Utopia Lost

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Clifton%27s_Cafeteria_2017.jpg

People go to Clifton’s Cafeteria to see the place that inspired Walt Disney to build Disneyland. They go to soak in the atmosphere that helped Ray Bradbury imagine life on other planets. Clifton’s is a trippy Los Angeles legend that served cafeteria food to everyone from Charles Bukowski to the mom from Lassie. I didn’t seek it out for the usual reasons; I turned up there because they let my grandpa sleep in the alley behind the kitchen during the Great Depression. When mass unemployment hit L.A., the city responded by cracking down on its growing unhoused population with vagrancy arrests. A safe spot to sleep was a godsend. Clifton’s Cafeteria gave out free meals to anyone who couldn’t afford them, and those meals helped millions of Angelenos live through the Depression, including my grandpa. Grandpa George died before I was born. I guess I wanted to feel closer to him, to understand something about who he was. Visiting the place where he slept under the stars — and dined with the stars, for free — seemed like a good place to start.

Clifford Clinton opened what became known as the Cafeteria of the Golden Rule in 1931. The slogan was “Pay What You Wish, Dine Free Unless Delighted.” The unconditional generosity of it — pay what you wish, not just pay what you can — is stunning in today’s world of prices driven by steep downtown rents. Skeptics predicted bankruptcy within a year. Fortunately for Grandpa George, the volume of customers, both paying and not, made the cafeteria a success. Clinton let his imagination run wild when he designed the second location, Clifton’s Brookdale. He took inspiration from the Santa Cruz forests he loved as a kid, wrapping hollowed-out redwood trunks around the support columns to create an indoor grove. He populated the cafeteria with woodland creatures: an animatronic racoon waving here, a taxidermied bear fishing there. A moose head watched over the dining room with antlers spread like angel wings. The place attracted a mix of clientele that is hard to imagine eating together today: the penniless, Hollywood royalty, and everyone in between. Jack Kerouac described the scene in On the Road as, “a cafeteria downtown which was decorated to look like a grotto, with metal tits spurting everywhere and great impersonal stone buttockses belonging to deities and soapy Neptune.” Kerouac’s description, lurid as it is, undersells the pageantry of Clifton’s. There was the 20-foot waterfall, and then there was the limeade fountain where anyone could dip a cup for a free drink. There was the cave with an automated “mine” dishing out free sherbet. According to Los Angeles Magazine, Clifton’s even offered free therapy, “Personal Problem Guidance,” which encouraged guests to talk out their issues with restaurant workers, including Clinton himself. No one was a “customer” or an “employee.” At Clifton’s, there were “guests” and “associates.” And the egalitarian language wasn’t just for show — all associates had free healthcare and membership in a voting board that governed the company.

My parents and I made a pilgrimage to Clifton’s the summer before the Covid pandemic. We wanted to see the alley where Grandpa George slept. Clifton’s was a bright spot in his formative years, which were mostly something out of a Dickens novel. His parents split up when he was a toddler and his mom decided to keep one son and put the other up for adoption. He was the one she gave up. At first, he got lucky: a Seventh-Day Adventist woman took him in and raised him with love. However, when he was in middle school, his adoptive mother died in the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918, leaving him effectively an orphan. Her sister took over from there, resentful of having another mouth to feed. Grandpa George worked his way through college, and just when his life was getting on track — right on time — there was the Great Depression. He found a way to make it work, barely. He would alternate between one year of medical school, crashing on couches and sleeping behind Clifton’s, and one year working at a print shop or a bakery where he made macaroons, saving up for the next year of school. An old photograph shows him looking quite the hipster with a pencil mustache turned up at the ends, hair swept back in unruly waves, round glasses, and a polka dot bow tie. By the time he married my grandma he’d shaved the mustache, gelled his hair straight, lost the cool glasses, and swapped the loud bow tie for a plain one. Eventually, Grandpa George tracked down his father and brother. He wanted to understand where he came from. He met each of them only once and they were paranoid, afraid he was sniffing around for money or trying to get his name in the will. They wanted nothing to do with him. After all that rejection, it wouldn’t have been surprising if he’d become a total misanthrope. Something kept him going though, something made him keep helping people in his work as a doctor.

