Stravinsky at the End

In an interview published in the NYTimes in June of 1966, Igor Stravinsky, then the most famous composer in the western world, discussed the rigors of his prolonged and painful sicknesses. He said: “I suffer, too, as never before and as I have never admitted, from my musical isolation, being obliged to live now at a detached and strictly mind level of exchange with younger people who profess to wholly different belief systems. I am also, and for the first time in my life, bothered by a feeling of loneliness for my generation. All of my contemporaries are dead. It is not so much old friends or individuals, nevertheless, and certainly not the mentality of my generation, that I regret, but the background as a whole…”

Sometime later, I experienced what was undoubtedly the most fortunate of many memorable times in the concert hall. My father had been given tickets to the dress rehearsal and world premiere of Stravinsky’s Requiem Canticles. He knew I was far more interested than he in such things and kindly gave them to me. Stravinsky was a great presence in my life. His conversations with Robert Craft in the New York Review sparkled with a range of references and depth of experiences, shaping my sense of what an artist or a person active in the world could be.

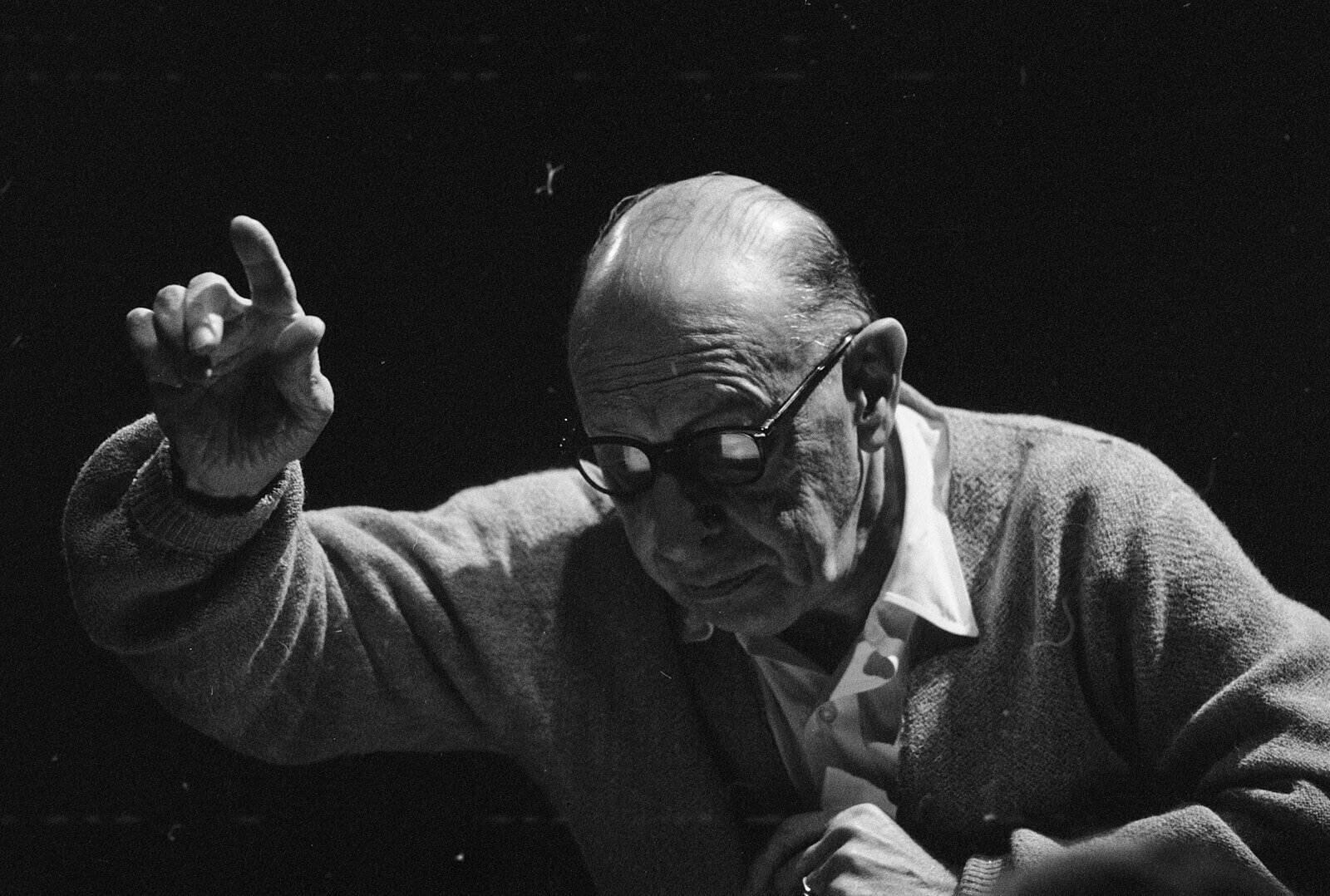

As I recall, the dress rehearsal took place at around 11 a.m. Except for the warmly lit stage, the large, boxy auditorium was dark and chilly. The ensemble and chorus were waiting on stage. The conductor, Robert Craft, Stravinsky’s assistant, friend and, in some ways, muse, had not yet arrived. Most of the music students and faculty were scattered in clumps throughout the hall. Because my musical education was limited, I felt quite shy so found a place out of view in a side balcony.

The acoustics there were not the best, but I could see Stravinsky, swathed in white scarf and tan overcoat, tiny, bald, and pale, frail like a newly hatched bird. His wife sat next to him on one side, on the other, an empty seat, then a man who frequently leaned over and commented as Stravinsky looked at the score lit by a stand-light on a table in front of him. The instrumentalists were arranging themselves, but there was perhaps less banter than there might have been. The people in the audience were almost silent. Everyone was very aware that this was most likely, as so it turned out to be, the composer’s last major piece. Stravinsky had had his first stroke ten years earlier, and although he had continued to compose and conduct, strokes continued to weaken him.

Robert Craft, self-effacing in gray suit, black horn-rimmed glasses, came in from the rear of the hall, walked to the front and sat with the Stravinsky and his wife, leaned past her to listen to the composer. There was an easy intimacy amongst them. The auditorium was silent as the two men talked quietly. Finally, Craft stepped up on stage, said a few things to the players, and the rehearsal began with the urgent plaintive strings in the opening section of the piece. I was aware of hearing something few had ever heard before and felt myself entering a new world.

