Serendipity: Notebook

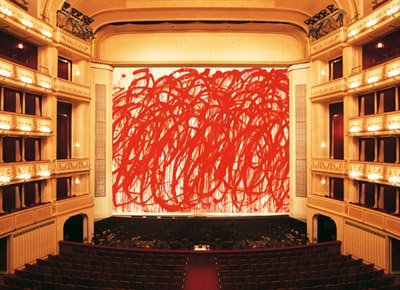

“Bacchus” Cy Twombly, Eiserner Vorhang in der Wiener Staatsoper, Saison 2010/2011

Copyright: CC BY-SA 3.0 de

Serendipity is glimpsed in its myriad little occasions, but for me the point is really the subtle and variable current that enables them. That current gets active, I think, when there is heightened attention, whether having to do with the affections, or else making and creating, the efforts of the imagination. Is it that I unexpectedly find what I need when I am writing, or does my raised energy reveal the relevance of what I am already looking at? When I’m taking pictures, I often have the experience where I’ll staring at something right in front of me, something I’ve looked at a thousand times, and suddenly I see it. At which point, because of the seeing, through the seeing, that familiar thing becomes picture-worthy. I reach for my phone.

~

Ernst Gombrich, in his Art and Illusion, writes: “What we read into these accidental shapes depends on our capacity to recognize in them things or images we find stored in our minds.”

Well, this is the interface, isn’t it? The mind projecting its stored business upon things in the world. Not just any stored business, but that which is in some way salient, charged. So the anxious soul finds premonitions, and the yearning one reads maps of love. Though I’m sure it’s not that simple. So far as coincidences and serendipities are concerned, it would follow that we screen the incessant swarms of impressions, flagging what seems especially to concern us.

~

Growing up, I spent a huge amount of time roaming. Prowling woods and swamps and farms near our house, collecting and sifting. I was close to the ground and everything was interesting. I wanted to understand what was what — it was that basic. I was also reading mysteries — Hardy Boys mostly — and of course I wove that amped-up sense of evidence and clues into everything.

The difference between myself and a detective was that a detective works a case and the clues eventually disclose their causal/empirical relation — the mystery is banished as the case is solved. I had no case, but I was thrilled to be looking for clues.

~

With the idea of finding comes the necessary idea of losing. If you’re not lost, you can’t be found, and if you don’t know what you’re looking for, you don’t really find it. Several things have come to mind related to this. I think of Poe’s “The Purloined Letter,” which plays with this idea. The story turned on a search for something — the letter — which was in fact in plain sight the whole time.

There’s losing something and seeking it, but then there is the condition of being lost. And there’s also losing and finding as they pertain to memory and the unconscious. In the outer world, things can truly be lost, as when something falls out of your pocket and is never to be seen again. Things are also misplaced — I lost my wallet! — and located again.

Misplacing is what brings mind-state — mental functioning — into the picture. Misplacing is the result of inattention, where the mind was ‘somewhere else,’ or forgetting. What is forgetting?

The inner — mental — part of this is a whole other dimension. In that realm, things can be misplaced, forgotten, or pushed out of view, but they are somewhere on the premises and we can usually get them back, whether through active recollection or some kind of fortuitous retrieval. We all experience this, don’t we — those of us who are older, especially — the delayed reaction recovery. I will search for something I know that I know, a person’s name or a word, and when it won’t come I usually step back. I stop working actively and trust the inner recover process, which mostly works, but seldom on cue. The party ended hours ago, but there I am” “Deborah! That was her name!”

~

I went to take a walk in the woods this afternoon, iPhone in my pocket in case the world started to seem photogenic, which it does sometimes. But there was finally not much, a few of those ‘almost’ moments when I stopped, took a backward step to double-check something that was there in the corner of the eye — a protruding root that looked like a miniature owl, the glow of tree-filtered light on a patch of fine, thin grass — but nothing that felt quite right…Still, those near misses did get me thinking of a book I’d bought a few years ago — Sally Mann’s Remembered Light: Cy Twombly in Lexington. An odd item, but one I do pull out from time to time when I want to have a certain kind of looking session.

