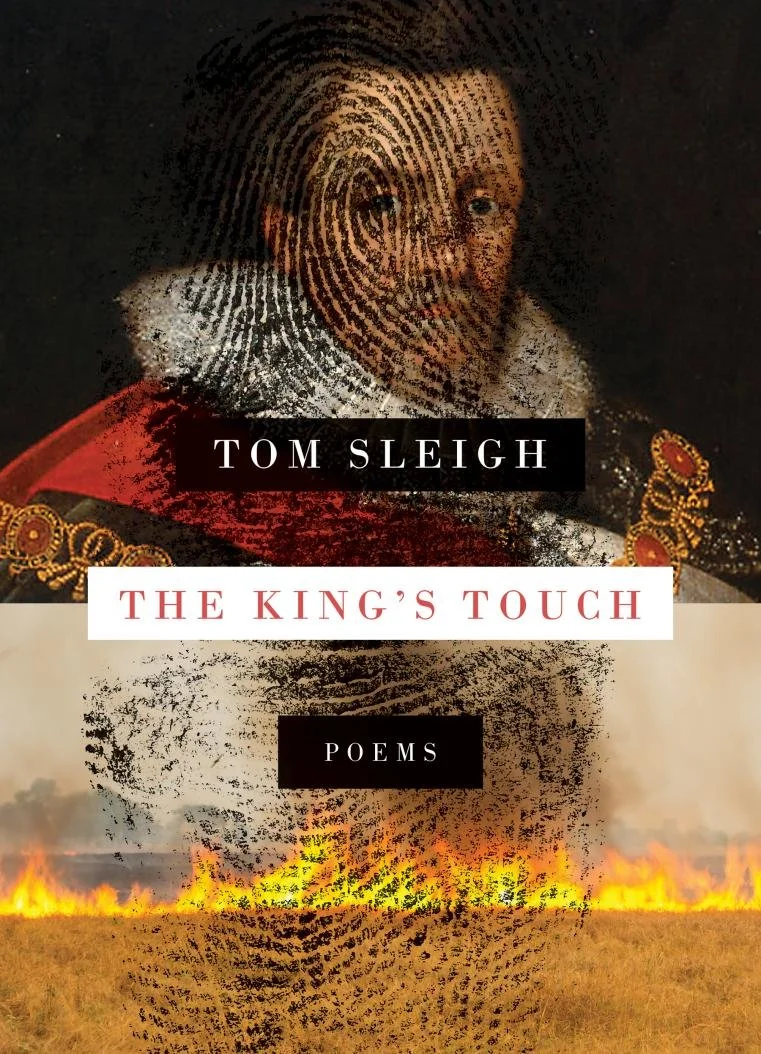

On Tom Sleigh’s “The King’s Touch”

The King’s Touch by Tom Sleigh

Graywolf Press, 2022

112 pp., $16.00

In his essay “The Lands Between Two Rivers,” Tom Sleigh describes the qualities of poems he loves: “Complexity of feeling, a style that embodies emotion, as opposed to riding on top of it with lots of verbal pyrotechnics and rhetorical display, a sense of the deep past resonating behind a line, and the feeling that the poet, as Seamus Heaney once said, aspires to make poetry an independent category of human consciousness, partaking of, but not beholden to, politics, religion, psychology, or sociology.” He’s writing in context of a 2014 trip to Iraq to talk about literature and creative writing workshops with Iraqi writers, professors, and students; he’s also learning how to fasten a bulletproof vest and what to do if his vehicle is under fire. It’s no surprise that Sleigh’s new book of poems, The King’s Touch, examines the bloody 21th century as a consequence of the bloody 20th. Throughout the book, the living converse continually with the dead through history, kinship, myth, and memory.

Sleigh has been writing about soldiers and refugees since 2007, calling his three previous collections “an unofficial poetic trilogy about war, refugees, and state violence.” These concerns continue to figure in The King’s Touch, along with the effects of age observed in loved ones (and oneself), the rigors of illness (including Covid), and possibilities for tenderness in the most harrowing situations.

