Alexander Dreier: In the Wild

How many worlds do we live in? How many worlds live in us? How many portals to how many realms are always half-open within us or in the world we walk through so thoughtlessly? Maurice Merleau-Ponty famously said: “The things of the world are not simply neutral objects before our contemplation; each symbolizes or recalls a certain mode of conduct…each speaks to our body and to our life.” Things “haunt our dreams,” they are “clothed in human characteristics,” and “they dwell in us as emblems of behavior we either love or hate.” ¹

The daring anthropologist, Eduardo Kohn, spent four years in Ecuador’s upper Amazon living with and learning from the Runa people. His book, How Forests Think, explores the profoundly inter-subjective/inter-species ecology of forest flora, fauna, and forest dwellers. The Runa survive amid violent storms and floods, endure the depredations of bandits, government officials, rubber tappers, survive by hunting birds, tapirs, fish, and finding root vegetables. To endure, they rely not so much on inferences derived from scientific uniformities as on intuition, ancestral lore, visions; a kind of inwardness that gives them flexible and constant links into the living world.

At one point, Kohn speaks of a dream he had and discussed with some of his Runa informants. “I’ve come to wonder how much of my dream was ever really my own: for a moment, perhaps, my thinking became one with what the forest thinks. Perhaps… There is indeed something about such dreams which “think in men unbeknownst to them,” (C.S. Pierce). Dreaming may be then a sort of thought run wild — a human form of thinking that goes well beyond the human… Dreaming is a sort of “pensée sauvage” (wild thought): a human form of thinking unfettered from its own intentions and therefore susceptible to the play of forms in which it has become immersed… which in my case... is one that gets caught up and amplified in the multispecies, memory-laden wilderness of an Amazon forest.” ²

Kohn describes specific ways by which our inner life organically interpenetrates and is interpenetrated by our outer environment. This is a kind of experiencing common throughout our history and world. Meaning, in this context, is not based on convention, fixed references, social purpose, or intent, but on more extensive, free-flowing associations, and intuitive, multi-dimensional linkages. There are societies that recognize the validity of such kinds of awareness, but for those raised in the West, such an experience, particularly when it is unsought, is deeply disturbing. It is rare that someone, finding her or himself prone to such kinds of cognition, would seek to find its truths.

Again Kohn: “This kind of exploratory freedom is I think what Claude Lévi-Strauss was getting at when he wrote of wild thought as ‘mind in its untamed state as distinct from mind cultivated or domesticated for the purpose of yielding a return.’” ³

Alexander Dreier was born in 1949 and died 70 years later. He was very much a product of New England. His father was a career diplomat and his mother a gifted painter. He was a profoundly ethical and creative man, fortunate in that his circumstances allowed, even encouraged him to pursue interests and commitments infrequently followed by others. He was a farmer, therapist, poet, and comic, dedicated to implementing the spiritual and ecological thinking of Rudolf Steiner. In 1963, he was diagnosed with Lewy Body disease, a disorder which produces disorientation, hallucinations, and finally extreme dementia. This is what caused his death.