It’s not just the mind that sometimes wants to come off its tether — the eye does, too. When this happens I like to put myself in front of something — a painting, a photo — and just follow the drift. I must have been feeling the need, because as soon as I got home I found the book and sat down to look at it again.

Looking — at times it feels like I’m thinking with my eyes. There are so many different intensities — from passive absorption, to sustained focus, moving back and forth within the frame, questioning, registering tensions, shading back off into reverie.

Mann’s book — for me — gets about as close as possible to the photographic apprehension of what is finally not to be captured. This might need a bit of explaining. Sally Mann and Cy Twombly were, as we know, old and close friends. They seemed, if this is a real word, telepaths, seeing eye-to-eye, and communicating in aesthetic code. Mann had been a frequent visitor to Twombly’s studio, and when her friend died she had the impulse to memorialize — as who does not? Her way of doing this was by taking pictures in the studio he left behind.

But that sounds too matter-of-fact. The business is more interesting and I want to find the right way to get at it.

I am no expert in the work of Cy Twombly, but in my mind he is an artist pledged to the fortuitous, to visual intuitions that jump ahead of sense-making endeavors — a master of the luminous scrawl, the tell-tale smear — and who is going to interpret the work, except to say it registers on the retina in an epiphanic corner-of-the-eye way? So I’m thinking of Twombly on the one hand, and then of Sally Mann looking to invoke — and celebrate — her friend by seeking after his traces.

This is a bit vague, but one does not run a straight course to the ineffable. Let me try to get at it this way. I remember Flaubert writing in one of his letters that he dreamed of writing a book about nothing. ‘The most beautiful works,” he wrote, “are those that have the least matter; the closer expression hugs thought, the more words cleave to it and disappear, the more beautiful it is.’ What Flaubert says about verbal expression, I want to apply to the visual. If words can verge on thought, then maybe light and shadow can get us close to…mood, to the feeling in the room, or, more precisely yet, to the feeling that had been in the room. The title is, after all, Remembered Light, and the phrase is taken from a poem by Mark Strand, from the lines: “When the weight of the past leans against nothing, and the sky/Is no more than remembered light.”

Light, in this configuration, is time itself. And doesn’t everyone who takes photographs, who writes with light, have that feeling sometimes: that the light on that branch, that wall, marks a moment — once and never again — and that to get it on film is to honor that? But I think that what Sally Mann is after is even more elusive than that presence. She is trying to evoke the memory of presence.

We know that a room can hold some vibration, some echo, of what happened there — the plates and glasses on the table, the rumpled covers on the bed. Things give us back some sense of the use they were put to. So the studio of an artist like Twombly, especially as it is filtered through the sensibility of a photographer as attuned to atmospherics as Mann, will resonate. And, I would add, resonate all the more as the images are felt by us to be ambushes, inspired side-swipes, as opposed to more intentionally framed moments. Then, truly, we have the sensation as we look that there is something just outside our field of vision.

I turn the pages, taking in the shadowy corners, the blurred swipes of window-light on the walls, the paint-flecked floorboards, and the casual still-life of flattened tubes of paint and brushes — all the things that would count as evidence for the detective if the crime were the making of art.

~

In my younger and more hubristically optimistic days, I thought that I would spend my later years learning ancient Greek, as if the real stuff — the true perception — could be found there, in the epiphanies that can still be felt through the earliest word-coinages.

