The History Nigeria is Fighting to Erase

“A war once fought never comes to an end,” my mother said. “The wounds crust over, but rarely ever heal.”

It was Nov. 2016, and I was visiting home to interview my parents and a few other relatives for a writing project I was working on — an essay about my family’s experience during the Nigeria-Biafra war, a conflict which ended this month fifty years ago with an estimated three million deaths, most of which were non-combatant civilians and children. What was intended to be a four-page essay snow-balled into a quest to find Nigeria’s hidden history and locate the story of my family which, unbeknownst to me, is intricately tied to it.

Biafra seceded from Nigeria on May 30th, 1967, after shockwaves of massacres in Northern Nigeria sent Easterners, mostly the Igbos, scampering back to their ancestral homelands across the River Niger for refuge. But the killings followed them into the new republic when Major-General Gowon, Nigeria’s military Head of State, declared war in July of 1967 against the breakaway state. Overpowered and internally weakened by a blockade, Biafra territories began to fall gradually to the federal troops. By the end of the second year, Biafra was already teetering at the edge of defeat with a displaced civilian population that its shrunken resources and territory could not contain.

My parents met in a refugee camp in Port Harcourt in 1969. And while the civil war was drawing to its end, they were hurtling into a hastily arranged marriage. My mother, an orphaned refugee, was barely fifteen. She had been forced to watch as a Nigerian soldier pumped bullets into her father’s body while Aba, a commercial city in the Southeast, was captured by Federal troops. Her father, a divorcee civil servant, was raising her alone, along with a 13-year-old cousin. The boy went missing in the chaos that ensured during the invasion — either killed or kidnapped. On a single day, her world whacked off its axis, thrusting her into a lone adult life nothing had prepared her for. Sixteen months later she’d sign herself off to a marriage that held promise of family — a support system she would need to face an uncertain post-war future.

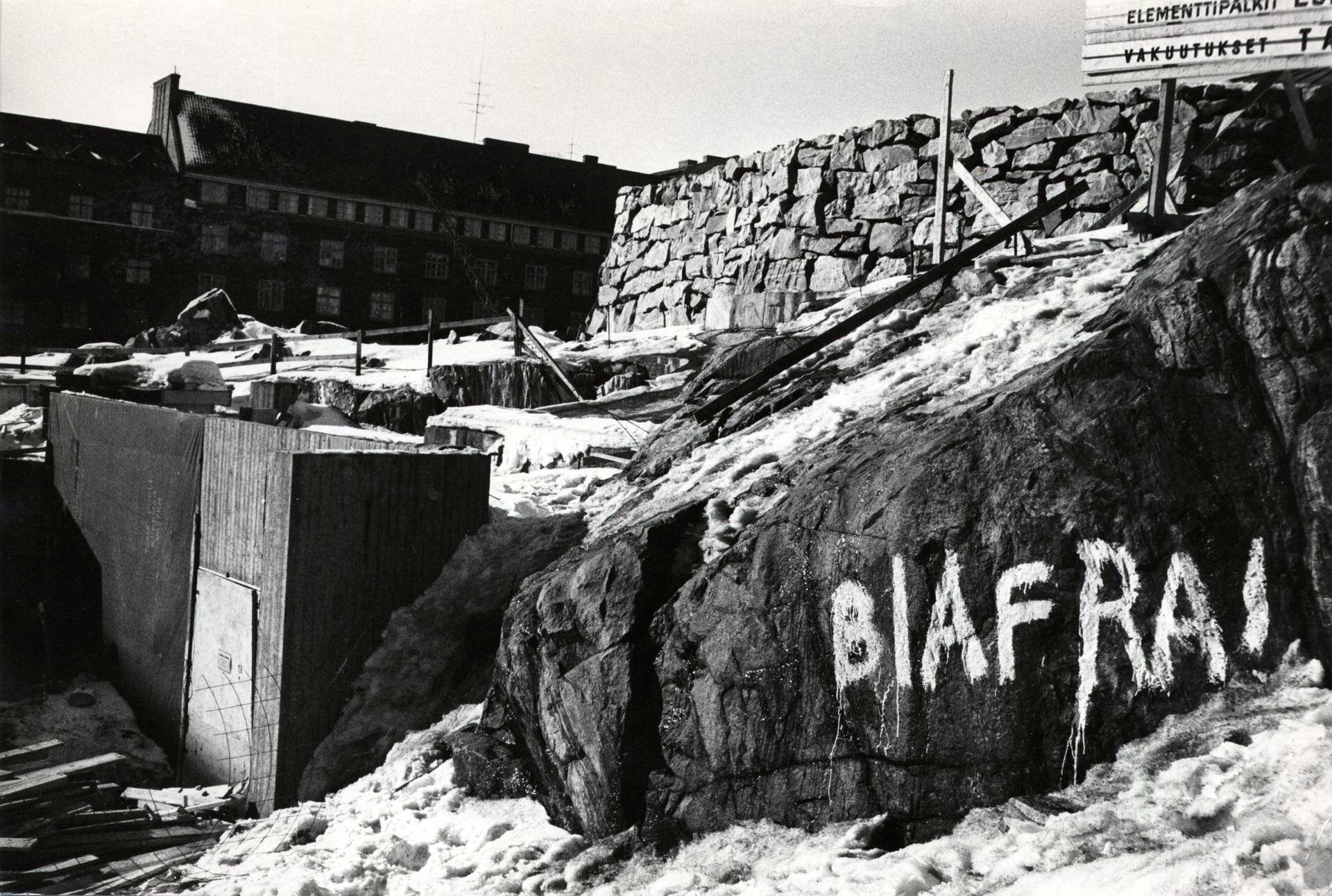

The Biafra war was fought in a tiny, landlocked rainforest region in West Africa, but it garnered massive international coverage owing to the works of photojournalists like Don McCullin who photographed the horrors of disease and mass starvation. Biafra became the first humanitarian disaster to be broadcasted on global television, and the images of severely malnourished children (known as “Biafra babies”) which came through TV screens into sitting rooms shocked the whole world and redefined modern humanitarian-aid. Those images and the reports that accompanied them are still as relevant as ever — they have over the years become a repository of memory and a reference point for the children of survivors who wish to understand a war that Nigeria has banished from its consciousness.

