Unexpected Magnitudes: On David Rivard’s “Some of You Will Know”

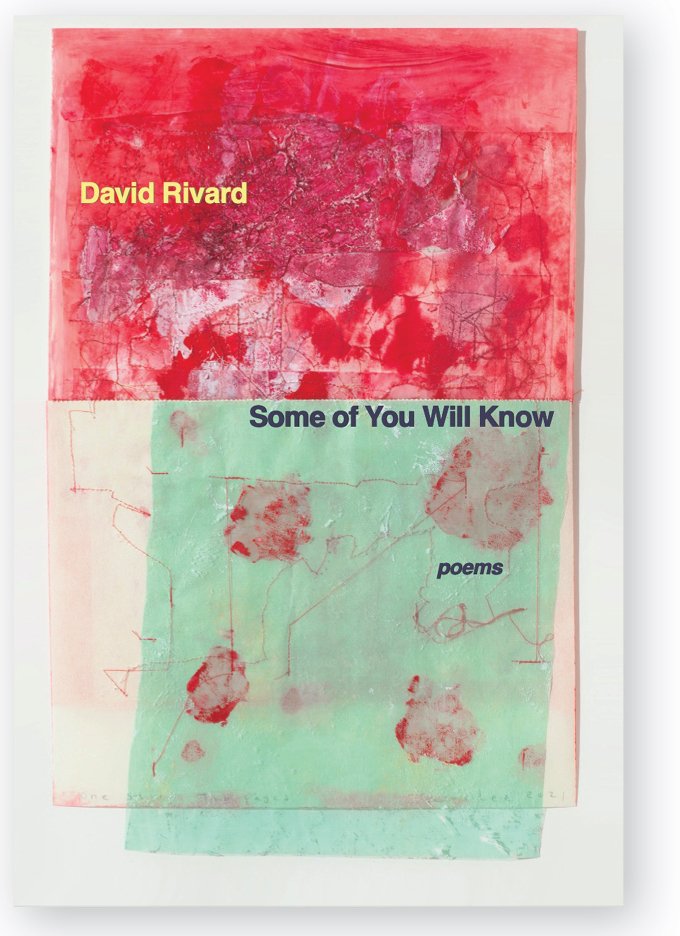

David Rivard’s poems have always found a way to outfox the dogmas grafted to the rootstock of whatever passes in American culture for The New. In book after book, and with great linguistic ingenuity, he’s explored the rift — now more of a chasm — that’s opened up between our contemporary consciousness that spiders out across the internet and social media and the desire to maintain a vital connection to a deep literary and artistic past. But for all his decades-long devotion to taking The Culture’s temperature — its flushed, not to say feverish social upheavals and ever-imminent crises — there’s something like a mathematical constant that pervades his work. Personal anguish colliding with wide-spread public consternation is the cultural and psychological terrain that he inhabits. Now that he’s on the brink of old age and looking up at what Philip Larkin once called “extinction’s alp,” the ground is obviously steeper than when he first set out thirty-six years ago with the publication of Torque (1987). Yet despite his awareness of the Doom Clock ticking down, he’s never cultivated a more youthful exuberance than in his most recent book Some of You Will Know (2022).

This vitality springs from his devotion to writing not with the eye but through the ear. His lines have an attractive improvisational quality, as if they were spontaneously uttered as opposed to written down. And yet there is nothing chatty or casual or half-baked in his poems. The acoustic freshness he achieves is due to the way the lines skillfully and painstakingly enact every slightest shift, every nuance of changing mood in voice and consciousness, as they occur along the line. More than most poets, Rivard understands the formal consequences of words as a temporal medium, one word paying out after another in order to create certain emotive/intellectual complexes (as Pound once said of Imagism) that then give way to the next and the next. There’s a congruence between his thinking and feeling and his feel for the line. In that sense, he’s a consummately formal writer, deeply wired into the history of the big booming English line as it comes through Spenser, Sidney, Shakespeare, Pope, Wordsworth, and Keats; but he also knows and cares about the atomization of that line into what Frost called “significant vocal tones,” tones that carry in solution a whole community’s way of speech, seeping like underground spring water into his own. His working class, New Bedford urban roots — what you might call his “linguistic ethnicity” — share rich common ground with the intimate, hedged, psychological uncertainties of Williams, Oppen, and Creeley. He knows Bishop backwards and forwards but would seem to prefer Niedecker’s nervously shifting lines often resolving in lush full rhymes, but rhymes that are metrically off-kilter enough so that they don’t insist on themselves. He’s also ventured abroad, taking in Miłosz’s skeptical grandeur, as well as Szymborska’s sly fox embrace of irony and contradiction. Lastly, he’s in love with Rimbaud — but not the Rimbaud of Louise Varese’s able yet decorous translations, nor Paul Schmitt’s channeling of Rimbaud in a straightforward English idiom that, for all Schmitt’s heartfelt conviction that “an equation between line and sentence” is the translator’s key, comes off as a little low-watt. Instead, Rivard’s Rimbaud is the shrewd blaspheme-talking townie of Stephen Berg, or the unfussily elegant effortlessness of John Ashbery’s version of Illuminations. Which is to say that Rivard’s style isn’t so much a unified field of rhetorical moves as it is a total mobilization of a poetic voice that extends as deep into his own psyche as it does into the digitally unstable, rushing-toward-doom, click-bait obsessed present.