I wonder if part of my pull toward these ideas of earliness has to do with the fact that we are living in late-ness, post-modern and post- much else — all of us wrestling collectively with the sense that so much has been done and said, looking to answer the artistic question of “What can I add? What has not been said

I often try to imagine how the world might have felt in former times. To do this I first go back to my own younger days and try to get back inside some of those mentalities. How the world seems is obviously not to be separated from one’s own psychological stage in life. To a child, so many things are unknown and mysterious. With time many of the mysteries begin to recede and by mid-life routine has bleared and smeared so many things. The days move forward in lock-step. Some of this has to do with just being older, but also because the world has become so very rationalized. All those systems and grids and inescapable repetitions.

I’m trying here to get to another slant on these events, these serendipities. Maybe they resonate because they’re anomalies, because they stand out. Surprise crossings and echoings, little twinges that let us imagine a way of things outside the tyranny of patterns — reminding us, figuratively speaking, of a world as glimpsed by Dutch sailors.

Losing and finding, especially the unconscious associations that bring me what I didn’t know I wanted, but then see that I do indeed.

I want to zero in on the kind of finding that pertains to writing. In my view, writing is not a matter of remembering what had been forgotten — though at some level it’s that, too — but of accessing the words and idea-linkages we want. Do we, when we’re writing, reach in to get the parts of our next sentence, or are they “given” to us? It so often feels like the latter, like being gifted, which naturally makes me wonder through what agency.

~

Improvisation gives us another angle. In jazz, we know, it’s the art of responsiveness, of simultaneous engagement both with the music and with the improvisatory moves of the other musicians. It’s having faith in your chops — a kind of “stupid” confidence that it will all come out right — and it’s a creative willingness. I think of one of my favorite quotes, that I kept pinned up over various writing desks in my younger years, Rene Crevel’s line: “No daring is fatal.” Obviously many acts of daring are just that — fatal — but I always thought of it in terms of artistic venturing.

Years and years ago, long before coming to Boston, I lived for some seasons in an ocean-side town in southern Maine called Biddeford Pool. I walked the beautiful beach and the shoreline daily. There was an area, hundreds of yards long, that was a vast jumble of rocks and tidal pools, and at low-tide it presented a fabulous obstacle course. It was not long before I had devised for myself a ritual that I thought of as Zen-like. I would start at one end — barefoot — and walk as fast I could across the expanse. I was not allowed to think a path, I had to trust that my feet would find the right way and avoid getting gashes. Mostly it worked — I was like a tightrope walker, teetering, exhilarated. I felt I had learned something profound. And I had.

I was at that time also quite enamored with the idea of bricolage. I think it hailed from Levi-Strauss. Bricolage was, as I put it to myself, the art of making do with what was to hand. Life-improvisation — a hugely attractive notion for me.

~

We are in New York, visiting, and yesterday we decided that we would walk the length of the High Line, from 34th to 12th. My brother-in-law has a bad leg, but was determined, and though it took us three times longer than it otherwise might have, we made it. I had plenty of time to look at skyscrapers and backs of old buildings — brickwork and steel and lots of crazily reflecting glass all around — and so I had the iPhone out and was snapping at a high rate. Everything seemed a likely subject.

I remembered what Walter Benjamin wrote: “Every day the urge grows stronger to take hold of the world by way of the image.” If the urge was strong back then, it is now a collective obsession. Not only was I succumbing, but so was everyone else. I looked around me and saw, as in a dream, hundreds of people doing what I was doing. Of course, I wanted to somehow be a special case, so I told myself that by thinking about it, critiquing the practice even as I continued practicing, I was exempting myself. But we know that’s not how it works.

What is this picture-taking all about? Clearly it’s different things to different people. The couples taking selfies against the skyline are doing one thing, the tourists taking evidence to bring home and show friends another, and then there are those who are looking for what might end up as an artful image?

There is another kind of answer in Don DeLillo’s White Noise, the passage where one of the characters, a self-styled culture theorist named Murray, talks about a particular barn advertised as “the most photographed barn in America.” People gather from far and wide with their cameras and Murray, watching them looking, reflects. There are, for me, two take away ideas in his spiel. One is his remarking on the tautology of something being famous for being famous — and that peoples’ picture taking is a form of participation in a collective supposition.

