Covering the Head to Save the Head

SS is a diminutive Tamil-Muslim woman from Sri Lanka with a cherubic face, a tranquil smile, and diaphanous eyes. You can’t miss these features because, unlike women of her community, SS does not wear a veil.

I met SS for the first time at a cavernous home in a leafy upscale neighborhood of Colombo in 2017. Despite the dilapidated windows and fissured paint, the home, a historical heritage site with architectural details from the turn of the century, holds a firm carriage and a proud history. I walked past a maze of scaly ferns and luxurious bambusa grasses and imposing Cyprus trees while listening to paradise flycatchers and emerald bee-eaters calling their polysyllabic cries. SS knew of my interests in talking to and helping disenfranchised women. We ambushed a hug and sat down on the patio, sipping cardamom-rose tea.

The house was a haven for disenfranchised women and their children that SS and her mother, a fully hijabed woman, ran. The building’s second floor was reserved for paying guests for whom her mother cooked on-demand. The money thus collected was used to support the bustling life on the ground floor, which sheltered well over a dozen women and children, all of whom had fled domestic violence. And that first floor was pure magic — with group classes and lectures aimed at female empowerment, non-violence, forgiveness, life skills, creativity, and reinventing shattered identities. The children in the home, well fed and let loose, played hide and seek in plain sight.

SS was born and raised during Sri Lanka’s devastating civil war. She understood brutality before she knew her alphabets. She’d grown up hearing of killings during the thirty-year civil war that tore the country — Singhalese against Tamils, Tamil against Sinhala, Tamil Tigers against Singhalese Lions, Jaffna against Colombo. This ethnic conflict was about balance of powers, and while the majority of the Muslims in Sri Lanka were Tamils, this bloody history largely left the Tamil-Muslim community out of its violent civil war. So, only miles away from the horrors of Jaffna (which witnessed thirty years of suicide bombings) civilian killings, failed peace talks, multiple assassinations, 300,000 displaced persons, and over 100,000 deaths, her Tamil Muslim community stayed under the radar.

War came into SS’s life in the form of the battle of the sexes. In 2009, SS found herself a victim of domestic violence, under siege in her own home. Fearing for her life and the life of her then-unborn child, she fled to take refuge in the multiethnic city of Colombo.