In the inward mode, he writes about the dissolution of a marriage, but with an obliquity that isn’t much interested in telling a narratively coherent story. Instead, he gives us the emotions of autobiographical revelation without overdoing the literal details. There is one plangent and deeply felt exception: the aura of loss that surrounds this book is grounded in a prose poem entitled “What Really Happened Yesterday, Yesterday Will Never Know.” This poem is as autobiographically direct as Rivard gets:

Outside the cabin, a glove dropped years ago. The empty black calfskin skitters across the road, blown by a gust & the tarmac seems to ripple & swell—like water pushed by wind on the river.

The man who stays in this cabin, his long marriage is over. Who is he now having been concealed after all by all that he seemed? A home…the marble coolness of the bathroom tiles on the soles of his feet in summer…trees on the street outside, their leaves rustling in the wind a signal to a barking dog—a city life, one house hidden behind another.

Even this relatively straightforward account — a lost glove, the wind rippling the river, a cabin retreated to from a home no longer home, the memory of cool marble bathroom tiles, the barking of a dog aroused by leaves rustling — eventually these details of a past life give way to the enigma of a house hidden behind another behind another. Which leads you to rethink the apparent casualness of the recollection. Now the lost glove seems fraught with bad juju, the wind takes on ominous overtones of Fate subtly and inexorably working against the man, the tiles and trees and barking dog become devastating emblems of the exile’s wounded and wounding memory.

In less skilled hands, the temptation to ratchet the drama into melodrama or goose the poem up with lyric lament would be well-nigh irresistible. But Rivard always keeps his autobiographical self at a healthy arms-length from his analytical self. Rivard “martyrs himself to the human heart,” as Keats once said of Wordsworth, but not as an excuse for Wordsworthian expostulation. He’s more interested in examining and arraigning his own behavior than in using the poem as a kind of theater of self-forgiveness or self-justification. Yet this distanced way of treating the self, rueful and sorrowing as it is, does produce a kind of catharsis, if only the catharsis of finally seeing yourself straight on, warts and all. But first you have to get outside of yourself, establish a perimeter, a sort of psychological caution tape marking off a crime that Rivard, as a sort of detective of the soul, coolly walks around trying to pick up clues, faded footprints, the snapped twigs and unnoticed signs of coming disaster that were so obliviously missed. A disaster made worse by the fact that the man brought it on himself.

What at first may seem indirect, even evasive, in Rivard’s poems, is actually a form of emotional integrity, an unsparing honesty trying to understand how you could have fucked up this badly, this unthinkingly, and with such irrevocable consequences. This is as much a matter of taking stock of what Seamus Heaney (quoting the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam) once called our “responsible tristia” — the harm we know we’ve done to others — as it is an act of tact toward the other people in the poem, a wife and daughter. But acknowledging the hurt he’s caused doesn’t absolve him. Even worse, the poet wants desperately not to compound the hurt by writing too nakedly about it, even as he knows that the mere act of writing about it at all will inevitably be offensive. This isn’t a double-bind that the poet tries to solve or brush away. After having a dream of locking the door to his old house for the final time, the poet ends the poem like this:

And this man whose marriage is over now, where did he go then? Maybe he’d had to walk into something he wanted so badly to be the edge of a forest that it became the edge of a forest. Maybe he thought, “I won’t be away for long.” Oh, but he will be. He was.

The sorrowing sense of a soul in emotional limbo or worse, hopelessly lost or in permanent exile, doesn’t obviate in the least that soul’s culpability. But you might also say — and I want to say this as tentatively as possible — that the poet’s self-accusation, his frank avowal of an ethical ideal of kindness and care that the poet has forever fallen from, could also be seen as a form of poetic generosity, even if it does nothing to assuage the real-life damage.

