Back to School

Last August, the nurse made two announcements during back-to-school meetings: she’d put more band-aids in our first-aid kits, and the optional CPR training would start at 4 PM. This year, her announcements last three days.

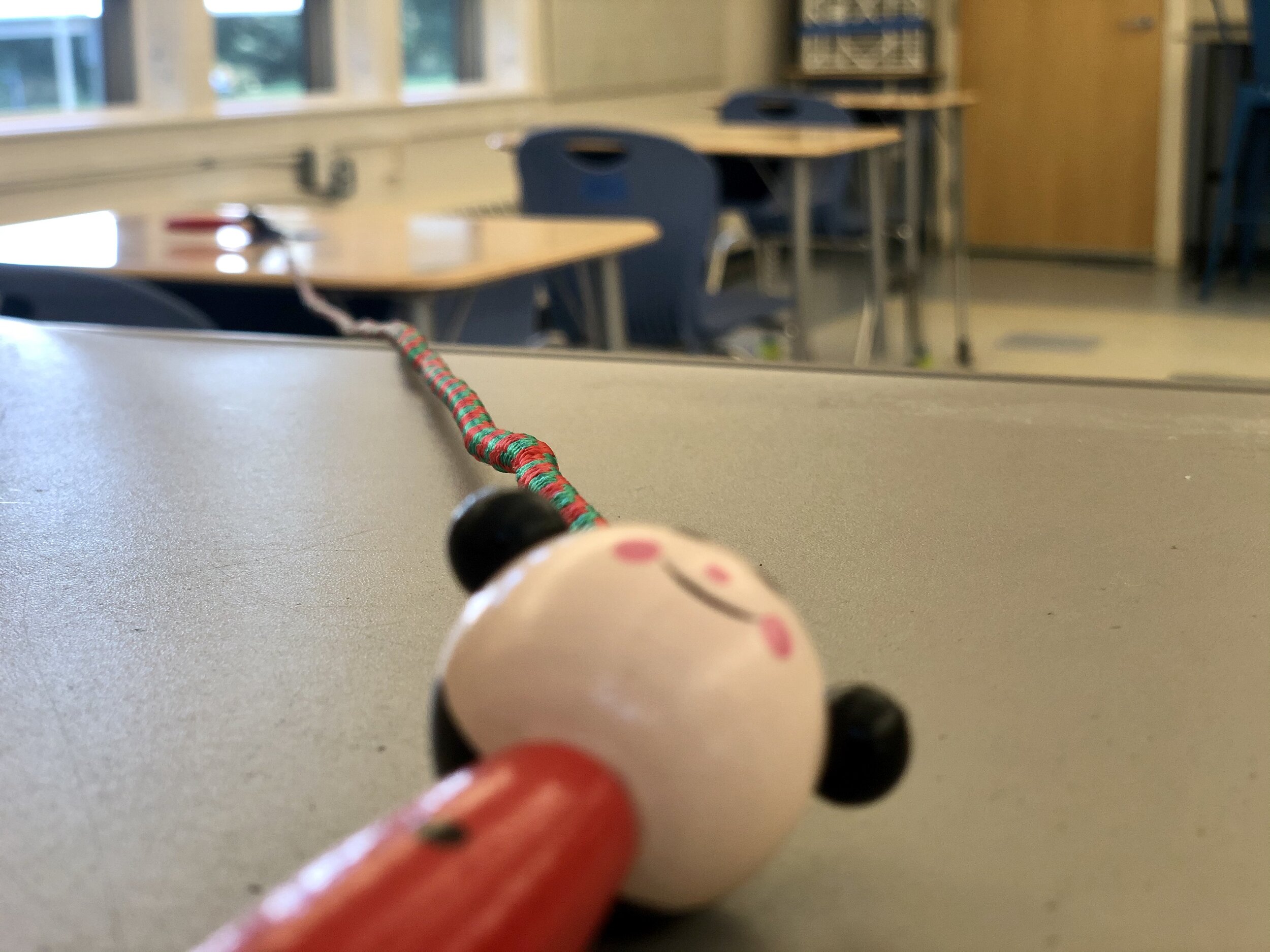

Our first-aid kits now contain jump ropes to measure the distance between the students’ desks, which must be six feet apart and all facing the same direction. Teachers must stay at the front of the classroom and avoid coming within six feet of a child for more than 15 minutes barring “extreme emergency.” I used to spend most of the day teaching in a low crouch, eye to eye with the triumphs and crises of childhood. This year, a third of my students will be eighteen feet away.

The nurse reads more guidelines: students may speak to and towards the teacher as long as there is ample space between them, as many windows open as possible, and fans blowing filtered air. Minimize head turning. “I don’t understand,” says the social studies teacher, “The kids can’t turn and talk to each other?” I see the nurse’s sigh, but I can’t hear it. “You’ll have to go outside,” she says.

Are kids allowed to browse books? Can they talk at lunch? Will they use their cubbies? The answer is no. No communal supplies. No carpets or stuffed animals. Do not enter the building until you’ve submitted your temperature, and schedule your weekly nasal swab. Absolutely no singing. The kindergarten teacher texts me three weeping emojis.

