How the Edward Said Library of Gaza Was Born

In May 2014, I took my last exam to obtain my Bachelor’s degree from the Islamic University of Gaza. I had majored in English-language teaching (“TEFL”). English literature was my main interest, though: my favorite course had been Romantic Literature.

In July, a week before our graduation ceremony, Israel attacked Gaza. On August 2, 2014, warplanes targeted my university’s administration building. By the end of the day, what had once been the English department lay beneath a heap of rubble. When I finally arrived at the site where I had spent hundreds of hours pouring over the works of Wordsworth, Blake, Dickens, T. S. Eliot, Orwell, and Arthur Miller, the sight of thousands of books buried under rubble, especially the English-language books for which I felt such an affinity (I’d been teaching English to 6th and 7th graders in Gaza’s UNRWA schools) struck me the hardest. Among the lost was The Norton Anthology of American Literature which, I later learned, a professor had used in preparing his lectures.

I worried about my exam papers as they might not have been graded yet. They too must have been buried with the books. I was even more concerned about the characters I’d analyzed for my final in English Literature in the Twentieth Century course. Winston Smith from Orwell’s 1984 was also buried beneath several tons of concrete. I felt particularly sad for him. Had he not suffered enough already at the hand of his creator? Was it possible that Julia had had a chance to make love with him, deadening the pain they both must have experienced from the attack?

Hemingway, Faulkner, Twain, Steinbeck, Fitzgerald, Walker, Mailer, and James (to name just a few) lay smothered in dust and forced to sleep in the dark. Drones buzzing in the sky must have had assaulted their ears. I wish I’d been able to brush the dust off their clothes; I was sorry I hadn’t been able to hug them during the bombings.

A few weeks before the attack on the university, my family home, where I lived along with my father, mother, and seven brothers and sisters, had been badly damaged by an F-16 missile. The Israeli army had targeted our neighbor’s house. Unfortunately, three of our rooms became collateral damage. The holes in the walls looked like gaping windows which, unfortunately, we were unable to close during the harsh winter that followed.

The blown-out walls remained open for ten months. My family was never paid, as promised by the UN or UNDP, to plug the holes. The winter of that year was merciless.

One of those rooms had contained my modest personal library. It had numbered about a dozen books, including The Call of the Wild, 1984, Death of a Salesman, Look Back in Anger, Macbeth, and Othello.

I kept my friends on Facebook informed about the situation in Gaza. I don’t know whether it was wise to have done that, but I was at the time volunteering to translate for some French, Italian, and Belgian journalists. It turned out to be dangerous work. I recall driving one afternoon on our way to east Gaza when a rocket exploded a few feet ahead of us. A funnel of black smoke rose from the ground. We all panicked. It was dark and the explosion had lit up the sky. Our car almost hit a pedestrian fleeing the scene.

On our way back to Jabalia Camp, to which my family had fled to escape the bombs, a truck with defective brakes nearly collided with our car. Luckily, the truck was moving slowly enough for us to veer out of the way. As I had been filming our journey, I have a record of our near miss on my cell phone.

I lost two close friends in that “war.”

The 2014 assault ended on August 26, making it the longest attack Gazans had thus far endured. When my graduation ceremony, which had been postponed for two months, finally took place, it had the air of a family reunion celebrated inside a ruin. We paused to remember the two dear friends and classmates we had lost to bombs. My friends, Ammar, who’d majored in Arabic literature, and Ezzat, who’d majored in information data analysis, were represented by their families. In lieu of diplomas, they were given framed portraits of their dead sons.

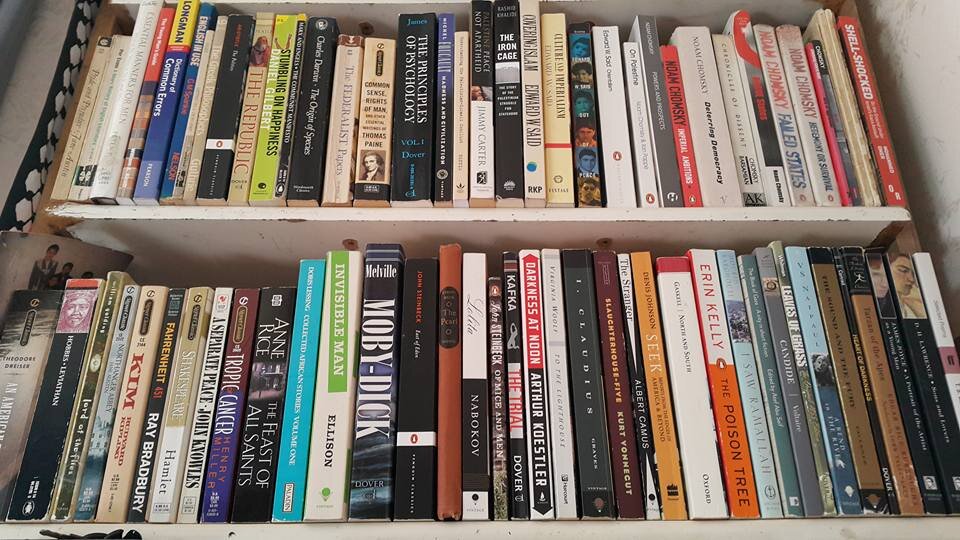

When they read many of my posts about our plight, some of my online friends congratulated me on surviving and sent several English books as gifts. These volumes became the embryos which eventually grew into the Edward Said Public Library of Beit Lahia City in northern Gaza. Today the library boasts a collection of 2,000 books in English and Arabic. This past October, a sister library opened in Gaza City.

In the process of building the library, books became my closest friends, offering wisdom, consolation, and hope, and writing itself became the air I breathe.

Mosab Abu Toha is a Palestinian poet, fiction writer, and essayist from Gaza. He is the founder of the Edward Said Public Library, and in 2019-2020 was a visiting poet and scholar at Harvard University. He gave talks and poetry readings at the University of Pennsylvania, Temple University, the University of Arizona (w/ Noam Chomsky), and the American Library Association conference. His work has appeared in Poetry, The Nation, Solstice, Arrowsmith, Progressive Librarian Guild, among others. Mosab is the author of Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear: Poems from Gaza, forthcoming from City Lights Books in April 2022.