Stravinsky’s frequently published conversations with Robert Craft were a stream of stories about the greatest artists, musicians, and writers of the 20th century, all of whom he had known, at least in passing, accounts of often quite recondite books, plays, operas, music, poetry, art works, and all seasoned with his acerbic repartee. As a conductor and sometimes lecturer, Stravinsky travelled constantly, and thus had met everyone of cultural significance everywhere. He could be amusing and cutting about all this. He was himself an intersection of many critical vectors in 20th century culture. It was hard to escape the sense that Stravinsky was not just the representative of one culture or another, but that he embodied culture itself. He was so dazzling and complete in this role, that it was easy to forget that he exemplified another aspect of 20th century life; he was always an exile.

He had been forced to leave Russia; his property, his bank accounts, and his copyrights had been confiscated. He had lived in many parts of Europe. He was forced to escape the Nazis in Paris, and seek shelter first in Los Angeles, then New York. Though there was really no time in which he was not one of the most famous people in the world, he had had to make a place for himself anew everywhere he went. He did not have the security of home ground. This also led to a reputation for being extremely mercenary, even if always witty. A friend who knew him well gave him, as a joke, a copy of the U.S.Tax Code for Christmas. He called a few days later to see what Stravinsky thought. In his thick accent, he murmured: “My Darling, I wept on every page.”

Beginning in his early 70s, and influenced by his new friend Craft, Stravinsky made a radical change in his compositional methods and began using serial composition techniques. This brought about a great rejuvenation in Stravinsky’s composing life. Many of the major pieces from this time were based on Christian and Hebrew liturgies, even if perhaps the best-known work from that time was Agon, written as a ballet for his friend, compatriot, and near contemporary, Georges Balanchine. This challenging, confrontational, and seductively strict piece marked a very different kind of Stravinsky. Balanchine’s highly abstract choreography changed the landscape of ballet. At this time, he also composed several pieces in memory of deceased friends and colleagues, “necrologies” as he called them. Stravinsky’s spirituality as well as his sense of loss were deep, and, except in his music, infrequently made public. All these pieces echoed the austere faith of an almost forgotten time. Perhaps his deep loneliness gave a particular urgency to create such vital linkages between his vanished world and the one in which he found himself. But it was also a deep devotion and unceasing love that drove him to continue, revealing new harmonies, rhythms, and resonances, illuminating the world from which soon he would depart.

