Place of Rest

My partner Scott Harney died last spring, in late May. Cardiac arrest. For several years he’d been suffering from congestive heart failure, a pernicious side-effect of chemo treatments for lymphoma a decade before. CHF is one of those underlying conditions that present an ideal target for Covid-19. If Scott had lived and hadn’t caught the virus, he might have required hospitalization for breathing trouble, as he often did, with no beds or respirators available.

He was not afraid of death, he told me, and I believed him. His dying proved it. But could his resolve have withstood all this, his worry for me and everyone he cared about? For the world he loved “because there is no other,” as he wrote in a late poem? Right now, I’m glad he’s gone. Or maybe the crisis has wiped away my memory of what it was like to have him here.

Even before self-isolation, I was getting used to what the poet Elizabeth Bishop once called “personal silence,” the kind where you realize you’ve gone through a whole day, or even two, without hearing the sound of your own voice. Strictly observing social distancing, I do not visit my older daughter and her young children who live nearby. But I have been communing safely with the dead.

I live a fifteen-minute walk from Cambridge’s sprawling and seasonally verdant Mount Auburn Cemetery, America’s oldest garden cemetery and its first sizable landscaped public park. When Scott and I moved to an apartment near the cemetery in 2010, I was writing a biography of the nineteenth-century feminist Margaret Fuller, whose cenotaph is one of the cemetery’s prime attractions. (A cenotaph memorializes someone whose remains are buried elsewhere or cannot be found: in 1850, at age forty, Fuller and her Italian lover and son drowned in a shipwreck 300 yards offshore near Fire Island; only little Nino’s body washed to shore, and his remains lie beneath the cenotaph that honors all three.) I made regular pilgrimages to Fuller’s monument, seeking inspiration, often adding a stone or coin to the collection left by other devoted “Fullerenes” on the small shelf below her eroding limestone portrait.

But it wasn’t just my biographical subject that made the place familiar to me. In the 1980s, I attended the burial of Jenny Carroll, the infant daughter born prematurely to my friends Lexa Marshall and Jim Carroll, all of us taking comfort in the bright sun filtering through the arching branches of specimen trees on one of the saddest days of our lives until then. Although I wasn’t present for the interments, other friends have buried family members and spouses on the grounds since then — Janna Malamud Smith her parents Bernard and Ann, Gail Mazur her husband Mike, Fran Malino her husband Gene Black. I have visited them all, including most recently my predecessor in Fuller biography Joan von Mehren, buried last December next to her husband Arthur, a legal scholar at Harvard Law School, in a family plot not far from the section reserved for Harvard’s college professors.

In January, I decided to buy a plot for Scott’s ashes, one with room for mine too when my time comes. I’d been keeping the green plastic box from Stanton Funeral Service in the livingroom cabinet where he stored his CD’s — a vast collection of renaissance lute and viol music, every Leonard Cohen and Paolo Conte recording ever made — thinking I might one day scatter his ashes in Naples, his favorite Italian city. But I’d kept up my ritual walks to Mount Auburn, paying my respects to Margaret Fuller, who in the end had brought me a Pulitzer Prize, and climbing the tower at the top of the cemetery’s “mount” to admire the view over Harvard stadium to Boston and its ever-rising skyline. I decided to keep him near.

The cemetery’s sales rep didn’t hesitate to warn me that Mount Auburn’s prices are the highest in the country. His explanation: they’re building an endowment to maintain the park when all the plots are filled, perhaps forty years from now. I didn’t hesitate to sign over $16,000 for a square of lawn and a rectangle of granite on a communal wall with space for the inscription I had in mind, at the back of the cemetery in a newly landscaped section called Birch Gardens. Scott died at 63 before withdrawing a cent of the 401K he’d worried might not cover his expected years of disability. The plunging stock market has not caused me to doubt the investment.

Scott’s ashes are still in the CD cabinet, awaiting a day in spring or summer or fall when our families can safely gather and see him into the ground. But I walk to the cemetery often to visit our plot, and its remote location has set me on new paths, finding new and old friends among the dead, taking heart from inscriptions and comfort in what I know or can discern of deaths faced fearlessly, or simply faced.

