight cells of those blank sonnets he’d spent years remodeling is a tremendous breaking out of bonds — Lowell escaping the irons he’d put himself in by sailing directly into the headwinds of that form and those turbulent times. He loosens the tension on the strings of his lines, his lyre no longer tuned to concert pitch, yet the new book’s free verse is informed by the sonnets’ absorption in the moment, though such moments here are most often personal, domestic.

Having given up the plat and plotting of the sonnets, Lowell needs to find new ways to move these poems forward. Living in the present, staying in the moment, is no easier on the page than in life. The present is oppressive, a flow of moments, pure duration: something to get through. To live in it requires daring, a child’s genius for games, for improvisation (“catastrophes of description/ knowing when to stop, / when not to stop”), the courage to surrender everything to “sunshine that gave the day a scheme,” inspired, perhaps, by his young son, Sheridan, in whom Lowell saw himself as a child — both ghosted darkly in his memory of a lost photographic negative:

he, I, you

chockablock, one stamp

like mother’s wedding silver—

gnome, fish, brute cherubic force. (“For Sheridan”)

The poems are still a high-wire act, defying the gravity that makes them matter, but this new style is slack rope not tight rope, the harder art. Many of these poems open with a gambit that leads nowhere, peters out, or undoes itself, so the poem must begin again:

This golden summer,

this bountiful drought,

this crusting bread—

nothing in it is gold. (“This Golden Summer”)

This is akin to push-starting a car with a dead battery, listening for the moment to pop the clutch so the engine will catch. The new faith is that it will; the new mastery, that it does. The discontinuity of such openings argues that lifting the brush after the first stroke is as decisive an act as touching its tip to the blank canvas.

Here indeed, here for a moment,

here ended—that’s new.

Another new thing, your single wooden dice . . . (“Off Central Park”)

Some poems, as above, pick over the traces of the first stanza to find a way to continue.

Others find their conclusion in a new beginning:

This winter, I thought

I was created to be given away. (“Thanks Offering for Recovery”)

Questions (unanswered) abound; two of these poems begin thus; eight end so; two more do both.

“Endings” is most radical: it begins twice and ends three times, though a reader would be justified in finding that it opens with two endings and closes with three beginnings. In this book, when movement falters, and a verse paragraph ends, Lowell does not come back to the same thought, moment, image at a different angle; by the next stanza, he’s moved on, collaged in a clipping from a divergent area of his life, scenes juxtaposed but with their connections left unarticulated — rooms where he leaves the doors and windows open for the pleasure of that refreshment, the story not exhausted by being wholly told, puzzle pieces not slotted together, the picture unfinished, some blank white canvas showing through, the impression definite and dazzling.

The poem now has no design Lowell’s aiming to fulfill, beyond what association throws in his path, paralleling to a point what he had written in his “Afterthought” to Notebook 1967-68. These poems like those are “opportunist and inspired by impulse”; however, rather than “famished for human chances,” these poems have been fed a surfeit of them, as “Epilogue” discovers:

But sometimes everything I write

with the threadbare art of my eye

seems a snapshot,

lurid, rapid, garish, grouped,

heightened from life,

yet paralyzed by fact.

All’s misalliance.

Yet why not say what happened?

. . .

We are poor passing facts,

warned by that to give

each figure in the photograph

his living name.

Lowell no longer cares to rationalize, import (literary and historical allusions), or impart meaning. If, as he writes in “Shifting Colors,” “ nature is sundrunk with sex,” what is caught in flagrante delicto multiplying itself most promiscuously in this book is the figure (rhetorical!) of aposiopeses, or “interruptio” — a sudden break in thought or expression, a falling silent, signaled by a dash or an ellipsis. Seven first sentences in these poems end in ellipsis; the first stanza of two poems consists of a single line ending in a dash. Like the parataxis of vision, of revelation (which can be a mere pointing at, a nominal phrase with no main clause verb, the thing itself un-tensed, untouched by time), such a falling silent can be a recusal of the self from passing judgment; a refusal to subordinate some subjects, experiences, perceptions to others, thereby eschewing hierarchy; or a renunciation of articulating the relationships among things, including among the clauses of a sentence, the sequence of tenses, the sequence of events in time, before and after, cause and effect.