The evening of the première, I was at the back under the balcony. Many famous composers, writers, intellectuals were there, but the person I remember was Robert Oppenheimer. He wore a tuxedo, was gaunt, his face very flushed and frozen in a kind of terrible anguish. He seemed so deeply pained that those who did not know and greet him, looked away. It had been widely reported that when he witnessed the first atom bomb test, Oppenheimer found a line from The Mahabharata surfacing in his mind: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” He had been essential in creating the most destructive weapon ever seen and looked like a man burned to the core.

The audience settled quickly and, after some other pieces which I no longer remember, Requiem Canticles began with the prelude, hushed, urgent strings, and unfolded through nine sections, with a great variety of rhythmic devices, melodic transformations, and combinations of instrumental and choral settings that made the relatively short but deeply moving work seem expansive and vast. It seemed to rise out of a distant darkness and carry us on the subliminal pulse of a hidden stream. Craft would later write about how Stravinsky had “discovered’ the musical material from which the piece evolved, and indeed it progresses with a kind of natural-seeming logic and vitality. Perhaps most striking for me, were the beginning, the end, and the “Libera Me” with the chorus singing and speaking simultaneously, somewhat in the manner Stravinsky used in his choral piece, Threni. But the essential feeling of the whole requiem, even with its many complex and subtle effects, was simplicity, as if at the center of every note, chord and phrase was a muted cry of loss. At the conclusion, the audience was silent, as had been requested in the program, but suddenly Oppenheimer leapt to his feet applauding. The audience quickly followed in a prolonged standing ovation. Later, I read that Oppenheimer had this piece played at his funeral.

Stravinsky wrote other pieces after Requiem Canticles, but they were short chamber works. Soon, he could no longer travel or conduct; even receiving guests became burdensome. So, it is remarkable and inspiring that being so ill, Stravinsky could still reach deeply into his being, his heritage, and his longing to produce this last great piece as well as those afterwards.

Stravinsky’s last works have a severe beauty that remains always haunting. Clearly, he knew he could not live much longer. The chords, their progressions, their movement forward resonate with an inner clarity, a deep stillness. Even just remembering them, it’s easy to imagine I’m in the cold vaulted nave of an abandoned Romanesque church, seated near a pale limestone column. There’s one melodic fragment, one sequence, one confluence of instruments and voices, one rhythm and then another. They shimmer in the still air. Each changes what went before. Feeling death stirring nearby, the future is void; the past and the present are luminous, momentary, continuous, completely new. There is so much. I am old, and, within this, cannot long remain.

It is, as near the end of his life, Bashō wrote: “The Moon and the Sun are eternal travelers. Even the years wander on. A lifetime adrift in a boat, or in old age, leading a tired horse into the years, every day is a journey, and the journey itself is home. From the earliest time, there have always been some who perished along the road.”

______________

This short reminiscence about Igor Stravinsky appears as a coda at the end of WINTER LIGHT, a book Douglas Penick has written about old age, the many kinds of losses it exacts, and the great range of unexpected openings it provides. WINTER LIGHT will be published by Punctum Books in September, 2024 and available both in print and digital formats.

Douglas Penick’s work appeared in Tricycle, Descant, New England Review, Parabola, Chicago Quarterly, Publishers Weekly, Agni, Kyoto Journal, Berfrois, 3AM, The Utne Reader, and Consequences, among others. He has written texts for operas (Munich Biennale, Santa Fe Opera), and, on a grant from the Witter Bynner Foundation, three separate episodes from the Gesar of Ling epic. His novel, Following The North Star was published by Publerati. Wakefield Press published his and Charles Ré’s translation of Pascal Quignard’s A Terrace In Rome. His book of essays, The Age of Waiting, which engages the atmospheres of ecological collapse, will be published in 2020 by Arrowsmith Press.