The book’s first poem could function as a keystone for its five-part structure, configuring time and space in all its quantum mutability. “Youth” begins with twin boys playing in a war zone, chasing and laughing, “I’m gonna kill you!” Sleigh writes, “I’m supposed to be doing a story/on soldiers, what they do to keep from/being frightened,” but all he can think about is how he and his own twin yelled the same. “…Tim, who is so alive will one day not be: will it be me or him who dies first?” Sleigh observes the soldier “sitting/still inside himself, listening to his nerves” while recalling Achilles’ “immortal mother”: while keeping “the worms/from the wounds of his dead friend,” she knew “she wouldn’t be allowed/to keep those same worms from her son’s body.” How does one live with the knowledge of death without going crazy? Sleigh’s soldier cleans his rifle “for the second time in an hour” while shadows of the sweet-smelling pines, noted in the poems’ first line, “bury him and the little boys/…/in non-metaphorical, real-life darkness.”

“Youth” allows a handful of moments to comprehend time that spans the daily, the historical, the mythic and the personal. The pines’ shadows grow longer as history lobs its “teatime mortars;” the boys’ play trips both recollection and speculation on the future. The soldier, Sleigh’s assigned subject, repeats a ritual of protection, while a fragment from the Iliad assures that protection is impossible, even from a goddess. All of this is written mostly in words of one or two syllables, conversational in style and tone. The canny repetitions of “doing a story,” and “twin brother,” the alliterative “I”s keening in the poem’s final stanza—“trying,” “fight,” “die,” “rifle,” “wiping,” “while,” “pines,” “I’m,” “life”—create the deliberate, steady music of an American vernacular honed free of tricks or guile.

In “Youth,” the poet can’t keep a journalist’s distance from his subjects: the boys meld with him and his brother; the soldier could be his son. In “Breaker,” too, boundaries between subject and object won’t stay put. On the beach, refusing to take his hand, his partner’s daughter Hannah runs “like a foal does, all instinct and anxious need” as a seal slips down the face of a wave. But time shifts—this is a memory, Hannah’s grown up, and “other lives pour over her” like breakers—and so does point of view, as Sleigh becomes the seal. “I pop up above the waves, curious and wary of what the humans are doing,” Sleigh writes, his layered, intimate perceptions gliding from a particular this is me to the shared perspective of this is us.

Sleigh’s poems develop in a variety of forms. “Breaker” is a prose poem; the sonnet sequence “Stethoscope” includes one addressed by a lab dog to his leash (its final, elegiac litany—“August, Fast One./Pretty Little Lady, Joy, Beauty, Milord, Clown”—is reminiscent of Donald Hall’s “Names of Horses”). Sleigh’s sequence on Covid, “Little Testament,” has a little bit of everything: a sonnet, tercets, lines fractured by extra spacing or bitten off short. If love and war are narratives, plagues aren’t; Sleigh uses form to express the confusion of an incomprehensible story.

So how does one live with the knowledge of death without going crazy? The narrator in “The King’s Touch,” while undergoing an MRI for a brain tumor, substitutes science for royalty, now that we no longer believe in monarchs or the God that anoints them. Still, its secular power can’t help colliding with mystery. In the poem’s companion piece, “The King’s Evil,” Sleigh writes, “Oh King, I pray, don’t let me die today…let me feel Your sanctified Touch…that God, like a hand slipping inside a plastic surgical glove, is using….” We live not in spite of but because of inconsistencies, Sleigh suggests; in the book’s final poem, the “age of wonder” may be over but “we can still live, can’t we, inside its fading, as if it were the future/that year by year we age backward toward?”

Generous, meticulous, haunted and grounded, The King’s Touch handles contemporary life with alertness and compassion for a world in which “A Man Plays Debussy for a Blind, Eighty-Four-Year-Old Female Elephant” while friends kill themselves and voices urge, “You’re better off dead, you useless piece of shit.” The piano player “shuts his eyes and leans his forehead against hers,” Sleigh imagines; “it’s like each one’s/listening to what the other one’s thinking.” Sleigh’s business, like Dickinson’s, is circumference; though he can’t erase the voices that drive individuals and nations mad, they can be subsumed in music. Reading The King’s Touch is an extraordinary pleasure not to be missed.

Joyce Peseroff's fifth book of poems, Know Thyself, was designated a "must read" by the 2016 Massachusetts Book Award. Recent poems and reviews appear or are forthcoming in On the Seawall, Plume, Plume Anthology, and The Massachusetts Review. She directed UMass Boston's MFA Program in its first four years, and currently blogs on writing and literature at joycepeseroff.com