These apparently tentative beginnings and stray endings force a reader to review Lowell’s oeuvre and ask to what end he risked abandoning “those blessèd structures, plot and rhyme.” What could he not express through the old regimen of reason, the “click-shut” flourish of rhyme, and the hypotaxis or at least complete sentence structure which held together the straining early poems as well as the blank sonnets — even in those poems where he was seeking, as Heaney described them, “image or oracle over the logic of argument, revelation rather than demonstration”? What has been gained by this new plainness, directness? Consider Yeats’s poem “A Coat” that ends, “Song, let them take it/ For there’s more enterprise/ In walking naked.” Unvarnished exposure embodies Lowell more fully, humanly, “under the commitments of [the] flesh” — Ted Hughes’s phrase, but Lear on the heath is the best proof of the advancement of learning such mortification offers: immediacy, simplicity, fellowship with all living and suffering beings (think of all the animals that swim, crawl, fly, trot, waddle through Day by Day), an openness to heartbreak neither over- nor understated.

The new fact of extreme syntactical abruption in these poems contributes to the reader’s direct experience of misalliance, one of Lowell’s master tropes in this book. [A second is accretion, “the account/ accumulating layer and angle…/ 50 years of snapshots,/ the ladder of ripening likeness.// . . ./our rust the color of the chameleon.”] Misalliance: of things and thoughts broken off, unmatched, things ended but not completed, of open-endedness, “until the watch is taken from the wrist.” Once that stream has been crossed, or rather, once one sinks midstream, what waits on the far side of death? “The Day” offers this glimpse: “As if in the end,/ in the marriage with nothingness,/ we could ever escape/being absolutely safe.” All risk belongs to the living. These poems and the dramatic beats they contain, the progression from one to the next, are stepping stones, a target into (not across) the rushing stream of the present.

Now that the breathless packing of the blank verse sonnets is gone, the pause of the caesura is no longer the sole gap — possibly opening onto terror — to be raced over. [Recall Lowell’s translation of Baudelaire’s “Le gouffre”: “Pascal’s abyss went with him at his side,/ closer than blood—alas, activity,/ dreams, words, desire: all holes!”] Irregular short lines and short stanzas add up to more white space in the stanza breaks and at the ends of lines — more discontinuity, more possibility of lost connections, and the consequent terror. Yet the lines aren’t tensed, there’s a welcome ventilation as the rhythm of stanzas and the spaces between — movement and rest (words and rest) — delivers the rhythm of one of Lowell’s lived days. There is a new expansiveness, a wry gentleness, a generosity (even toward himself) related to a recent “second overflowing of Eros”:

Last summer nothing dared impede

the flow of the body’s thousand rivulets of welcome[.] (“The Downlook”)

Still, the book can be read as a catalog of losses: his marriage has failed, there’s no money for his wife (a Guinness heiress) to keep and run her house, she’s been forced to put it on the market; he’s sixty, and afraid his death is close (both his parents died at that age). He harbors no hope of eternal life; his faith is long gone:

The Queen of Heaven, I miss her,

we were divorced. (“Home”)

Such losses are given their full weight, which makes the countervailing generosity, fecundity, and fellowship all the greater. There’s a directness, an openness, alert and alerted to the world, whereby watching what happens can flare into momentary vision:

Things gone wrong

clothe summer

with goldleaf. (“Homecoming”)

Early on, such a quip might have called up Mephisto if not Satan the Prompter, and occasioned lines on our postlapsarian state; now his passage takes part in the order of the natural world. The soul’s journey that got him here had already begun and been acknowledged in his poem “Florence” from For the Union Dead:

The apple was more human there than here,

but it took a long time for the blinding

golden rind to mellow.