Is hurt — not only the hurt he’s inflicted on his wife and daughter, but also on himself — the whole story? Yes, betrayal, disappointed hopes, the hard give and take of a shared life worn to rags hover like spectral presences over the self-confrontations/accusations in many of these poems. But there’s a broader perspective to take into account, one that can’t wipe away the tears, but affirms that a broken life can also be a life worth living. As the book progresses, the poems come to explore what you might call a purgatorial understanding of the literal circumstances. The he said/she said, the faults-on-both-sides tact (and tactic), the this-happened-then-that-happened of the more conventionally direct speaker of “What Really Happened Yesterday, Yesterday Will Never Know” begin to transform into a kind of private confessional. Only there is no priest to hear you out and absolve you, there’s just the naked self subjected to its own quietly devastating, but ultimately regenerative, third degree:

“You aren’t the first to feel these things—

or are you? would you like to have been?

you whose loneliness became you

if you thought yourself the first

would it change you (I bet that

you would like to be changed) humbled

by being chosen reborn

would you even know you’d been

reborn (I think you would) after all

you’d woken helmetless last night

again and again before the sun returned

the sun as usual bristling a little then

don’t deny the gift of happiness don’t

think it’s meaningless even if it fades…

Lest this kind of self-inquisition seem a little too automatic, even to the point of becoming a rhetorical tic, the last two lines offer up at least the hope of a reprieve, even if it’s transitory, prone to vanish just as you try to embrace it. This analytically cool way of proceeding may puzzle some readers who want their poetry bloody and bristling with “feelings.” I often think of Gregory Corso’s brilliantly funny take down in “Marriage” of such Romantic expectations: “Feel! It is beautiful to feel!” Integrity of feeling, not feelings per se, is the unstinting abundance that these poems have to offer. In that way, they are original and ungainsayable.

In comparison, most poets feel either flashily verbal or ploddingly literal — as if weirdness for its own sake wasn’t as potentially inert as an idiom that barely rises to New York Times-ese. Rivard’s tonal fidelity to complex emotion complexly expressed proves him to be virtuosic in discovering a syntax that perfectly embodies the fluctuations and shifts of conscience. As if that weren’t enough (and it assuredly isn’t for this poet!) he also displays a genius for phrasemaking that feels emotionally and intellectually grounded, even as it freelances out along the linguistic edge. This doubleness of focus drills down into the past and seems as much characteristic of Father Hopkins as it does of the self-proclaimed avant-garde. Hopkins’ “Carrion comfort” would feel right at home among such Rivard phrases as “February’s basket-case sunset” or “skyline-jamming windfarm.” All of these perceptions are more than just descriptive, and more than just description “imbued with emotion,” as the old critical dispensation used to say.

Here is a typical example of his eye at work, but with his “I” focused outward. When Rimbaud said, “Je est un autre,” (I is an other, as opposed to I am an other), he expressed the displaced, ironically distanced way that Rivard aligns his “I” with his perceiving eye’s oblique way of seeing:

A starling

wades in a wide bowl in the garden,

the water cooled by the bowl’s thick stone

dark & clean & earthly

like water that dried mushrooms have soaked in,

a calming, almost

personal transparency that coats the bird’s feathers

and that she takes with her to a branch,

where she shakes her short, square-tipped tail

and flies off inside a spray

of iridescent droplets in the noonish air,

‘each drop a petty tricolor’

in the solstice heat building out of June,

that moment of July

when a video of the long line

of refrigerated freight cars

stacked with black body bags

in an insurgent-controlled Ukrainian

train depot surfaces

in the newsfeed all of a sudden, on that sunny, bacon-fat

morning two days after the otherwise intangible day

an airliner full of human bodies

disintegrates at altitude

in the sky

over cornfields and sunflowers

in the Donetsk Oblast…

Much could be said about the movement from the first to the second stanza — the juxtaposition of the bird immersed in nature and the body bags subsumed not only by the constant scrolling of the newsfeed, but by the simultaneity of “the sunny, bacon-fat/morning” and the unruffled, unnoticing cornfields and sunflowers. But that view would miss what is even more remarkable: how the casualness of tone in the pleasure of the morning havocs with what you might call the poet’s moral sense — a grimly, even jauntily ironic casualness that can barely keep itself from clowning around in the face of body parts gathered up and put in individual body bags. On the one hand, the poet is morally strung up and strung out; on the other, his eye acknowledges that the bird is doing what it always does, bathing to cool off and clean up, then winging away into the morning.