There is Robert Gould Shaw, the Civil War hero who died at 25 leading the doomed Massachusetts 54th into battle at Fort Wagner; Julia Ward Howe, whose “Battle Hymn of the Republic” Shaw and his black volunteers sang as they marched; Charles Sumner, the abolitionist Senator who barely survived a brutal caning by a Congressional colleague four years before the war broke out and died still suffering from his injuries a decade after Appomattox.

There’s an honor role of accomplished nineteenth-century women, some of whom played bit parts in my books: Hannah Adams, historian, and in 1831 the first person buried in the cemetery; Harriot Kezia Hunt, the first American woman to practice medicine professionally; Dorothea Dix, crusader for the mentally ill; Harriett Jacobs, author of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl; the sculptor Harriet Hosmer and actress Charlotte Cushman, whose overlapping amours drew sculptor Edmonia Lewis, whose statue Hygeia marks Dr. Hunt’s grave, into their orbit. The flamboyant cross-dressing Cushman’s obelisk rises higher than any man’s in the cemetery; she was known as well for having submitted to two painful operations for breast cancer, “excisions” by scalpel and caustic. She was not cured.

There are touching memorials to young children, Jenny Carroll’s companions, often marked by lambs or cherubs. I’m fond of a tiny cross with a single name, “Freddy.” There are whole families with identically shaped stones, seeming to have died all at once, though a closer look at the inscriptions reveals otherwise.

In recent weeks I’ve discovered the grave of the historian Francis Parkman, another denizen of the nineteenth century to whom I owe a debt of gratitude — a prize given in his name helped my first biography find an audience and brought me a teaching job. And more gratitude still goes to David McCord, buried in 1997 at age 99 down the hill from Charlotte Cushman’s obelisk. In the late 1930s McCord, a poet and Harvard fundraiser, recruited my father, a promising California public high school senior, with an offer of full scholarship. My father failed to graduate and returned to his home state, but his stories of life on the East Coast drew me to New England for college, and I stayed. I would not be walking in Mount Auburn cemetery if it were not for David McCord’s long-ago benefaction.

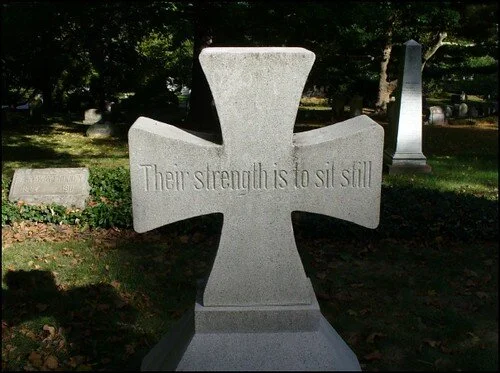

Today the bright sun of early spring illuminated a sturdy lichen-spattered cross I’d never noticed before, marking the grave of Susan Ruggles Welbasky and bearing the legend: “Their strength is to sit still.”

“Who is they?” my younger daughter’s boyfriend texted back from the Brooklyn apartment where both were working from home. I couldn’t answer, but with sheltering in place our only defense against the invisible menace, I told him I felt like one of them. Back home I found the line in the Bible, Isaiah 30:7—“For the Egyptians shall help in vain, and to no purpose: therefore have I cried concerning this, Their strength is to sit still.”

This afternoon I’d also visited the poet Robert Creeley, and in the same full sun studied the poem etched on his stone. The message was similar, minus the tears:

Mount Auburn’s grounds in early spring are barren, sere. The light strikes with cruel intensity, not yet softened by the leaves of shade trees: maple, ash, willow, and oak. A walker here retains, in Wallace Stevens’s phrase, “a mind of winter.” For now, this feels right. But the bloom will come, of virus and vine. So, too, the time to bury my partner beneath these words, from Robert Lowell’s “Obit” — “the lily, the rose, the sun on brick at dusk.”

_________________________________________

Scott Harney’s book is available here:

www.arrowsmithpress.com/scott-harney

Megan Marshall is the winner of the 2014 Pulitzer Prize in Biography for Margaret Fuller. She is also the author of The Peabody Sisters, which won the Francis Parkman Prize, the Mark Lynton History Prize, and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 2006, and of 2017's Elizabeth Bishop: A Miracle for Breakfast. She is the Charles Wesley Emerson College Professor and teaches narrative nonfiction and the art of archival research in the MFA program at Emerson College. Most recently, Megan edited The Blood of San Gennaro by her late partner Scott Harney, published by Arrowsmith Press (2020).