Such a long slow maturation shows in the savor of this new vintage, the feel of it on the tongue, in mouth and throat when spoken, along with its changed terroir; the soil and weather of these poems have an English-Irish softness — in stark contrast to flinty, granitic, Puritan New England, the tar and concrete “grind” of Manhattan, the outcroppings of schist in Central Park — which can give rise to breakthroughs of unheralded bliss, as in “The Downlook”:

Nothing lovelier than waking to find

another breathing body in my bed . . .

glowshadow halfcovered with dayclothes like my own,

caught in my arms.

And even here in “Last Walk?”:

The unhoped-for Irish sunspoiled April day

—where there’s something new in the coiling movement of the line, dapple and dazzle, ripple and flow accommodating eddies and crosscurrents—

heralded the day before

by corkscrews of the eternal

whirling snow that melts and dies.

That whirling snow made eternal in memory by how instantly it melts and dies. That’s the immortality he trusts now; for him, what other is there? “We took our paradise here—/how else love?”

The fertility of the ground beneath these poems is evident in the ease and verve of the compounding: “Glowshadow halfcovered in dayclothes like my own”; “The unhoped-for Irish sunspoiled April day” — despite the fact that this last walk ends Lowell’s seven years together with his third wife, Caroline Blackwood. But more than any geographical fact, the subsoil of these poems is age:

Sometimes

I catch my mind

circling for you with glazed eye—

my lost love hunting

your lost face. (“Homecoming”)

Age is the bilge

we cannot shake from the mop. (“Ulysses and Circe”)

After fifty,

the clock can’t stop . . .

our rust the color of the chameleon. (“Our Afterlife I”)

In Lowell’s case, age (he died, as he feared, at sixty) came with the attendant grace and ripened wisdom to enjoy whatever enjoyments remain.

I grow too merry,

when I stand in my nakedness to dress. (“Ten Minutes”)

Bright sun of my bright day,

I thank God for being alive—

a way of writing I once thought heartless. (“Logan Airport, Boston”)

There is a minatory echo in “Domesday Book” — the title refers to a survey conducted by an earlier (successful) would-be conqueror of England, a reckoning showing who held which fiefdoms from Harold, England’s king (felled “with an arrow in his eye at Hastings”) — Norman William’s guide to the efficient extraction of taxes. The first line of the poem reads like an epigraph: “Let nothing be done twice — ”. Yet the unspoken exhortation that reverberates throughout this book is “Let nothing be forgotten”:

Only today and just for this minute,

when the sunslant finds its true angle,

you can see yellow and pinkish leaves spangle

our gentle, fluffy tree—

suddenly the green summer is momentary . . . (“The Withdrawal”)

Your father died last month,

he is buried . . . not too deep to lie

alive like a feather

on the top of the mind. (“Burial”)

But we must notice—

we are designed for the moment. (“Notice”)

In “Grass Fires,” a poem about accidentally igniting a fire when, as a child, he tried “to smoke a rabbit from its hole” on the grounds of his grandfather’s house, the flames run from “flaps of frozen grass” to “fire everywhere,/…the tree grandfather planted…/combusting, towering/ over the house…/

My grandfather towered above me,

“You damned little fool,”

. . .

The fire engines deployed with stage bravado,

yet it was I put out the fire,

who slapped it to death with my scarred leather jacket.

I snuffed out the inextinguishable root,

I—

really I can do little,

as little now as then,

about the infernal fires—

I cannot blow out a match.

This is a miracle of capturing the dilations and shrinkages of memory over time, played over and against the changing scale of life as one passes from child to prime adulthood and beyond. But how does Lowell so loosely capture some sense of that burning tree as his family tree, his snuffing out something of his familial inheritance when he snuffs out the “inextinguishable” literal “root,” or how so simply turn the burning sods into “infernal fires”? That one word changes everything in a synapse, not just by alluding to Dante and Milton (and the Bible behind them), but effortlessly getting in, for readers who have followed him, so much of Lowell’s own personal and literary agon with Roman Catholicism, conscience, the Pilgrim and Puritan heritage of New England (he had ancestors on both sides of the divide, most famously the preacher and theologian Jonathan Edwards) — the material of his first three books — that dilation, that whole vision in Lowell’s heart and now in the reader’s head, in the next heartbeat — in the space of that em-dash following “fires,” pricked by that em-dash — imploding, collapsing back toward earth, age stooping toward the child it was, speaking the language it had:

“I cannot blow out a match.”