The people who lived through the war are shackled by their own trauma and five decades of paralyzing political fear. Growing up, the closest I came to learning about Biafra were from oblique allusions my mother made to it during conversations with her aunts. Twice or thrice she talked about living with nuns in a refugee camp, but none of those recollections registered as personal tragedies. In recounting them, she insisted on keeping them as impersonal as possible, wrapping her memory of horror with an emotional distance so palpable that the stories could have happened elsewhere and to people she didn’t know. Like most Igbo people who survived the 30 months-long war, my mother believed it was not proper to speak of her experiences.

When she gave birth to her first child in 1972, one of the names my mother picked was Echefula, an Igbo name which means do not forget. But there was already an unprecedented pressure on the entire region (fueled by the “no victor, no vanquished” mantra) to quickly get over their experience of the war. So instead, my brother was named GladStone, a name as foreign to the Igbo language my parents spoke as it was to their recent experience — Igbo people often name their children to reflect a profound experience or defining moment in the family’s history. A cousin born months after my brother would later take on the name, retaining the significance for the family.

The “no victor, no vanquished” was a post-war propaganda put up by the Gowon administration to impress the international community whose eye was trained on Nigeria. It not only earned Gen. Gowon’s instant praise; it gave Nigeria an undeserved moral advantage in the historicization of that war. Igbo people were cast as rebellious troublemakers — a tag that has been repeatedly used by successive governments — who didn’t deserve forgiveness but got it anyway. It stole attention from the pogroms of 1966, the massacre of 30,000 Easterners which led to the secession. It was a shallow and hypocritical approach to an issue that required deep remorse and honesty by a country too afraid to engage holistically with its own history. Where reparation, truth and reconciliation were needed, forgiveness was offered.

And, like all graces, forgiveness always come at a cost.

For fifty years, the Southeastern region has been paying the heavy price of being penitents. Their reintegration into Nigeria was contingent on how fast they brushed off the ashes of the war and severed emotional and philosophical ties to the short-lived republic. Recollections of injustices and demands for reparations were regarded as ingratitude and, sometimes, outright acts of treason. The Federal government also went to work, but surprisingly not to rewrite history as post-war nations are wont to do, but rather to uproot and erase it entirely from the national consciousness. The Bight of Biafra and Biafra Light — a coastline curve off the Atlantic coast and a high-grade crude oil produced around it — were renamed “The Bight of Bonny” and “Bonny Light oil” respectively.

Perhaps, the most bizarre of these gruesome attempts to erase memories of Biafra has been the erasing of Nigerian history itself from school curricula throughout the country. It happened when calls were ongoing for the national archives of the war to be declassified. For a multi-ethnic country like Nigeria, where allegiance is often pledged along ethnic and cultural blocks, most people believe that engaging with Nigeria’s collective history might be the only way to tease out a national story. But the atmosphere of hostility in which the government clamps down on opportunities for meaningful conversation makes such possibility increasingly unfeasible.

While traveling in a bus sometime in December 2017, a conversation between two passengers spiraled into a debate about the civil war. A woman begged that the topic be dropped. “Thess people might hear us,” she pleaded, referring to the soldiers stationed every quarter mile on highways all over Southeast Nigeria. That week, an army battalion had mowed down unarmed civilians protesting the invasion of Umuahia by soldiers in a military operation called Python Dance. Apart from the region being heavily militarized, every year memorial services for the more than 3 million who perished in the conflict are raided and shut down by the government.

Although the Nigerian government would rather believe otherwise, the civil war is not a thing of the past. Families still mourn their dead and nurse hopes of reconnecting someday with the missing. Like the 64-year-old woman I met in Frankfurt last July who still carries a picture of her missing twin sister. Several households hold space for their unaccounted relatives while drafting family wills and during land allocations. My mother’s uncle, for instance, came home in 2008 — thirty-eight years after the war. From time to time, landmines and ordnances explode, reminding entire communities of their recent history. One such incident occurred last month in a school, with students sustaining injuries.

I was born two and a half decades after the war. As a millennial, I belong to the generation unable to study an expurgated history of Nigeria. I should therefore not be interested in Biafra. But instead, I’ve been researching and exploring it in my writing. In 2016 I visited the location where my maternal grandfather was killed in Aba, scooping and taking a handful of earth with me. I brought it, together with a miniature flag of the defunct republic, to the US. There are no monuments anywhere in Nigeria commemorating the civil war or honoring the memory of those who perished in it, rather survivors have been piled with guilt and shame for trying to remember loved ones, and grieve an event that altered their lives in tremendous ways. These personal mementoes I carry do not just point me to the stories of my family and the struggle that made me possible, they keep me close to history itself, reminding me how easily our lives and stories can be erased by politics.

Chibuihe Obi Achimba is a poet and essayist from Nigeria, and a visiting poet at the Harvard University Department of English. His works have been featured in Guernica magazine, Adirondak Review, Expound, Heart Journal, Expound, Brittle Paper, and various anthologies, and have also been nominated for both the Pushcart Prize and Best New Poet. He was awarded the inaugural Brittle Paper Award, and was a finalist for 2018 Gerald Kraak Award.