I Bite My Tongue

Most mornings, when I wake my daughter up to go to school, she asks Why so early, mom? It isn’t fair. Some days she doesn’t want to go at all. I bite my tongue. I want to tell her how lucky she is, that there are millions of children who’d give anything to go to school. But she’s only eight and it’s six in the morning, and I haven’t had my coffee yet.

My parents believed in education. It was their best gift to their children. Everything I am, and will ever be, stems from a gift denied to millions because of war, because of violence. My father was an accountant, and my mother, a housewife. Financially, he was doing very well until the late seventies when inflation hit Uganda. With nine children to support, he — we — struggled. My mother farmed, made bricks, taking any job she could find which allowed her to work with her hands. Sometimes, we walked to school barefoot; other times, we attended boarding schools without pocket money. Somehow our school fees were always promptly paid. We had uniforms, pens, and books.

I graduated from Makerere University with a Bachelor’s degree in Law, followed by a Master’s in International and Comparative Law from the Free University of Brussels. It was there that I was introduced to human rights and refugee law: The notion that all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights stayed with me, just like the plight of refugees and internally displaced people. Once I graduated, I looked for work with Non Governmental Organizations and the United Nations, working in Uganda, Sudan, Tanzania, Sri Lanka, South Sudan, occupied Palestinian territories, Switzerland, and now at the United Nations headquarters in New York.

I have had many variations of the same conversation about school with my daughter. To listen to her, you’d think she doesn’t like school, on the contrary she does, and as soon as she’s had her shower, she’s good to go. It’s the waking up at six o’clock which isn’t fair. She tells me, “when I become school president, I’ll introduce three-day weekends, and summer holidays will be three months long.” I don’t want to tell her that she’d have to become the mayor of New York or something like that. But, I’d like to tell her that for some children, schools are their only protection from guns, from abduction, recruitment into armies. I’d like to tell her about my visit to Myanmar (which has stuck in my mind since I went there last year) where I accompanied my boss to understand the humanitarian situation there.

It was my first time to the country. Since August 2017, violence there displaced more than 700,000 Rohingya to neighboring Bangladesh. Prior to 2017, after violence erupted in 2012 between the Buddhists and the Rohingya and other Muslim groups, the government segregated the two communities to prevent further violence and reduce tensions. Hundreds of Rohingya were confined to camps in Rakhine state, and the segregation policy was planted. In December 2019, their case ended up at the International Court of Justice where Aung San Suu Kyi (who won the Nobel Peace Prize for her non-violent struggle for peace, democracy, and human rights) defended her country. In the first international ruling against Myanmar, the courts said the country must prevent its military or others from carrying out genocidal acts against the Rohingya.

We visited one of the camps, Basara, in central Rakhine State. It was afternoon when we arrived. We walked through the camp, sometimes on planks of wood that barely covered the black water beneath which was littered with plastic bottles, empty sachets, and rotten vegetables. We entered houses with low ceilings held together with bamboo, roofed with grass or iron sheets with reddish and brown patches. Women in floral dresses, skirts, and blouses, carrying half-naked babies, talked to us about their fear of the houses collapsing on them during the cyclone season, about the heat that made it impossible to sleep at night, about the lack of privacy. We saw partially collapsed houses, and it was easy to imagine them being swept away. But this wasn’t their main concern. It was the lack of citizenship and freedom; most Rohingya are by law deprived of a nationality. Men in sarongs wrapped around their waists told us how authorities have effectively banned them from town centers and ethnic Rakhine villages, and how they’re afraid for their safety given the inter-communal tensions. A week before we arrived, a pregnant woman had died during childbirth. She wasn’t able to get permission in time to go to a hospital.