After the presentation, I have just one question: How will I enforce these rules?

My friend teaches in another state, and on the second day of school, his student fell 20 feet over the railing at the top of the staircase. My friend ran to him, and the other students crowded around shoulder to shoulder. Their classmate was inexplicably fine, but they were too close. After the boy went to Urgent Care, my friend had to scold the other students for not keeping their distance. He called me at the end of the day, both to relay the miracle and to confess his role in it: helpless witness, reluctant enforcer. I don’t have stairwells that tall in my school, but I will have the same story. I’m dreading the day I say, “stop singing.”

Last year, I asked fifth graders to brainstorm all the ways teachers try to get them to be quiet. The list grew quickly to over twenty teacher “tricks.” I’ve tried them all. I’ve counted down from ten, five, and three. I’ve rung a bell, a chime, and a bowl. I’ve tried call-and-response, raising my hand, raising my voice, and staying very, very quiet. Even when the students decided on which method I should use, nothing was truly effective until our building closed in March and I could press the “mute” button on Zoom. I began our first Morning Meeting in static silence, but quickly unmuted the kids. I already missed the rustling pages and tapping pencils, the noises bodies make when they’re bored. I refused to turn off yet another sense, and soon barking dogs, crying siblings, and working parents began to interrupt our lessons. By April, the eleven-year-olds were muting themselves.

I have my own list of teacher tricks. These are the slights of hand that camouflage the control at the core of my classroom, and I use them as much for myself as for the kids. I arrange the desks in a circle. It takes twice as long to pass out papers, but the students look at each other instead of me. I never designate a “front” of the room and constantly move as I speak. The students vote on their own rules and read-alouds. I allow hats in the classroom and talking in the hallways. When the task or the room or the day is too stifling, I give two choices: lie down on the floor, or go outside and run as fast as you can.

These choices offer a temporary respite from what school demands of both student and teacher. No matter how I arrange the chairs or what I put up to a vote, those decisions are still mine to make. My role is both fixed and false: I am in charge of people I can never completely control. Some days that power clings to me, and some days I cling to it. This year, when bending or breaking the rules is hazardous to our health, there’s no point in disguising them. At first I am scared. Maybe I can only be a teacher if I lie to myself about the constraints that my job depended on long before COVID. I’m also relieved. Before putting on my school-issued mask, I get to take off the one I’ve worn for five years.

I return to the building I left in March to arrange the classroom according to the new protocols. The playground is wrapped in caution tape. The water fountains are covered in garbage bags. I take pictures of everything; I’m obsessed with documenting each line and sign. Though I’m photographing what’s different, I recognize it all. When I look at the rows and partitions, I see the bones of the schoolhouse. The spine of this strange creature is my own.

The jump rope in the first-aid kit has ladybugs for handles, which I tape at the center of each desk to measure a six foot radius. After rolling up the carpets, I also tape an “L” at the feet of the chairs to designate their permanent place, and arrows on the floor to indicate the traffic pattern. I put the board games in the closet and set up my desk at the front of the room. For there to be sufficient distance between the students and the sink, I have to shove one desk into the far back corner of the room. I decide Elliott will sit there because she’s taller than most sixth graders and terrible at lying when she’s upset. To make it up to her, I put the pink goggles in her box of supplies. Then I punch out a window screen and stick a hummingbird feeder to the glass. We might not even be in school when the birds migrate north next April, but I want us to look for them anyways. When we wonder about the future, I want us to include their tiny wings.

Three days later, on the first day of school, Mario and Zoe come in a few minutes early. I turn around and find them haphazardly spaced in the doorway. I’d forgotten how tall the kids are — not very. I rush towards them, grinning a smile they can’t see and extending a hand they can’t shake. I step back and point to the arrows on the floor. The rest of the students arrive and sit immediately. No mingling, no dawdling, their bodies more still than when they lived online. I didn’t ring a bell or press a button, but still they are muted.

From the front of the room, I turn to point at the schedule and see Aaron’s face projected on the whiteboard. He will learn remotely for the year, and his mom is unsure if they’ve made the right call. Yesterday I received an email from her: “I told Aaron there’s no talking at lunch. He says he’d rather stay home.” He and I both stare at the silent rows. I’m not distracted by what’s different, but by what’s exactly the same. I planned this day like any other: After snack comes recess. After recess comes math. After months of glitching, it feels so good to go through the motions. It feels so good to feign control.

“Is this a little strange?” I ask. From the back row, Elliott says, “I haven’t been in a room with this many people since March. I don’t know what to do.” The other kids nod and fidget with their masks. I can tell them what’s for snack or what they’ll be doing at 2:00 this afternoon, but I can’t tell them what to do about that feeling. I feel it too. I reach for people and withdraw from them. I forget it’s not safe to share pens. The skin on my finger tips is peeling, and I keep trying to sip coffee through my mask. I want school to go back to what it was, and I want it to be completely different. From the front of the room, I don’t know how to approach them. I want to get closer, but I take a step back instead. “Look at this!” I say, pointing to the hummingbird feeder. They look and turn and talk.

Julia Juster lives in Cambridge, MA. She teaches middle school English, and is a Teaching Fellow at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. She was born in Cleveland, OH.