When I arrived in L.A., I checked the hours and noticed the name had changed from Clifton’s Cafeteria to Clifton’s Republic — very power-to-the-people, I thought. To get there, my parents and I cut through the nerve center of L.A.’s effort to bring people back downtown. The neighborhood around Grand Avenue is the target of a redevelopment effort that’s trying to undo the suburbanization that drained downtown L.A. in the 1950s. This summer, a Frank Gehry-designed mega-residential/retail/hotel development, The Grand LA, opened across from Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall, complete with five restaurants and bars from celebrity chef José Andrés. Next to Disney Hall is billionaire Eli Broad’s $140 million contemporary art museum, designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro. The firm had transformed an abandoned rail line into the bustling bower of the High Line, now one of the most popular attractions in New York, and Broad was hoping for a similar miracle in downtown L.A.

The designer neighborhood is growing on the site of a long-erased community. Half a century ago, the area was known as Bunker Hill, a working-class neighborhood and a haven for immigrants. Bunker Hill was designated “blighted” with crime and razed to the ground in the 1960s, eliminating nearly 7,700 bedrooms that housed low-income residents and scattering the people who found refuge there. The fancier apartment and office towers that replaced the old housing struggled to attract tenants, and some parcels remained undeveloped for decades. Clifton’s was a 15-minute walk from there. The closer we got to Clifton’s, the more shops offered to buy gold and provide loans, the more metal grates rolled down after dark. We passed a man in a sleeping bag in front of an empty storefront, and I thought of Grandpa George. Another day, I would walk further and find the sidewalks lined with tents and makeshift beds for blocks on end. I’d seen those streets on the news: the stories about dangerous heat waves, the lack of water and bathrooms. L.A. has been funding more initiatives to help its unhoused residents in recent years, but a long history of underinvestment left nearly 42,000 people without housing at the last count. It’s much too little, much too late.

My parents and I showed up at Clifton’s in our tourist shorts. We’d been walking all day, and we were expecting a cafeteria. What we found under that kitschy wood façade was a line of partygoers in miniskirts and high heels waiting behind a velvet rope and a bouncer guarding the door. It turned out that in 2015, a change of ownership had transformed Clifton’s into a nightclub, the kind that enforces its dress code. I thought we were out of luck (shorts were explicitly banned), but my mom, she’s persistent. She walked up to the bouncer in her beat-up sneakers and told him all about Grandpa George. We waited for a few minutes and the bouncer brought out a co-worker who was thrilled to hear about an old-school Clifton’s regular. He kindly ushered my dorky-looking family past the line of well-dressed Angelenos with no cover charge.

Our complimentary tour began in what is now the lobby of Clifton’s Republic. We walked through the legendary indoor redwoods multiplied on murals that create the illusion of a deep forest. We passed boulders sprouting green silk leaves. A small stone chapel still played a recording of a Patience Strong poem that urges the listener to “stand very still in the heart of a wood” and listen to the wind in the trees. “You will draw from the silence the things that you need / Hope and courage and strength for your task,” Strong promises. There was never really silence at Clifton’s. In the 1930s, the soundtrack came from singing waitresses. In this new incarnation, dance music pounded through the grove. The few tables remaining in what used to be the dining room were empty. The action was elsewhere.

We followed our guide, an energetic, fast-talking man with contagious enthusiasm, to the cafeteria. It was a well-preserved relic: chrome accents, Art Deco light fixtures, honeycomb tile floor, empty glass display cases, empty everything. Where was the rainbow of Jell-O salads and strawberry pies on little white plates? Where were the people? Our guide said the cafeteria was part of the original reopening, but the format didn’t translate. Management was working on a new vision, something more like an upscale food hall, he explained. He agreed to show us the alley, and we followed him out the back door.

The space behind the kitchen was nothing like I’d imagined. My dream-alley was long and gray, something out of a Depression-era black-and-white photo. That night, I was standing in a tall thin shaft between the cafeteria and the red brick building behind it. A metal fence guarded it, spike prongs at the top looped with barbed wire. A blade sign spelled “Clifton’s” in a vertical column across from a line of dumpsters. I tried to envision Grandpa George in that alley, to intuit the spot where he lay down to sleep. He slipped away. I’d conjured him from photos, animated him with gestures that fit our family stories, made him speak in a voice I invented. He was just as much a figment of my imagination as the alley had been. I hadn’t traveled all that way to leave without learning anything about Grandpa George, though. Did he ask Clifford Clinton for “Personal Problem Guidance”? Is that how he ended up in the alley? What if Clinton was the father figure he never had? Everyone who could answer my questions was dead.