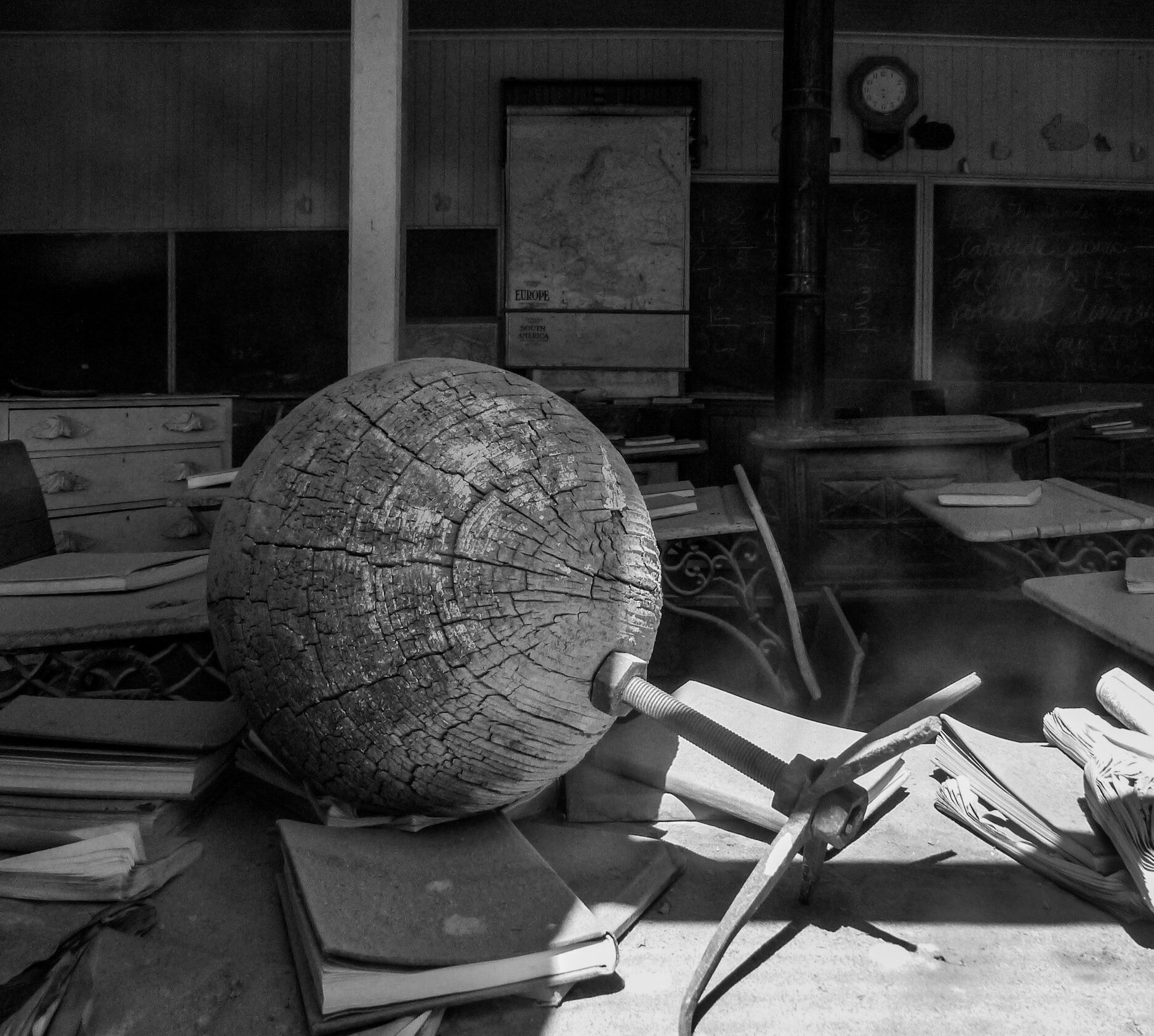

Somewhere in the camp, a young girl (she could have been 13 or 14 years old) approached us. She wore a white t-shirt with the words “Child Development Group” written in the middle, and UNICEF logos on her sleeves. Sweat was melting the thanaka paste on her face meant to calm and cool her skin in the hot weather. She was light skinned. She was a leader of the children’s group in the camp. With a soft, almost shy smile, her brown eyes pleading for help, she said, “I want to go to school. At home, I used to go to school. Here, there are no middle and high schools.” Citing safety concerns, school teachers and Rakhine communities do not allow children to attend the mixed government schools outside the camps. Some of these schools are fifty meters away from the camps. Official government teachers have refused to come to schools in Muslim villages. Then there’s the matter of poverty, the distance to school, lack of qualified teachers in the camps, and their fear of being attacked. From where we stood, we looked over the barbed wire along the wooden poles that cut off the village from where she was displaced. To be able to see your home, within walking distance, yet not be allowed to walk down the road to your own garden.

I only tell my daughter that many children can’t go to school.

“Why?” she asks.

“Because of war, you know, when there’s fighting, or a big storm…”

“Oh, I get it. When there’s a snowstorm, we don’t go to school.”

Ruth Mukwana is a fiction writer from Uganda. She is also an aid worker currently working for the United Nations in New York. She’s a graduate of the Bennington Writing Seminars (MFA) and holds a Bachelors degree in Law from Makerere University. Her short stories have appeared in Solstice Magazine, Black Warriors Review, Consequence Magazine, The Compassion Anthology, and Speak the Magazine.