In the meantime, the poet’s use of “bacon-fat” is horribly suggestive of corpses bloating in the heat, as well as the ripeness of high summer. The two perceptions playing off each other make both that much more arresting. Not in the least disturbed by the metal bird fallen from the sky, the starling is insulated in its “personal transparency” from the investigators depicted in this little imagistic miracle of depersonalized humanity:

The investigators wear haz-mat suits

of white Tyvek & goggles

dark and shiny as the pupils of salmon

buried to their chins in crushed ice.

In its compression and deadpan understatement, these four lines beat whole books of prefab outrage in which you can see the attitudes coming from around the corner, making no discovery, afraid of self-implication, unable to find a personal stake in the material beyond its sorrowful topicality. By contrast, no poet this century or last has written anything more comprehensive of the ordinary horror of necessary, common-sense bureaucratic protocols in encountering and disposing of atrocity.

This kind of ironized yet corrosive knowledge of the desolating news cycle amounts to much more than the old Latin tag, Homo homini lupus (Man is a wolf to man). There’s a sacramental quality to the role perception plays throughout Rivard’s work. No matter how bleak and brutal the material, the depiction of the starling taking a bath in the first stanza is rendered in an idiom so lush in its Keatsian assonantal acoustic that you feel the poet pushing back, trying to find a balm, a solace—not something as affirmative as “life is worth it, no matter the pain,” but something more nuanced, more like “yes, pain is as much a universal constant as gravity, but why shouldn’t the starling’s primal vitality exert an equal and opposite, that is to say, life-affirming reaction?”

…she shakes her square, short-tipped tail

and flies off inside a spray

of iridescent droplets in the noonish air,

‘each drop a petty tricolor’

This has something of Hopkins’s transcendent wonder in “The Windhover” in which the heart “in hiding/Stirred for a bird,—the achieve of, the mastery of the thing!” Rivard is more measured, of course. Perhaps he’d hedge his bets by saying the balance between the atrocious and the evocation of a bird flying off “inside a spray/of iridescent droplets/ ‘each drop a petty tricolor’ ” (Wallace Stevens) can be maintained only inside the imaginative moment of the poem. When you stop reading, the mutilated flesh is still mutilated, the starling is just a bird indifferent to the fate of mortals falling from the sky. That an art such as Rivard’s can quicken us, can push back against what Stevens called “the pressure of reality,” is no small thing. Nor is it a small thing to be the kind of poet who routinely works such miraculous, alchemical transformations of broken, bleeding flesh into the transubstantial gold of the primal Word…at least for as long as it takes to read a Rivard poem.

There are very few poets of any era who have this head-clearing, salutary effect on our doom-ridden awareness that the wings are beginning to wrench loose from the plane. But since none of us can sustain that kind of apocalyptic vision for long, I want to turn to a final instance of his various and multi-hued sensibility. In “Eyes Closed, Rye Beach,” he writes:

…Amy has walked into the water

in her expensive bra,

and afterwards her cut-offs

will be bettered

because the sea has made them softer

with its saltiness

and all that rubbing I can

see with my eyes closed because

I can hear the waves

breaking.

Any one of us can see

with our ears if we want—

but no one should try too hard—

ego isn’t in it—tho a hunger for mercies might be:

my marriage is over

now—my father has been dead

five years—Tony has died,

without a word—the hooded child

lags farther & farther behind, startled,

out-of-touch—and I am not the one

who knows how to pray—

all those bits & pieces

of a story I brought with me to Amy.

This is far from the atrocities of the Donetsk Oblast and the haunted house of lost domesticity. It’s still focused on loss, though, a catalog of losses in fact: a broken marriage, a dead father, an estranged dead friend, the poet’s own childhood self lagging “farther and farther behind.” Everything familiar has been dashed on the rocks of circumstance, and now all that seems to be left is the salt-soaked flotsam and jetsam that has washed up after the shipwreck. But out of this sea of losses, and even though he has his eyes closed, the poet can feel the intimations of a mysterious reckoning, what Stevens called “…a light, a power, the miraculous influence” in which “…a look or a touch reveals its unexpected magnitudes.” In the presence of love, of Amy wading out into the sea beyond the poet on shore, suddenly the “bits and pieces” no longer seem so broken, so pointless. For the sea isn’t only brute force, it’s also Eros, and the way Eros remakes the world; it’s the way sun and salt and the erotic combine to soften and even soothe; a quiet proffering, you might say, of the mercies the poet hungers for as he sums up the disasters of his life. But in the presence of the beloved what seems hopelessly fragmented begins, miraculously, to reassemble, to offer a kind of secular, sensual benediction:

