Grow Old and Be Strong

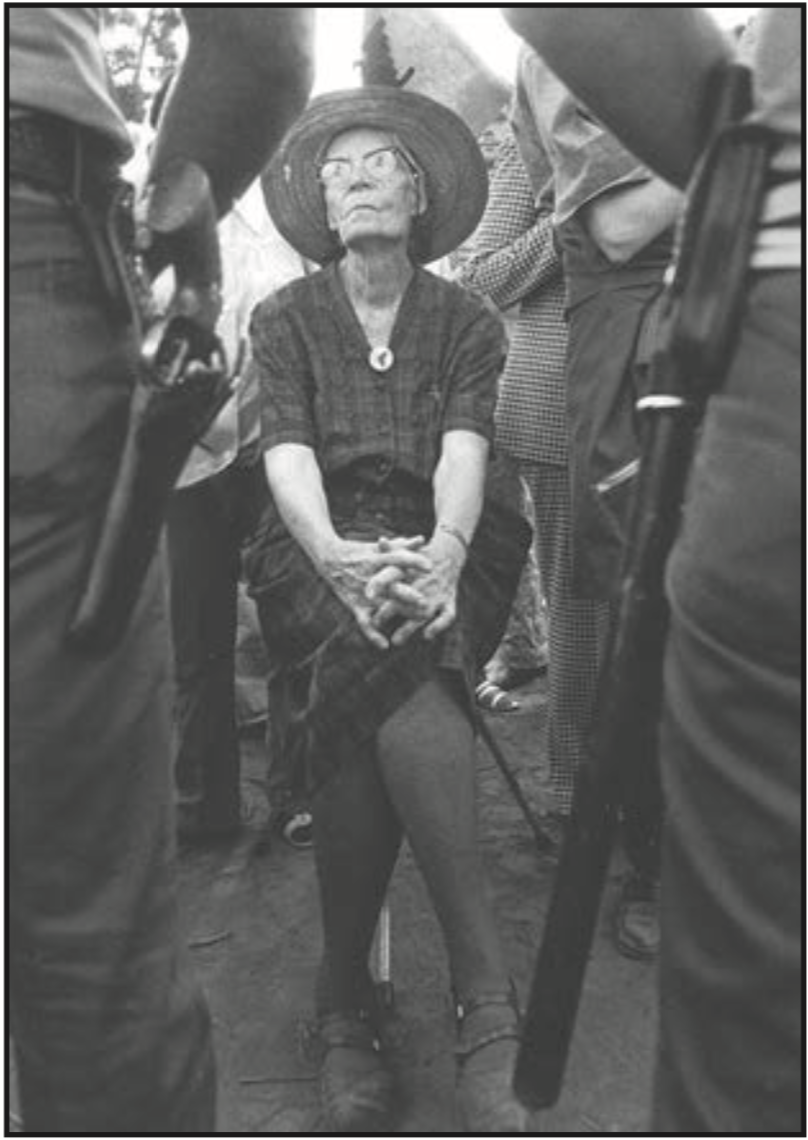

This photo of Dorothy Day about to be arrested came to mind as Catherine made her way down the road to face arrest.

Bob Fitch photography archive, © Stanford University Libraries

As she slowly walked toward the judge with the assistance of her ever-present cane, my 85-year-old wife Catherine, though bent with arthritis, was as fierce as ever. I am not saying that she was not nervous. On the contrary, she was having the same human reaction all of us have whenever we have to stand before a judge and explain ourselves, whether for a traffic violation or murder.

Calm on the outside, her stomach was doing flip-flops on the inside. Would she get the maximum sentence of six months in prison, would she get four months like I did in 2016, would she get one week like Tensie Hernandez from the Guadalupe Catholic Worker did last year? This is the day of reckoning, even though you have been here scores of times before, it never gets easier. The courtroom is designed to elevate the regal, berobed judge on a dais, and diminish the lowly, frightened defendant.

Before Court began, we talked about U.S. Attorney Sharon McCaslin. Sharon is our own “personal” Federal prosecutor, not unlike the character, Inspector Javert in Victor Hugo’s novel, Les Misérables, she is determined to pursue and prosecute Catholic Worker miscreants to the full extent of the law. Over the years she has prosecuted us more than 20 times, even up to the U.S. Supreme Court. She is always prepared to list our innumerable crimes against the state, from blocking the downtown L.A. Federal Building front door to pouring blood and oil on the steps of the Federal Building, to delaying expensive missile launches. She never fails to insist on the maximum sentence: “They won’t pay fines, they won’t cooperate with probation, they refuse community service. You might as well put them in jail.”

As Catherine stood in front of Judge Louise LaMothe, with her fearsome facade and flip-flopping stomach, I was reminded of the day last August 6, Hiroshima Day, when Catherine decided that she would cross the green line painted on the road at the entrance of Vandenberg Air Force Base and risk prosecution for trespass onto government property.