I looked up between the rooflines and counted the stars. My childhood bedroom was tiny. My mom made it feel spacious by painting it blue and hanging homemade clouds from the ceiling. The places we sleep shape us, they imprint themselves on us forever. I tried to feel the contours of the alley around me. The walls were tight, but then there was the deep dark sky overhead. Under that sky, my grandpa had to learn to trust the night. He had to let every conscious thought slip away, surrender, and dream. Sharing his space all those decades later, I caught him again. The air was chilly — I had goosebumps on my bare legs — but not cold enough to feel hostile. That’s L.A. for you. Behind the magical redwood forest, anything seems possible. Clifton’s is the kind of place that gives you permission to reinvent yourself again and again, until you get it right. The tragic orphan becomes a hipster, the hipster becomes a doctor.

We couldn’t stand in the alley forever, so we followed our guide into the nightclub. A substantial renovation carved a three-story atrium into the core of the building, where a fabricated redwood tree stretched from floor to ceiling. Crystal chandeliers hung from branches reinforced to bear the weight of aerialists dancing on silks. Each floor of the nightclub had a themed bar. At the base of the gargantuan redwood was The Monarch, modeled after a woodsy lodge, complete with natural-history-museum-style dioramas and a burly buffalo. Then there was the Pacific Seas, a nautical-themed tiki bar honoring the gaudy renovation of the first Clifton’s location. The Gothic Bar was named for the nineteenth century church altar that anchored a bar top carved from a giant sequoia that had fallen in a storm. It was there that the Los Angeles Science Fiction League met in the ‘30s, and the bar maintains a booth where Ray Bradbury sat. That’s the spot where, rumor has it, he made the bet that prompted L. Ron Hubbard to found Scientology. The Brookdale Ballroom hosts swing dancers and live bands with big horn sections, and another cocktail lounge rings the high branches of the redwood. Exploring Clifton’s Republic was like walking onto the set of a Baz Luhrmann movie — no, several Baz Luhrmann movies. My parents and I were woefully out of place on our family ghost hunt.

By the time I married my husband, all of our grandparents were dead. That generation attended our wedding by way of the framed pictures we set up in the reception hall. The grandparents posed in formal clothes, some in hats and gloves, some smiling, some somber. It was the closest thing to getting their blessing. Behind photo glass, Grandpa George stood with my parents on their wedding day. He was a compact man with ramrod posture. By then he had a white stripe across his dark hair, which he combed neatly across his head. His eyes hid behind thick-lensed thick-framed glasses. A photo has a way of being standoffish. There must be something of Grandpa George in me, but I’m not sure what it is. Years later, when I returned to the picture to search for a resemblance, I noticed his hand, the way the ring and pinky fingers curled tighter than the index and middle fingers. A visual rhyme caught my eye: my dad’s hand held the exact same position. I stood in front of a mirror and let my arms hang to the sides, stood at a slight angle, the way the wedding photo was posed. My hand did the same thing. It felt like the universe was teasing me. Okay, so I inherited his hands. What else?

I had the same feeling in college when I saw my cousin Kimberly after many years apart. My dad and his brother each had one daughter. On paper, my cousin and I were pretty different: I was a bookworm and she was a rodeo queen. But we both showed up in red and white striped shirts and identical Nike Shox sneakers, the ones with pink springs. We laughed it off, but it was freaky. It was a lite version of those stories of twins separated at birth, like James Arthur Springer and James Edward Lewis, who both worked as sheriffs, smoked Salems, drank Miller Lite, bit their fingernails, married first wives named Linda and second wives named Betty, and named their sons James Alan and James Allan. There’s something maddening about these family symmetries that are suggestive without being informative. It’s like seeing the tip of an iceberg. It’s like looking down and discovering that my feet aren’t moving, I’m not walking toward the destination I chose, I’m floating backward down a river of DNA and all I can do is flail around and try to get a glimpse of where I’m headed.

My parents and I skirted the periphery of the nightclub like the wallflowers we were. It was there that we found a glass display case with a black and white photo of Clifton’s in its heyday. Riverine neon lights snaked around the ceiling, giving an edge to the faux-stone bluffs and hanging baskets of greenery. A postcard with a cartoon stone chapel advertised in all caps: “PAY WHAT YOU WISH, DINE FREE UNLESS DELIGHTED.” It turned out that the early doubters were wrong, it wasn’t the pay-what-you-wish policy that did the cafeteria in. Clifton’s grew to several locations and thrived for many years. In the years after World War II, rising crime rates took a toll on downtown L.A. businesses, and those who could afford it moved to the suburbs. The original cafeteria shut down in 1960. Clifford Clinton devoted more time to his charity, Meals for Millions, and the cafeteria chain closed locations until it was down to the Brookdale flagship. With financial pressure mounting, the Clinton family sold its last outpost in 2010 to real estate developer Andrew Meieran, who promised to honor the original spirit.