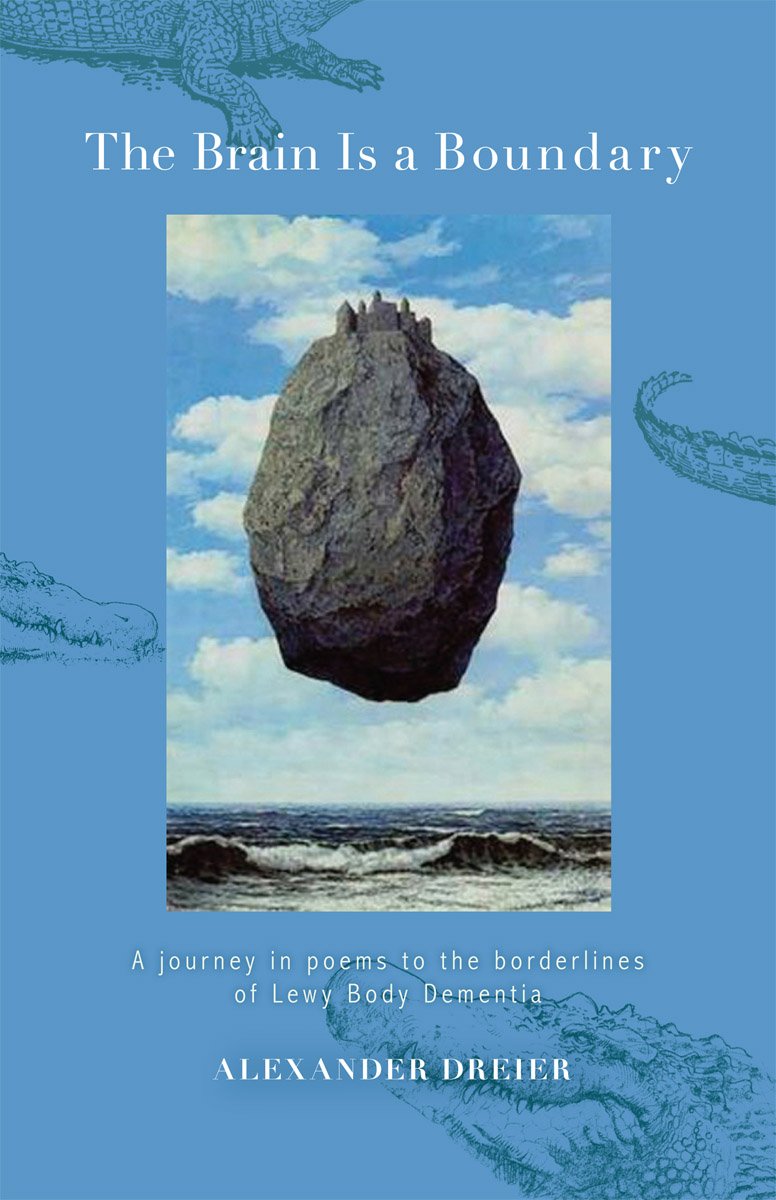

Alexander did not merely accept his diagnosis, he embraced the disease and considered the strange phenomena which he then experienced as a sequence of adventures and revelations. He wrote an account of this journey in poetry and prose, in his extraordinary book, The Brain is a Boundary. The prose portion of the book begins:

“In the summer of 2014, on an early morning walk near our cabin on an island off the coast of Maine, where I was enjoying a solitary retreat, I came across a group of indigenous looking children dressed in clothes made of leaves. Ignoring my greeting, they followed me right into the house where their apparent ringleader, a three-foot tall man with dreadlocks, who appeared to have a hose coming out of his head, was engaging a group of adults in some kind of ritual. Fascinated as I was by their ceremonies which involved magical screens and spinning trees, I eventually called the local sheriff to have them removed from the property. It was then after 10 pm. They had long overstayed their welcome and refused to respond to my most basic questions: “Who are you? Why are you here? What are you doing?”

The next day, my wife, Olivia, and my brother-in-law arrived and finally convinced me that this strange cast of characters had all been a very long ‘waking dream.’” ⁴

This was all part of Alexander’s clear-eyed and direct exploration of a world in which waking life and dreams are not segregated but interpenetrate unpredictably and continuously. He did not wish to banish or eliminate these often inconvenient if slightly numinous phenomena, and he tried to negotiate a way of living in an unstable existence which might, without warning, veer between the radiant and seductive and the outright ominous. This involved seeing the world as more porous, more pregnant with images and meanings, and it involved regarding himself in a different way.

As to the former, he said: “In my experience, things that are ordinary often become extraordinary. This then presents me with an invitation to encounter that extraordinariness in whatever way I am able or willing… The medicines I am taking keep this often surprising imagery at a level where it mostly does not alarm me but rather, in all kinds of interesting ways, leads me to question what I am seeing, (though) I do have difficulty working with the normal dimensions of time.”