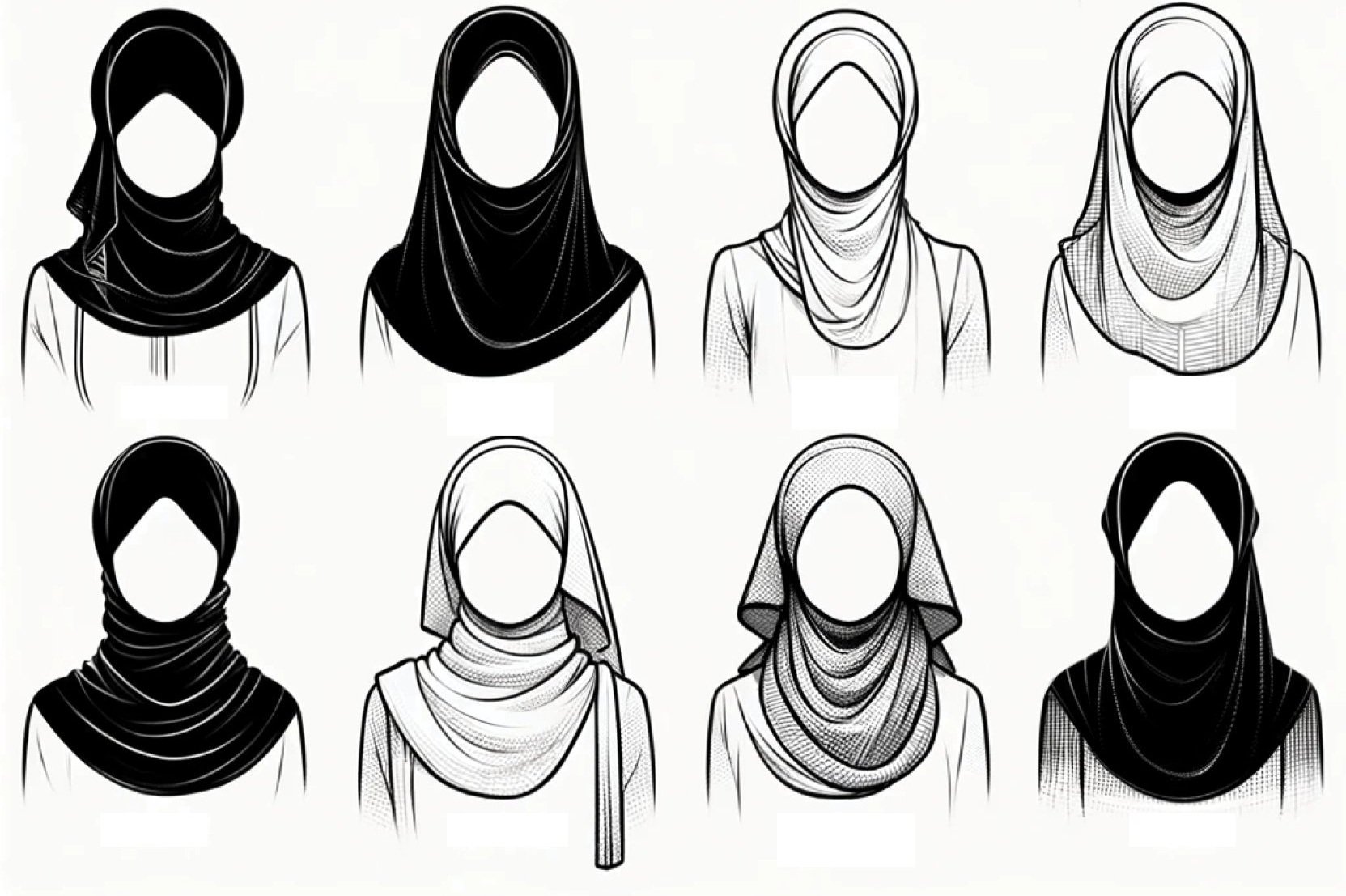

But SS was not about to drown in the silent sea of battered Tamil Muslim women. Instead, she dived into war-related recovery work in the form of helping other women. It was during this phase she took stock of herself and reevaluated the seemingly immutable laws of her community. First, she took the bold step of openly criticizing it for forcing women to hide their faces beneath a veil. She uncovered her head. “Not from defiance, mind you,” she said, “but from respect and love for my community, for my culture, and my religion. I don’t see how a veil defined the tenets of Islam. Or how it’s absence made you an apostate.”

She was swiftly excommunicated. But SS was equally quick to find her inner voice. She began writing poetry, publishing books about her experience of male domination, misogyny, and abuse. Her avid readers were not Muslims nor Sri Lankans nor Buddhists, who became her ardent detractors. Her readers weren’t the Tigers either. To her great surprise, SS discovered her primary audience among the displaced Tamils who had themselves fled the country and were living as ex-pats all over the world. In her they recognized a kindred spirit. Her admirers also acknowledged that only a true believer and a genuine insider could become a persuasive spokesperson for positive social changes.

In 2012, after receiving numerous death threats from even the most trusted members of her Islamic community, SS was forced to flee the country. For safety reasons, I cannot disclose where she stayed, or who or what organizations supported her. After three years of living in exile, she returned to Sri Lanka, determined to help abused women. Having experienced firsthand the horror of becoming marginalized — her interest in female subjugation reached beyond religion and ethnicity and politics and identity. Her altruistic goals became increasingly secular.

“The disenfranchised look the same all over the world,” she said. And this is how the historic (if bedraggled) house I visited in Colombo became the country’s first shelter for battered women from all walks of life — Hindu, Muslim, Christian, and Buddhists.

“My community will have nothing to do with me,” she said. “As long as my head is uncovered, I am dead in their eyes.”

SS asked her mother to join us. The mother was an imposingly tall woman but covered from head to toe, hence her internal metrics could only be guessed. She hesitated, and stood at the threshold, the back of her head gently tapping the swinging door, but with further persuasion she grabbed a kid’s chair to sit on.

SS put her arms around her mother. “The saddest part is that my community of Muslim women have no idea that the head covering is used as a tool to subjugate and diminish women. We end up having a conversation about the immutability of this practice, when nothing of this rigid nature even existed a few decades ago. Sadly, the most willing victims are the women themselves.” SS poked her mother with a pointy finger nail. “See, I love her dearly, but she sees what I go through without my head covered. She supports me 100 percent, but she wouldn’t dare uncover.”