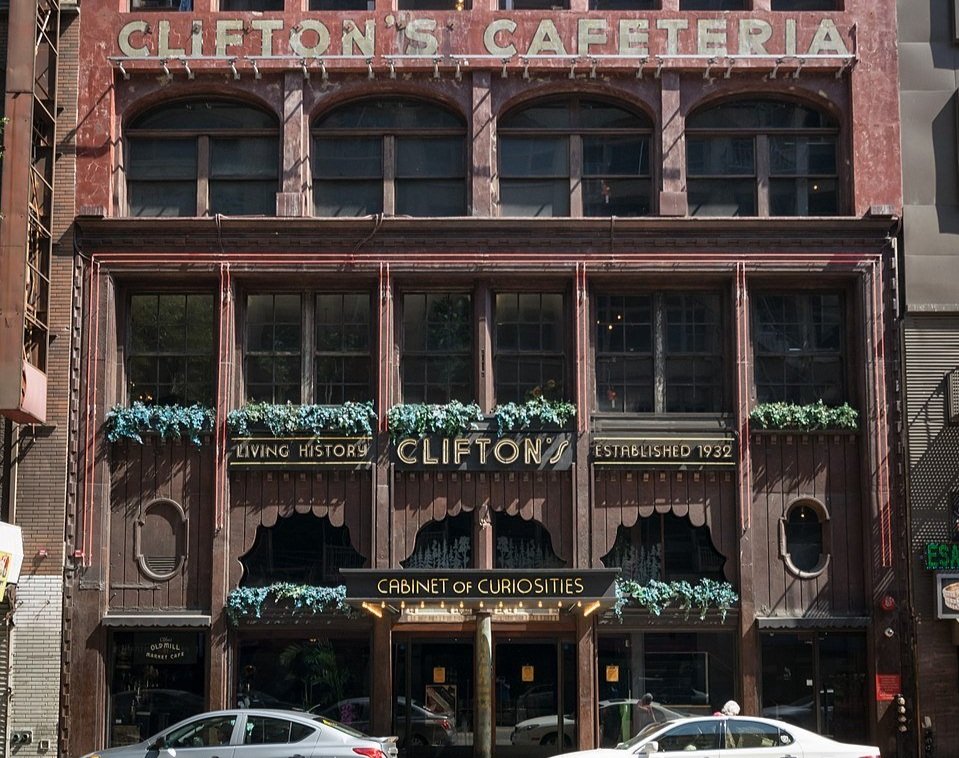

On the façade of the first Clifton’s, huge neon signs had broadcasted PAY WHAT YOU WISH and VISITORS WELCOME. Meieran’s Brookdale update brought back the neon with a new message: LIVING HISTORY and CABINET OF CURIOSITIES. That summer night, my parents and I walked out of the supersized wonderland, past the line of people waiting behind the velvet rope, and it occurred to me that Grandpa George never would have made it inside. Artifacts of the old Clifton’s were in cabinets, like the curiosities they are today. What is living history? The spectacle of Clifton’s lives on, but what about its spirit?

It’s complicated. Andrew Meieran is no stranger to taking on sacred spaces. Early in his career, he renovated California churches. When San Francisco’s earthquake-damaged Holy Cross Church was shut down and in danger of being torn down, he restored the original façade and turned it into lofts. He approached the Clifton’s redevelopment with care, reading Clifford Clinton’s diaries for inspiration while he sourced décor and oddities from flea markets and eBay. That approach led to unexpected yet apt features like the 4.5-billion-year-old meteorite dedicated to Ray Bradbury in the Gothic Bar. In interviews, Meieran’s love for the history of Clifton’s shines through. And these days, when you love something, you pay homage. You raise awareness. You redevelop it. You turn it into a sideshow. In my case: you write about it.