Alexander’s friend, Arthur Zajonc, who shared exploring dementia though he had Parkinson’s, put it this way: “For people like Alexander and me, the solid grounding offered by outer experience may be weakened so that the mind is less tightly tethered to the sense world.” ⁶

As to the latter, his experience of himself, he said in a poem that he found that:

“only the sky is his one true brain.” ⁷

And so, one of his last poems:

THE MESSENGER

Who but the last cloud

Knows what this isthmus is,

Not narrow mined but ground,

Down where arrival is departure,

Where contrails of sweat-soaked

Expectations slip into streaming

Blue lightness? Who do eyes see

Without the cartload of luggage we

Gathered up before words,

When I first noticed you at the

Fiery open threshold, wearing

The dusty old hat of the universe?

You were arresting, radiant palms,

Facing the midheaven, where

The cusp was in big beginning

Of the whole high domicile,

Meridians alive for all to feel.

Yes you, transparent crescent

Of becoming, as the gateway

To the liminal horizon, as

Messenger of the not yet born. ⁸

And then, the last poem in his book begins:

“Please accept this prayer.”

And it ends:

“Please, say this with me now.” ⁹

When his illness was quite far advanced, Drier’s son, who had been working as an aid worker in Columbia, took him to meet some of the healers there. He told a shaman about his illness and the hallucinations it brought. “Do not be afraid,” the man told him, “This is the spiritual dimension allowing you to see her aliveness,” ¹⁰ This advice gave Dreier great confidence and allowed him to engage the phenomena emerging around him in a remarkably open way.

It might seem that it is willfully naïve or cruelly romantic to look at distortions and hallucinations prompted by a terrible disease as affording kinds of insights and experiences of real profundity. But looking directly at his experience, at what was being given him, without regard for cause or context, allowed Drier to explore and communicate with something deeper in the world. He had the courage and love to explore our wild mind.

Lévi-Strauss observed: “whether one deplores it or rejoices in it, zones are still known in which wild thought, like a wild species, is relatively protected. Such is the case of art, to which our civilization gives the status of a national park, with all the advantages and disadvantages attaching to such an artificial formula…” May all this searching which we call our arts open doorways through the walls and conventions that we think protect us. ¹¹

_______________________

1 Maurice Merleau-Ponty, “Exploring the World of Perception: Sensory Objects.” Tr. Zemka, The French Cultural Hour, French National Radio 10/23/1948, Institut National de l’Audiovisuel. Cited in , cited in Sue Zemka, Descent, Spirit, Heart, Senses. (Academia) p.22)

2 Eduardo Kohn, How Forests Think, U. Cal. Press, 2013 P.195

3 Eduardo Kohn, ibid. P.177

4 Alexander Dreier, The Brain Is a Boundary, Lindisfarne Books, 2016, p.93

5 Dreier, ibid. P. 103

6 Zajonc in Dreier, ibid. P. xvii

7 Dreier, ibid. P. 74

8 Dreier, ibid.. P. 88

9 Dreier, supra p.89

10 Dreier, supra, p.105

11 Claude Lévi-Strauss, Wild Thought, tr. Mehlman and Leavittt, Chicago UP, 2021, p.247

Douglas Penick’s work appeared in Tricycle, Descant, New England Review, Parabola, Chicago Quarterly, Publishers Weekly, Agni, Kyoto Journal, Berfrois, 3AM, The Utne Reader, and Consequences, among others. He has written texts for operas (Munich Biennale, Santa Fe Opera), and, on a grant from the Witter Bynner Foundation, three separate episodes from the Gesar of Ling epic. His novel, Following The North Star was published by Publerati. Wakefield Press published his and Charles Ré’s translation of Pascal Quignard’s A Terrace In Rome. His book of essays, The Age of Waiting, which engages the atmospheres of ecological collapse, will be published in 2020 by Arrowsmith Press.