The other is Murray’s assertion that: “Once you've seen the signs about the barn, it becomes impossible to see the barn.” And — implicitly — once all those pictures have been taken, the reality of the thing has been leached away.

This last notion is akin to stories of Rain Forest tribesmen who refused to have their photographs taken because they were afraid their souls would be stolen.

When we got home after the drive from New York, we wanted to watch a movie and picked something a friend had recommended called The Lincoln Lawyer. An L.A. based legal thriller — just the thing. I’ll just zoom in on a single moment. The lawyer, played by Matthew McConaughey, is at one of those dead-end points in his case. Weary, hungover, he’s studying photographs of the crime victim. He’s in the zone of that stupidity we keep invoking. He’s just staring and staring. You can feel the tension build, and then comes the breakthrough. Looking has turned into seeing. The tiniest anomaly has caught his eye. He is the L.A. noir version of Dupin. His subtle double-take, at the merest flicker of the eyelids, has a more satisfying drama for me than any car-chase or shoot-‘em-up.

~

The whole discussion of literature, at least in academia, is predicated on what might be called the “missionary position” of reading. A book or text is engaged from its beginning and tracked through to conclusion, chapters being the mile-markers.

But in my experience, most reading happens otherwise, and is influenced at every turn by variables in mood. Where are you inwardly stationed as you turn the pages? Now that we are fully enrolled in the digital way of things, most of the day’s reading is, inescapably, a grasshoppering from here to there, and sometimes back again. But even before the digital, long before, I knew that most of my reading was unstable. The beam of focus was moving all over — glancing ahead, winding back, re-reading passages, etc. It’s worse now. Staying the course — taking in one sentence after another, from page 1 to the end — that’s the welcome anomaly, and when it happens I want to cry out some variant of “Look Ma, no hands!”

What I’m really interested in here is the permeability between book and reader, the transactional nature of reading, at least the kind we tend to do. A book can powerfully influence the reader’s mind-state — mood — just as that reader’s mood is a kind of scrim through which the contents of the book pass, and which determines so much about the reception.

A mutuality, a passing back and forth of influence. This got me thinking about divination, that species of which was once called the Sortes Vergiliana. The person (Latin speaker, of course) seeking guidance in some vital life-business, would open his Virgil blindly and point. The lines he landed on became the tea leaves, the Rohrsach, the interpretable direction indicator of the future — along with practices like “reading” the entrails of an animal, or the flight patterns of birds, or, I suppose, the crenellations formed when a melted lump of lead is thrust into cold water. Of course, it need not be Virgil. Many have used the Bible in just such a way.

I have a memory of being twenty and, besotted with Henry Miller’s The Tropic of Cancer, playing the game (half-seriously, as any game gets played) asking at some moment of confusion “What would Henry do?” Finger would be plunked down on the randomly opened book. I venture to say that the finger was all but certain to land on some bit of erotic braggadocio, and I don’t think any of those prophecies were fulfilled. But the game absorbed me, as did the divinatory supposition that underlay it.

~

I return again to the losing and finding question. Cortazar’s Hopscotch is a case in point. The mood of the book stays vivid for me, but I can recall very few of the episodes. This is true, for me, of so many books I don’t even want to start to count. I get so frustrated. Something once had is lost, and trying to bring it back feels hopeless. At the same time, though, there is the feeling that the stuff is in there — in my mind — somewhere. That the contents have been deleted but not erased altogether. Which is maybe what is meant by the variously attributed adage that “Culture is what remains when you have forgotten everything you have read.”

I’m interested in re-reading for obvious connected reasons. There are probably as many experiences of re-reading as there are kinds of reading. You can go back to a book and discover that you recall absolutely nothing — there are no sparks of recognition whatsoever. You might also discover, reading along, that it all starts coming back, like an undeveloped photograph immersed in a chemical bath. Or — another possibility — what is often my experience: that bits and pieces come back episodically, likely underscoring where our keenest attention had once been directed.