Times have changed since the first Clifton’s opened. Clifford Clinton invested an initial $2,000, or roughly $36,600 in today’s dollars, in a money-losing cafeteria to start his chain. Meieran took on what was supposed to be a $7 million renovation, but the price ballooned to $14 million according to the New York Times. Good, necessary safety regulations have raised the cost of construction since Clinton’s days, and then there’s the issue of chasing novelty. Clinton could bring some hollowed-out redwoods indoors and it was revolutionary. To make an impression today, Meieran hollowed out the whole building and constructed a three-story-tall crystal-bedecked redwood in the middle. In a post-Disney world, spectacle is an arms race. As far as the cafeteria’s charitable mission, the Clinton family acknowledged new challenges. “The face of the hungry person changed over those years,” Clifford’s grandson Robert Clinton told Los Angeles Magazine in 2015. “It was originally someone out of work, down on his luck. More recently that changed to people who were chronically homeless and mentally ill,” he said. Even so, the Clinton family kept the pay-what-you-wish policy until the day they closed the cafeteria. For Meieran, that status quo didn’t seem sustainable. “[T]he restrooms were the unofficial public rest-rooms for Broadway’s homeless,” he told Los Angeles Magazine. “We were spending tens of thousands of dollars on paper goods. But aside from that, there was the fact that you would come in and see people shooting up — it was a nightmare.” He argued that Clifton’s was giving back by creating jobs and attracting investment, all steps toward building an economically viable neighborhood. The result earned rave reviews from preservationists and politicians alike. The mayor of L.A. spoke at the ribbon-cutting, along with the councilman who spearheaded the “Bringing Back Broadway” plan to revitalize the surrounding neighborhood. The main target of criticism has been the closure of the cafeteria, which was so much more than an aesthetic. Promises of reopening surface here and there on social media, but it hasn’t materialized yet. The whole operation was closed for nearly two years during the pandemic — and that gets at the limitations that a cafeteria, a nightclub, or any business faces in trying to solve systemic problems. Businesses aren’t set up to provide services in a crisis, to be sustainable, to be accountable. That’s what government is for, and Clifford Clinton knew it.

Clinton had a popular radio show and a newsletter to spread his ideas, and he used his platform to launch a campaign to recall corrupt L.A. mayor Frank Shaw. Going up against a mob-tied mayor was dangerous. Shaw’s cronies tried to discredit him by calling him a communist, and when that didn’t work, Clinton’s home was bombed (luckily, no one was hurt). One of Clinton’s collaborators miraculously survived being riddled with more than 150 shards of shrapnel from a car bomb planted by an LAPD captain. In the end, the intimidation tactics backfired. The mayoral recall succeeded, and a Clinton ally was brought in to fight corruption. He ran for mayor himself as an independent in 1945. In L.A., it wasn’t impossible to imagine Clinton would win. The city came close to electing an actual socialist mayor in 1911 (when the candidate lost, he founded a utopian community in the desert). How would Clinton’s ideals translate from a cafeteria to a city? Not enough people wanted to find out. The mayor he’d shepherded into power was popular, and Clinton came away with only 19% of the vote. I can’t help wondering what could have been. Clifton’s Cafeteria sounds like a slice of paradise to me and I’m not alone; the word “utopia” comes up a lot when people describe it.

Losing the mayoral race ended Clinton’s political ambitions, but his influence still spread beyond the cafeterias. One example is personal. When Grandpa George finished medical school and my Grandma Erville finished nursing school, they moved to Stearns, Kentucky, to care for coal miners. They went on to help found a hospital in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. That’s where my dad was born. A few years back, when my dad was working at a cancer treatment technology company, he got to chatting with a younger Nigerian American co-worker. It turned out that he was born in Grandpa George’s hospital too; it’s still thriving. When my grandparents returned to the States, he always made time in his medical practice for patients who couldn’t pay. I think Clifford Clinton would have liked what my grandpa did with his life.

Three years later, Clifton’s still haunts me. The place started out as Hollywood glamor with a built-in breadline; now it’s a lightning rod for debates about who benefits from a downtown revival. I can’t help thinking of Clifford Clinton’s vision of rich and poor Angelenos eating together in the same dining room. It’s an optimistic view of humanity, that if we see each other, we’ll want to help each other. All these years later, echoes of the old Clifton’s remain in its lobby, in its curiosity cabinets, in old-timers’ stories. Utopia is there, commemorated in a glass case. The only thing more Californian than that would be filming it and putting it onscreen. If you find yourself in L.A., stop in at Clifton’s and visit the booth where Ray Bradbury envisioned a vertiginous range of possible futures. I like to think we’re not doomed to repeat the present. The past is full of lost possibility. In looking backward, maybe we can find that elusive jolt of radical imagination to change course. Get to Clifton’s early enough and you can dodge the velvet rope and the cover charge, and head straight for the redwoods.

Lisa Allen is a Boston-based writer with a penchant for research wormholes. She is currently working on a book about her encounters with forgotten and under-appreciated women artists. Lisa's writing has appeared in publications such as Meridian, Anti-Heroin Chic, Response, Ghost City Review, Kestrel, and Ghost Parachute. She is a graduate of UMass Boston's MFA program in fiction.