Was — is — such simplicity always available? Is the ripeness all? Can it only be arrived at after passing through hell? Remember Lear: “Pray you, undo this button.”

It’s the offhand line that touches the quick of life, a matter of placement and tone, a shift in scope from what came before, as below in the poem’s final verse after the blank space of a line drop in which everything halts for a moment, when even the heart pauses long enough to learn what it has lost:

The household comes to a stop—

you too, head bent,

inking, crossing out . . .frowning,

at times with a face open as a sunflower.

We are lucky to have done things as one. (“Shaving”)

Lowell’s final volume of new poems appeared just as he was readying to return from the island (Ireland, earlier England) of his exile and his failed third marriage, to Manhattan and his second wife, Elizabeth Hardwick, in what had been their home together. (He was to be discovered dead on arrival in the back of a taxi, when the meter stopped ticking.) Such dramatic late changes in domestic arrangements and literary style are rare. What reader of Lowell’s early work could have anticipated the series of changes along the way or, in particular, this last style? And how connected are they to, in his friend Robert Fitzgerald’s words, Lowell’s having been forced to “govern his greatness with his illness in mind”? Which of us knows the measure of courage, fortitude, and humility it must have taken, time after time, to stand up under the burden of guilt, hurt, heartbreak, and exhaustion his breakdowns caused, and begin again? To have found the grit needed seems an access of grace.

The title Day by Day recalls Prospero’s bittersweet farewell to the island of his exile and his promise, in the final act of The Tempest, to relate all the details of that years-long exile later, at his leisure: “for ’tis a chronicle of day by day.” Yet by Lowell’s logic this book is not a chronicle, since, as he reasoned in his “Afterthought” to Notebook 1967–68, “many events turn up, many others of equal or greater reality do not.” Still, these poems call up Prospero’s abjuration of “rough magic” (while speaking some of Shakespeare’s most masterly blank verse lines), his requiring “some heavenly music, which even now I do, to work mine end upon their senses that this airy charm is for.” For Lowell, all that’s left of heaven is the light:

Pray for the grace of accuracy

Vermeer gave to the sun’s illumination

stealing like the tide across a map

to his girl solid with yearning. (“Epilogue”)

Light blesses everything it touches, and requires of us that we see the world and our actions in it for what they are.

Arriving tandem each new day with the pain, with all the sorrow of a life, that benediction fills Day by Day.

And what of the resistance our lives put up to being caught, pinned down, turned into words? Lowell wrote: “My eyes flicker, the immortal/ is scraped unconsenting from the mortal.” To which I would add — with good reason, that resistance; and: in art, in poetry, as with an electric current and the tungsten filament in a light bulb, or with a meteor entering earth’s atmosphere, it’s the friction, the resistance, that makes it blaze.

Martin Edmunds' first book, The High Road to Taos, was chosen by Donald Hall for the National Poetry Series. His most recent book is Flame in a Stable (Arrowsmith Press, 2022). Martin’s work has appeared in The New Yorker, A Public Space, The Paris Review, Little Star, Grand Street, The Nation, The Partisan Review, Southwest Review, and Agni among other journals and anthologies; three poems are featured on the Yeats Society of NY website. Awards and honors include an Artist Fellowship in Poetry from the Massachusetts Cultural Council, the “Discovery”/ The Nation Prize, the Lloyd McKim Garrison Medal for Poetry, and the Harvard Monthly Prize. Edmunds was an Artist-in-Residence at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine for many years, where he wrote plays, verse plays, libretti, and entertainments. He has also co-written screenplays, including Passion in the Desert, a feature adaptation of the Balzac story for Roland Films released by Fine Line. Edmunds works as a freelance editor, teaches creative writing and versification, and digs life on the Outer Cape as a landscaper, clam raker, and oysterer.