And there is also the “that was then, this is now” effect, where a book we think we know quite well seems quite different from what we thought we remembered. This is obviously because we ourselves have changed, have come to understand more of the human heart, or become more jaded, less caught up by once-admired flourishes.

With a novel, the text is often a mnemonic to help us recover the text we had forgotten. The action of recovery can make the reading act more profound, for we are not only reading the writer’s sentences; we are also participating in a connecting again with something that seemed to have fallen out of memory.

The one thing I would add here, maybe the main thing, is that this is a process that happens by way of language. Having a book come back to you is not to be likened to the ordinary retrieval of some memory from the past. Language, as all writers and readers know, is the expression and intensification of consciousness. To be lost in a book is not the same as being lost in a city, or a dark wood. And finding the way is different, too. It can feel like the restoration of power when a broken circuit is repaired.

~

Years and years ago, when I was first cutting my teeth writing reviews and criticism, I had, as we all do, my pantheon of honored exemplars — Cyril Connolly, Randall Jarrell, Guy Davenport, Sontag, and George Steiner to name just a few. So you can imagine how psyched I was when I saw that Steiner was going to give a talk at the Boston Public Library. I’m pretty sure that was the venue.

Anyway, I went and heeded and was made dizzy by the referential outlay. In those days no one could make me feel like more of an intellectual dolt. Steiner had that way of writing things like: “Of course so much of so-and-so’s thinking is beholden first to Heidegger, but then also to the early phenomenologists — “ and that’s just the first half of a sentence I conjure up as studded with allusions and presumptions of an inside knowledge.

I forget the topic of that day’s talk, but I do remember standing on the street afterward trying to get my legs back under me. I was trying at the same time to hail a taxi to get me back to Cambridge. Leaning out from the curb, I noticed a diminutive figure taking the same posture, and with so much lead-up you already know that it was the critic himself. I turned and told him how much I’d enjoyed his talk, and he asked where I was headed. “Harvard Square,” I said. He was too, he said, and asked me if I wanted to share a cab. Well…

So there we both were in the back seat of as Boston taxi that was making it way slowly through rush-hour traffic. I knew Steiner’s work well enough to ask him good questions — not because I wanted answers, but so that I could show myself off as a serious reader of his work. He liked that, and as we inched along, I felt him start to relax from giving lightning rejoinders.

Then, at one point, he began to talk more personally. I remember just where we were, coming up Memorial Drive with Harvard walls on our right. How he got to this next confidence I can’t reconstruct, but right at that spot he did turn to me and said, basically, that he’d been playing this intellectual sport all his life; that he’d finally reached the age when he had to get serious. Serious? I’m sure I showed my surprise. Who could be more serious than George Steiner, for God’s sake? We were nearing the end of our ride and there was only enough time for him to start an answer. He said — quite pointedly — that he was ready at last to find out what his life of reading and study — the philosophy, linguistics, classic literature, etc. — was good for. He needed to know if there was, in him, a ground for faith in something. And if there was, then he had to act on that.

That was it. We had arrived at Out of Town News. Steiner generously paid the fare, and we went our separate ways. I was left feeling disconcertingly curious. I had caught hold of a fragment, nothing more.

I’ve found since turning 65 — somehow a big marker number — that the memory of that cab ride keeps coming back to me. It’s no mystery why. I’m harkening to a similar impulse, I know I am. Following Kierkegaard’s maxim: “Purity of heart is to will one thing” — I want to find what that one thing is.

~

The memory of my best writing moments haunts, most grievously when the desire is there but the impulse is absent, or when the impulse flickers and sputters but doesn’t catch, when the words — which I believe are right there, as if on the other side of the sheerest membrane — will not come. Remembering the good runs is a kind of reproach. My younger self — it is always, necessarily, the younger self — mocks me. It’s not just writing at stake, but everything. The worth I felt when I worked, when I was young — even if that was only yesterday — is gone. This is now and henceforth the way of things; this is the new reality.