Her mother’s only words were, “I keep my head covered so that my daughter doesn’t lose hers…”

SS laughed like someone had secretly tickled her.

“Our Muslim women swallow this form of oppression in the name of culture and religion, wholesale,” SS said. “This is truly a victory for our men.”

~

Post-civil war, after an uneasy truce was signed in 2009, Sri Lanka was starting to become a unified and undivided country, but small skirmishes of religious and sectarian violence began breaking out.

This uneasy patina was soon tarnished by news of home-grown acts of terrorism, which were perpetrated by some fringe groups of Muslim extremists against the local Sri Lankans, particularly the Buddhists. In 2016 there were reports of prominent Sri Lankan Muslim families becoming radicalized under the influence of Al-Qaeda and ISIL. Then came news of widespread openings of Madrasas. The Sri Lankan government, which was struggling with post-war recovery, found itself powerless against foreign support for Islamic fundamentalism within the borders of their country.

There were other signs that a major terrorist attack was going to take place. Partners who shared intelligence with Sri Lanka felt that there would be a retaliation for the NZ bombing where Muslims were killed by a Christian shooter on Sri Lankan soil. Despite this, a major intelligence failure on the Government’s part lead to a major terrorist attack. On Easter Sunday morning in 2019, nine jihadist suicide bombers — eight men and one woman — killed more than 250 and injured roughly twice as many. The bombing targets appear to have been chosen for their links to liberalism and western ideals, and was purportedly meant for International visibility.

Post Batticaloa bombing, the local terrorist outfit (called National Thowheeth Jama’ath (NTJ) — a home grown terrorist organization) claimed responsibility for the bombings. As the organization didn’t have the resources to pull off such a sophisticated, multi-pronged operation, the facts pointed to intervention by a foreign entity, most probably ISIL.

The Sri Lankan government, wanting to skirt responsibility for their glaring security failure at the Batticaloa bombing, started capitalizing on the public resentment for the already marginalized Muslim community in the country, and launched a scapegoating campaign against Sri Lanka’s peaceful Muslim population. The Sinhalese Buddhist nationalists waged a campaign of violence and hate, as the weakened and divided political leadership catalyzed the abuse.

Absurdly enough, SS found herself caught in the middle of this predicament: The “Safe Haven” she had created to help women and children was shut down by the Sri Lankan government, who’d become suspicious of her secular interest as a Muslim woman. At the same time, the Hindus, Christians, and Buddhists did not want her in their midst either. She experienced constant harassment from all directions. Under pressure from the international community, the Islamic fundamentalists wanted to distract the government’s attention from themselves. They turned their focus to SS.

In April 2019 a ban on burqa and hijab was issued in Sri Lanka, thereby escalating a debate within SS’s Muslim community. She found herself the target of constant threats against her life once again. She had become a liability for all groups: those for whom she was too Muslim and for those to whom she was not Muslim enough. The group she dreaded most, however, were her recently radicalized Muslim brethren who began issuing death threats, not just against her; this time her young son was targeted as well, and he had to be pulled out of school. Her mother had to go under cover. The Batticaloa incident came back to haunt SS in the most preposterous of ways, and she reached out to me for help in fleeing the country again.

Caught inside the cacophony of fervent Tamil nationalism, Islamic fundamentalism and Sri Lankan chauvinism, she was again ostracized — all because of her firm belief that covering her head had needlessly become a toxic issue.

SS had to flee overnight with her young son.

I saw SS recently, once again living in exile and looking for permanent refugee status. She was seeking help to resettle herself and her son.

With inky scholarly eyes, her young son put aside his math worksheet, slid the pencil behind his ear, and snuggled in her lap. There was not a hint of sadness in either of their faces.

Quaking with laughter, SS said: “They are trying to bury me, not knowing I’m a seed.”

Thaila Ramanujam is a physician in private practice in California. Raised in a literary family as the daughter of a prominent Tamil author, she developed a passion for Immunology early on and moved to the University of Washington to pursue research. She writes both fiction and non-fiction, and her work have been published/ or won awards in Nimrod, Asian Cha, Glimmer Train, and Readers. Her translations have appeared in International Literary Magazines. She is a columnist for a Tamil literary magazine, Kalachuvadu with international readership and has an MFA from The Writing Seminars at Bennington College, Vermont.