We travelled to Vandenberg, as we had for the last 20 years, to protest against nuclear weapons and their delivery systems that are routinely tested there. Periodically nuclear delivery systems, or to be a bit clearer ICBM missiles with non-explosive depleted uranium warheads, are tested by firing them down range in the South Pacific approximately 5,000 miles to Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands, not far from where the U.S. tested hydrogen bombs in 1946. The islands, where the original inhabitants once fished and gathered fruit, are now uninhabitable, polluted with radioactive waste.

The cost of maintaining and testing these delivery systems runs into the billions, and we are now spending more than one trillion dollars on upgrading our nuclear arsenal, using much needed dollars urgently required for the health and welfare of the nation and its deteriorating infrastructure.

These thoughts ran through my mind as I watched my 85-year-old wife with her arthritic knee, bad back, and white hair gleaming in the sun, hunched over her red three-wheel walker as she pushed towards the line of twenty Military Police dressed in full riot gear: knee pads, chest pads, crash helmets with face masks pulled down, steel batons at the ready.

Catherine normally, out of self-reliance and a bit of vanity, refuses to use a walker. But in this case she was fortunate there was one available because in order to be arrested she had to walk about 200 yards towards the police line, not something she could accomplish using just her cane.

There was not a dry eye in the crowd as we sang Carry It On. “There’s a man by my side walking, there’s a voice within me talking, there’s a voice, within me saying, carry it on, carry it on...” as Catherine walked toward the police line and arrest. Many of us in the crowd were no doubt reminded of the famous Bob Fitch photo of 75-year-old Dorothy Day on the picket line with the United Farm Workers Union in Delano, California, just before she was arrested for violating a court injunction prohibiting picketing. Dorothy, a harmless looking senior citizen, sitting on a stool wearing her straw sunhat and thrift store house dress with a hand-sewn patch pocket for her “hankie” is framed by two uniformed police officers in riot helmets with their pistols and batons highlighted ominously in contrast to this obviously frail, but fierce, elderly woman.

Five years ago, for her 80th birthday, the photographer sent Catherine an autographed copy of the photo of Dorothy on the picket line at Delano, writing: “Grow old and be strong, Happy Birthday Catherine.”

My musings were disturbed when the court clerk called the court to order and stated: “The United States of America versus Catherine C. Morris, case number cc21-9366503, please come forward and state your appearance.” Catherine indicated to Judge LaMothe that she wished to represent herself.

The judge then asked the prosecutor to tell Catherine what the maximum sentence for her crime of trespassing could be: “The maximum penalty the court could impose for this violation is a term of imprisonment of six months, a fine of up to $5000... and if probation is imposed, it could be a term of up to five years.” Catherine pleaded guilty. The Judge then told her that before sentencing she could make a statement.

Catherine spoke: “Well, it is known that the date of the citation is August 6, the commemoration of the bombing of Hiroshima, and so we closed our soup kitchen so that we could come up to Vandenberg for the planned protest. Know that I really hate to close the kitchen because it deprives anywhere from five hundred to a thousand people from a very good hot lunch, but we did it because of the importance of the event.

“But then while I was standing there at Vandenberg, I was thinking about the people who live on the streets of Skid Row in Los Angeles, and it brought to my mind my disapproval and disagreement with the budgeting of monies by the United States, that while half of the money collected in taxes goes to military expenses, citizens of this country sleep on the streets because there is inadequate care and human resources available. With that thought in mind, and also this thought mind — it is not up to us to fix everything, God initiates breaking into the chaos with blessings. And I thought, what blessing can I take home to the people on Skid Row, to the chaos they live in?

“I did not have a lot of choices, but I thought the least I could do is walk down the road to that line (of Police) that are waiting for someone to cross the line, and so I did. The people who eat at our kitchen know that we are activists, and know the kind of risks we take, and they consider it a blessing that we are there.”

After Catherine finished speaking, a hush fell over the court. I restrained myself from clapping. The judge thought for a moment but imposed no prison time, no fine, only a five-dollar “processing fee” and a ten-dollar “special assessment,” which Catherine will not pay. Ω

(This column first appeared in the December 2019 edition of the Catholic Agitator. Reprinted here with permission of the author.)

Jeff Dietrich is a founding member of the Los Angeles Catholic Worker, a lay community dedicated to progressive social justice work and part of the Catholic Worker movement founded over 80 years ago by radical Catholic thinker and activist Dorothy Day. Since 1970, Dietrich has been committed to the care of homeless, poor, and marginalized people on L.A.’s skid row. He has been arrested for acts of civil disobedience more than forty times. He has written about his political beliefs and the experience of poverty for the Catholic Agitator newspaper for more than forty-five years.