The thought is hardly original, I know that. But right now I’m thinking less about the drought, and more about how we experience inspiration when it does come.

The unexpected surges feel like a visitation — something not wholly generated by the lone self. The word “inspiration” — literally a drawing in of breath — says as much. I can only speak for myself here, but when I am able to enter that state, when it feels like the words are rushing through the gates, when combinations arrive that I would not necessarily think up in my daily state, I feel changed — not just at pencil point, but throughout

I mean — how to put this? — that certain exceptional moments at the desk are not just business as usual only with a finer fluency, but are, rather, changes of state. At these good moments, when the flow is on, I feel that I’m not just writing, I am also acting on — and changing — my private reality. My ruling planets have moved into a new configuration. I have affected my world in some way that goes beyond the page. I was not just ‘blessed,’ but was also repositioned, if briefly, with regard to the world around me.

This does relate to serendipity. The writing part, anyway. To be caught up in that flow feels like a continuous process of ‘coming upon,’ of finding. A phrase that suddenly appears in the mind makes me feel like there might be some other kind of pattern beyond the day’s ordinariness

~

Some days I do wake up and find an idea just waiting for me.

What I woke to today was the thought that when we are young and have our lives mainly still in front of us, we believe that life will lead us to the “answer,” that it’s there, waiting, like something wrapped under a tree. Probably we hold to that for a good long time — so long as we feel there is enough future in front of us to keep that notion active.

But something changes — it did for me, anyway — in late middle age. In moments of private reckoning, I begin to acknowledge that most of it is behind me now, and that the shaping experiences still to come will be, many of them, under the sign of loss. I’d had that feeling (thought) for some time. What came to me this morning was the realization that so far as life-meaning goes, it will most likely not be out there, wrapped and waiting. It will have to come — if it comes at all — from the exploration and contemplation of what has already been. Memory is what we have to work with. As Rilke wrote: “The work of the eyes is done. Go now and do the heart-work on the images imprisoned within you.”

The words point a direction, and in the pointing propose a destination, not just heart-work for its own sake, but heart-work in the service of transformation. I’m convinced that whatever challenges and rewards are still in store are going to be more inward than outward. The notion brings a kind of relief, even a certain excitement. Where is there to get to? — a shortened version of the Gauguin questions. But also: how to get there? The question of memory, maybe especially the involuntary memory, is highly relevant here.

~

My father — pictures of my father — are behind many of my thoughts lately. His death changed things. I have always pored over images of family members, his especially, but never as attentively as I did after he died. Working through multiple photo-albums, I would construct in my mind a kind of motion study of the man’s life from earliest childhood into old age. I was, at some level, taking him as a proxy.

Doing this while he was still alive, I started to note how changes of time and vantage completely change the looking. One instance: I’ve had a framed photograph of my parents standing together on my bookshelf for years and years. Pausing to look, I would always see him there as the grown man that he was. Until one day I did a double-take. It was the time I looked and realized he was younger than I was. In an eye-blink the content shifted, turned itself inside out, in a manner of speaking.

After my father died I also saw his likeness in a different way. My mother still lives in their apartment, and there are photographs (of him, or him and my mother) everywhere. Photographs that were in the very same place they were when I would make my weekly visits. The fact of his death has changed them all. Before they were merely potent, full of the idea of time passing. Now that he’s gone, it is as if they are, all of them, held in some fixative. They represent irreversibility — this was, and never again. So long as he was alive they were somehow still part of a work-in-progress. Benjamin in his essay on the storyteller, quotes Morris Heimann: “A man who dies at the age of thirty-five is at every point of his life a man who dies at the age of thirty-five.”