When Amy comes back

from her swim it’s almost the ocean

that presses its wet palm against my forehead—

cold, reliable, grinding, restorative—

but in the gear whine of two motorcycles racing

a half-mile away

I see us passing once more

into the safekeeping of Shaker bees

as we walked the hillside yesterday

below those dormitories no one goes to any longer

for sleep. The pollen of thousands

of pine trees powdered across

the greenest leaves there, the yellow-white stipple

of dots I’d wiped my thumb over

while passing. “Snowflake Appaloosa

is the loveliest phrase,” the guide had said

as she stood in the doorway

to the apiary like a password. I thought that too

of course. The yellow streak of my thumb

across Amy’s palm. We’d just left

the stables. I thought that

yesterday. Still do.

I needn’t belabor the casual mastery of Rivard’s evocation of the racing motorcycles, the poet’s forehead pressed to Amy’s palm cold and bracing and restorative as the ocean itself; or the way the Shaker bees are half-humorously turned into momentary guardians as the poet and the beloved proceed to where the stable guide will seem to utter the password and the door will swing back — to reveal what? Well, nothing that wasn’t already there in the real world to be seen and pondered and be inspired by: the spectacle of the pollen falling as if it were a blessing, but also just ordinary pollen; how the guide’s affection for the term “Snowflake Appaloosa” reveals language’s power to usher us forward into new states of consciousness, but is also just a term for a horse with white spots; how the “yellow streak of my thumb/across Amy’s palm” reveals the “unexpected magnitudes” that touch can manifest, even as a small, private gesture of affection.

Yet there’s no denying that something in the poet’s psyche has shifted. Without quite knowing how or why, and certainly not because he willed it, the poet is beginning to sense a new world coming into being. It’s as if the ocean pressing “its wet palm against my forehead—/cold, reliable, grinding, restorative—” has created not only a moment of reprieve, but of revelation. Suddenly, “in the gear whine of two motorcycles racing,” the poet is granted passage into “the safekeeping of Shaker bees.” In the hands of a lesser poet, the winding out of the gears to express the poet’s revved up sense of possibility might seem too clever by half, or merely goofy. But Rivard’s matter of fact treatment of the “gear whine” undercuts the potential sentimentality always lurking on the fringe of any epiphanic moment.

Rivard has a genius for knowing when emotion is in danger of turning into emoting. Plus, there’s something wonderfully inclusive and frank in acknowledging that a Kawasaki Ninja H2 can be as much a vehicle to the transcendent as Dante’s “music of the stars.” Equally impressive is how the ocean’s salty abrasiveness seems of a piece with the gear whine, such that waves breaking and fourstrokes revving are both apt indicators of the state of the soul.

But what I admire most about Rivard’s work is how the revelation of love and continuance at the end of the poem in no way negates the losses still weighing the poet down. He knows that it’s a real ocean after all, full of sharks and rip tides, just as the protecting Shaker bees still have stingers, and motorcycles racing can end up in twisted wreckage and mangled bodies. Throughout his career, this recognition that disaster and renewal are continuums, not antinomies, has been fundamental to Rivard’s work. You can sense this brilliantly embodied throughout this poem in the swerving reversals of the syntax, the interplay among the long and short sentences propelling the poem to its quietly hopeful conclusion. It’s as if a sacramental counterforce, an opposite and equal reaction, has been set in motion by the pine trees’ sudden release of pollen: “the yellow-white stipple/of dots I’d wiped my thumb over” seems to herald an unasked for, unprayed for emotional grace. And as the magnitude of this grace founded in touch lifts and lightens, it also suggests the hope of a shared continuous life, of a world still unfolding, of a renewed sense of potential underwritten and verified by the power of “the loveliest phrase.”

Tom Sleigh is the author of eleven books of poetry including winner of the 2023 Paterson Poetry Prize The King’s Touch (Graywolf Press, 2022), House of Fact, House of Ruin (Graywolf Press, 2018), Station Zed (Graywolf Press, 2015), and Army Cats (Graywolf Press, 2011). His most recent book of essays, The Land Between Two Rivers: Writing In an Age of Refugees (Graywolf Press, 2018) recounts his time as a journalist in the Middle East and Africa. He has been a Guggenheim Fellow, NEA grant recipient, and winner of numerous awards including the Kingsley Tufts Award, Shelley Memorial Award from the Poetry Society of America, John Updike Award and Academy Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. His poems appear in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Threepenny Review, Poetry, The Southern Review, Harvard Review, Raritan, The Common and many other magazines. He is a Distinguished Professor in the MFA Program at Hunter College and lives in Brooklyn, NY.