And now some sad news. I found out yesterday that Bill Corbett, a friend of some 35 years had died. We all knew he was living with an inoperable cancer, and the doctors had “given” him a few months to live. So it was not a bolt out of the blue. But the news of death is always that.

Here is a serendipity I will not theorize about.

I was driving from Arlington to Weston, where I had a one o’clock appointment with the man who does my mother’s taxes. Driving along 95, coming up on the Weston exit I suddenly found myself thinking about Bill. I hadn’t seen him for a while — he had gone into private seclusion a few months back. Now I was wondering how far the cancer had spread, allowing that it would probably not be long. Then I thought about the life he had lived — full of friends, open to great enthusiasms (art, jazz, poetry, wine…). The time was about 12:45, because I was checking the clock to make sure I was not running late for my appointment.

When I got to the parking lot, I took a quick look at my phone. And there it was, the e-mail from my friend Askold, with the subject line BILL. Askold wrote that Bill had died that morning. The time of the e-mail was 12:41. Askold the messenger (he was also the one who notified me of Liam Rector’s death). Still, it’s all strange. I heard of Seamus’ death via an e-mail from Peter Balakian. “Kill the messenger,” they say, but I’m not going to do that. Who would be left?

~

I’ve been trying to figure out how a person (me) who for decades has always had his nose in a book has changed, has arrived at a place where, when given time, he just thinks. I don’t mean purposeful pursuit of a subject, rather an idle brooding. At its best it might be a version of Flaubert’s ‘marinade’ — a word I like so much in this context, for it conveys that thinking does not always have to be active, but can also be receptive. In these pandemic days I can’t seem to give myself over to another’s narrative, or vision. I realize that I’m almost echoing my father here, his assertion — which I mocked for years — of “why should I read a book, I already have too much to think about?”

Most of my inner life now finds me installed in a great — and absorbing — passivity. A complete switch from my younger days when I was going after to this new state of seeing what comes to me. Where am I when I’m in Doctor Seuss’s “waiting place”? Good question. What am I doing? I’m processing memories, I’m noticing things and going off on tangents of reverie, which are in no way directed, but which do sometimes yield things I need to hurriedly note down. It’s all very much about finding.

Last week, I drove for hours on Route 9 East through the great state of Maine — hours and hours, as you well know, of almost uninterrupted forest — and the whole time I was tuned to this station I’ll call, for lack of a better word, “me.” The needle stayed on that dial for the next five days. In those long quiet hours between nightfall and the next day’s duties, I did more than once ask “should I read now?” But there was just no impulse.

I’m divided on whether to see this as laziness — the failure of some long-held resolve — or a necessary next step. It feels needed. The passivity feels full, loaded with possibilities. There is just the waiting.

~

And the looking — looking as what one does when in front of a painting, but also, not unrelated, as a kind of thinking. With a painting that looking is conditioned and guided. With undirected reverie, though, there is something else. Something closer to that idea of “the open” that Rilke kept returning to. But Rilke’s idea of the open is about what’s in front of us, the space we move into, and what I’m talking about also has to do with what’s behind.

A friend once sent me a quote from William Maxwell, from an essay called “Nearing Ninety,” in which he writes — it’s the last sentence — “Every now and then, in my waking moments, and especially when I am in the country, I stand and look hard at everything.” That stayed with me. It gets the feel of those moments, though who can say what is going on in Maxwell’s looking. He seems to be as far in the moment as he can get, taking things in knowing that they are not forever. He has discovered a heightened appetite for the world.

But other parts of the essay are backward-facing. Maxwell also writes, “I have liked remembering almost as much as I have liked living.”

~

Sven Birkerts was for many years the Director of the Bennington Writing Seminars. He has reviewed widely and is the author of ten books, including The Gutenberg Elegies and The Art of Time in Memoir. His new book, an appreciation of Nabokov's Speak, Memory will be out in December. He co-edits the journal AGNI at Boston University and lives in Arlington, MA.